"Where Do the Walls of Our House End?":

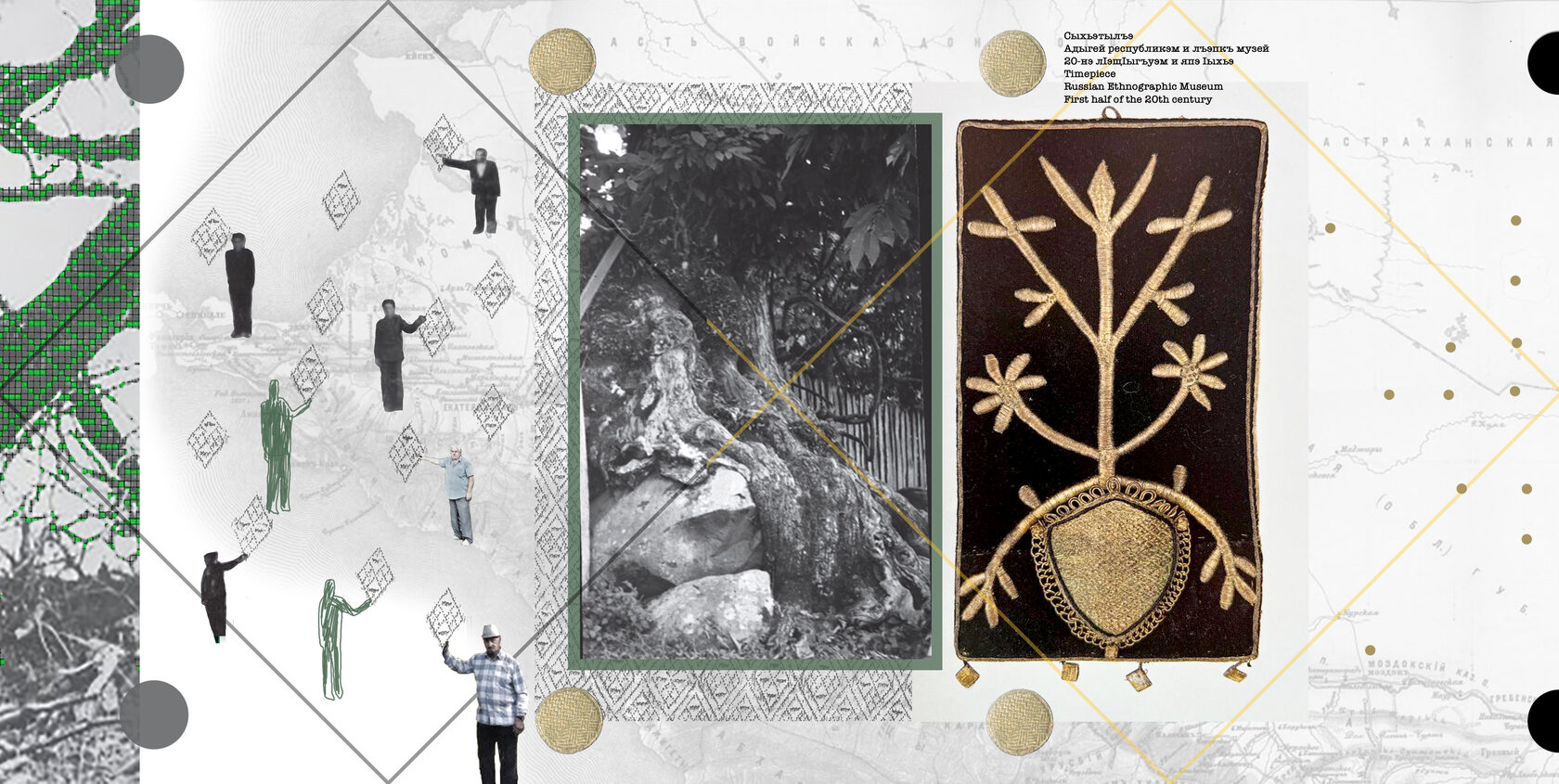

The Circassian Gardens as Memorial Structures

The Circassian Gardens as Memorial Structures

The Russo-Circassian War (1817-1864) entailed the annexation of North Caucasus to the territory of the Russian Empire. In addition, most of the Adyghe (Circassians) 1 were displaced due to a policy of genocide and forced resettlements.

During the eviction of the Circassians, thousands of people waited for months for ships to Turkey, dying on the shores of the Black Sea from exposure, hunger and disease. An eyewitness to the events, I. Drozdov, describes the horrific scenes in the aftermath of forced dispossession:

“A staggering sight presented itself to our eyes along the way: the scattered corpses of children, women and old people, torn to pieces, half eaten by dogs, settlers exhausted by hunger and disease, barely raising their legs from weakness, falling from exhaustion and still alive, they became prey for hungry dogs... The entire northwestern coast of the Black Sea was strewn with corpses and dying people, between which there were small oases of the barely alive, awaiting their turn to be sent to Turkey... Turkish skippers, out of greed, piled Circassians en masse onto ships and took them to the shores of Asia Minor, and, like cargo, they threw the extra ones overboard at the slightest sign of illness. The waves threw the corpses of these unfortunates onto the shores of Anatolia. Hardly half of those who went to Turkey arrived there. Such a disaster on such a scale has rarely befallen humanity...” [Drozdov, 1877].

The effects of this tragedy continue to haunt the present. To this day, many Circassians refuse to eat fish, given that fish fed on the bodies of their fellow countrymen who perished. Currently, most of the Adyghe ethnic community (according to various estimates, up to 80%) still live outside the territory of the Russian Federation: in Turkey, Syria, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, etc. — in more than 50 countries of the world. During the Soviet era, it was not possible for the Circassians to return to their historical homeland. Active repatriation has only been a phenomenon of the last three decades.

The genocide of the Circassians remains unrecognized by the Russian state — still numerous requests and petitions go unanswered. Activists called for a boycott of the XXII Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, due to the fact that much of the sports infrastructure was built on sites of genocide. In addition, the Olympic organizing committee ignored the history and culture of the indigenous population. On February 1st, 2014, a protest was held in Ankara with the participation of 1,200 people. Protestors sported placards with the inscriptions “The Sochi Olympics will not hide the genocide” and “Snow will not hide the blood of Krasnaya Polyana”.

The events of the Russo-Circassian War continue to be the cause of various “commemorative wars” in the country. There is a marked disjuncture between community memory of genocide and official memorial policy, championed by monuments to the various military leaders responsible for the genocide in the North Caucasus. Still, there are bans on mourning processions on the Day of Remembrance and Sorrow of the Circassians on May 21. Outside the North Caucasus, residents of other regions of Russia know almost nothing of the cultural trauma of the Russo-Circassian war. This history is largely ignored, silenced, censored or self-censored, which makes it challenging to work through these traumas and build processes of reconciliation. The mammoth task of coming to terms with these atrocities involves not forgetting (crimes against humanity cannot be overcome by oblivion), to avoid replacing or ameliorating it with a positive agenda. Rather, the recognition of the crimes committed is essential if the asymmetry of cultural memory is to be reckoned with. It remains a challenge to find ways to cope with the pain of collective trauma, to reduce the effect of “mnemalgia” and weaken the work of suffering in order to find resources for building images of a shared future. We must synchronize our past in order to co-exist in the present.

During the eviction of the Circassians, thousands of people waited for months for ships to Turkey, dying on the shores of the Black Sea from exposure, hunger and disease. An eyewitness to the events, I. Drozdov, describes the horrific scenes in the aftermath of forced dispossession:

“A staggering sight presented itself to our eyes along the way: the scattered corpses of children, women and old people, torn to pieces, half eaten by dogs, settlers exhausted by hunger and disease, barely raising their legs from weakness, falling from exhaustion and still alive, they became prey for hungry dogs... The entire northwestern coast of the Black Sea was strewn with corpses and dying people, between which there were small oases of the barely alive, awaiting their turn to be sent to Turkey... Turkish skippers, out of greed, piled Circassians en masse onto ships and took them to the shores of Asia Minor, and, like cargo, they threw the extra ones overboard at the slightest sign of illness. The waves threw the corpses of these unfortunates onto the shores of Anatolia. Hardly half of those who went to Turkey arrived there. Such a disaster on such a scale has rarely befallen humanity...” [Drozdov, 1877].

The effects of this tragedy continue to haunt the present. To this day, many Circassians refuse to eat fish, given that fish fed on the bodies of their fellow countrymen who perished. Currently, most of the Adyghe ethnic community (according to various estimates, up to 80%) still live outside the territory of the Russian Federation: in Turkey, Syria, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, etc. — in more than 50 countries of the world. During the Soviet era, it was not possible for the Circassians to return to their historical homeland. Active repatriation has only been a phenomenon of the last three decades.

The genocide of the Circassians remains unrecognized by the Russian state — still numerous requests and petitions go unanswered. Activists called for a boycott of the XXII Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, due to the fact that much of the sports infrastructure was built on sites of genocide. In addition, the Olympic organizing committee ignored the history and culture of the indigenous population. On February 1st, 2014, a protest was held in Ankara with the participation of 1,200 people. Protestors sported placards with the inscriptions “The Sochi Olympics will not hide the genocide” and “Snow will not hide the blood of Krasnaya Polyana”.

The events of the Russo-Circassian War continue to be the cause of various “commemorative wars” in the country. There is a marked disjuncture between community memory of genocide and official memorial policy, championed by monuments to the various military leaders responsible for the genocide in the North Caucasus. Still, there are bans on mourning processions on the Day of Remembrance and Sorrow of the Circassians on May 21. Outside the North Caucasus, residents of other regions of Russia know almost nothing of the cultural trauma of the Russo-Circassian war. This history is largely ignored, silenced, censored or self-censored, which makes it challenging to work through these traumas and build processes of reconciliation. The mammoth task of coming to terms with these atrocities involves not forgetting (crimes against humanity cannot be overcome by oblivion), to avoid replacing or ameliorating it with a positive agenda. Rather, the recognition of the crimes committed is essential if the asymmetry of cultural memory is to be reckoned with. It remains a challenge to find ways to cope with the pain of collective trauma, to reduce the effect of “mnemalgia” and weaken the work of suffering in order to find resources for building images of a shared future. We must synchronize our past in order to co-exist in the present.

1We will use the names Adygs/Adyghe (endoethnonym) and Circassians (exoethnonym), equally common and accepted among representatives of the ethnic community, as synonyms. The following ethnonyms are the names of individual ethnic groups of the Circassians: Adygeans (Abzakhs, Ademeys, Bzhedugs, Guaye, Yegeruqways, Zhaneys, Mamkheghs, Makhoshes, Natukhajs, Chemirgoys, Hatuqways, Khegayks, Khetuqs, Chebsins), Shapsugs, Kabardians, Besleneys, Ubykhs. At this moment, the Circassians in the Russian Federation predominantly live in three national subjects: the Republic of Adygea, the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic and the Karachay-Cherkess Republic.

*

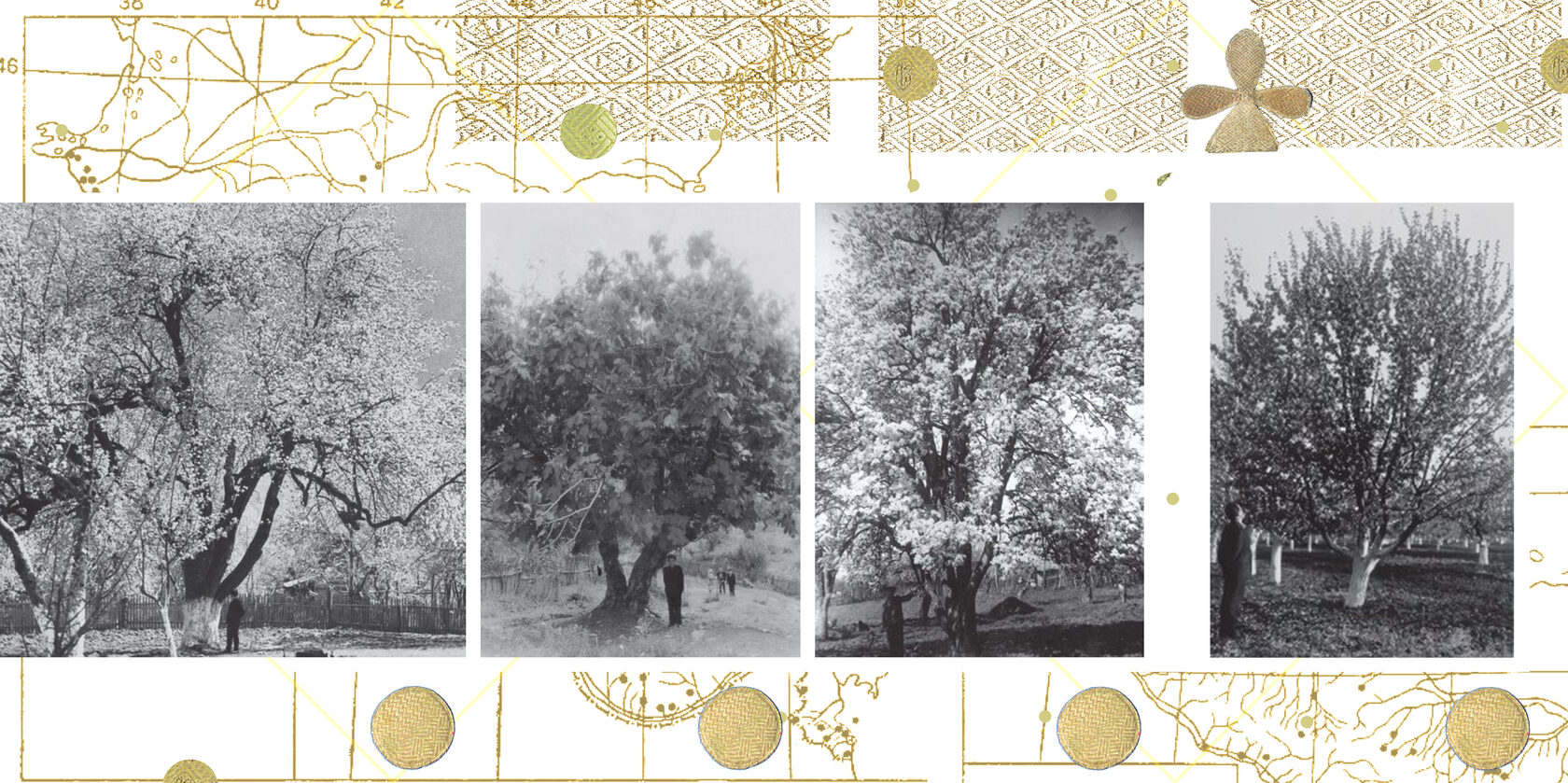

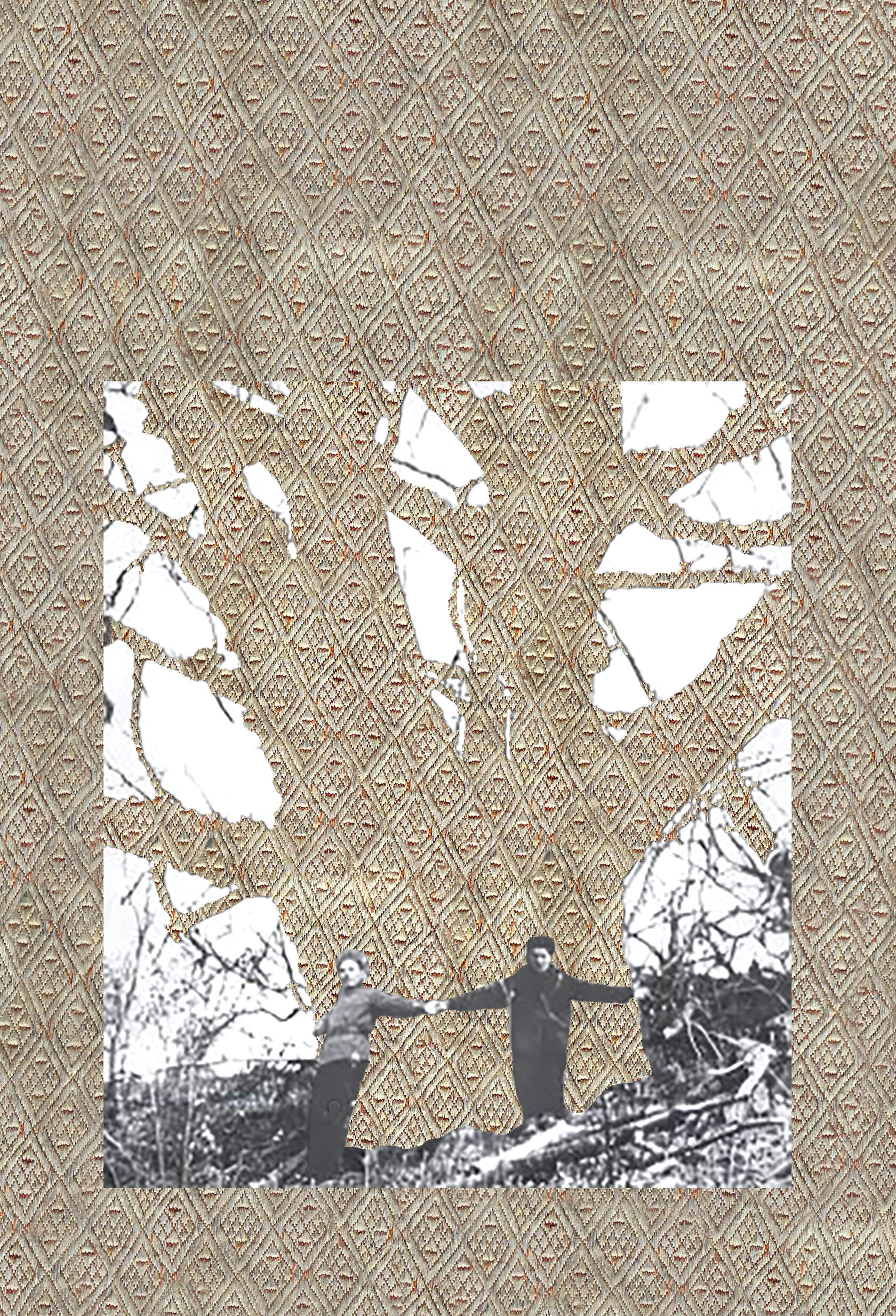

An immense number of trees in the Circassian gardens — unique natural and cultural monuments, as well as the sacred groves of the Circassians, have died over the past approximately 160 years. Still, some of the trees remain standing. They are silent witnesses to the tragedy, having survived both the Russo-Caucasian War and the years of Soviet power. If decisive measures are not taken to preserve them in the next few decades, these unique monuments of indigenous horticultural knowledge will perish. In this article, we propose considering the Circassian gardens from the perspective of a difficult heritage. That is, as organic “memorial structures” and relics of histories of deportation and the genocide of the Circassians by the Russian empire, followed by the the seizure and mastering of Circassian lands.

We will examine how “phyto-archeology” (a new discovery made by the horticultural heritage of the Circassians) evidences the colonization of the territories of the Black Sea and its coastline. We will also consider how horticultural goals and metaphors were rendered justification for deportation processes, in addition to how the processes of academization of Circassian indigenous horticultural knowledge took place during the years of Soviet rule. We will examine how the policy of “fruit eugenics” and “phyto-miscegenation” on the part of autochthonous cultivars was implemented in Soviet breeding strategies. Finally, we consider the Circassian gardens in their contemporary context, and reflect on the efforts by academics and horticulturalists to study and preserve them.

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, most of the historical record can be attributed to Russian travelers who bolstered the views of the colonialists and conquerors. From their reports and documents, addressed to the typical Russian reader and collated at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, we glean a mosaic of information regarding the colonization of the area. More specifically, there is a gradual shift in tone as one works one’s way through the documents, as they move from euphoria at the newly acquired wealth of the region to horror and despair as the scale and implications of the tragedy are reckoned with. The colonists neglected to recognize the value of the Circassian horticultural knowledge, viewing these knowledge systems as barbaric and unenlightened. It is ironic that the colonial horticultural projects failed at the first stages: the newly annexed territory remained sparsely populated, uninhabited and abandoned for decades.Russian intellectuals, Kulturträgers and scientists traipsed in astonishment across tens of kilometers of pillaged land, observing the remains of an almost destroyed civilization.

An immense number of trees in the Circassian gardens — unique natural and cultural monuments, as well as the sacred groves of the Circassians, have died over the past approximately 160 years. Still, some of the trees remain standing. They are silent witnesses to the tragedy, having survived both the Russo-Caucasian War and the years of Soviet power. If decisive measures are not taken to preserve them in the next few decades, these unique monuments of indigenous horticultural knowledge will perish. In this article, we propose considering the Circassian gardens from the perspective of a difficult heritage. That is, as organic “memorial structures” and relics of histories of deportation and the genocide of the Circassians by the Russian empire, followed by the the seizure and mastering of Circassian lands.

We will examine how “phyto-archeology” (a new discovery made by the horticultural heritage of the Circassians) evidences the colonization of the territories of the Black Sea and its coastline. We will also consider how horticultural goals and metaphors were rendered justification for deportation processes, in addition to how the processes of academization of Circassian indigenous horticultural knowledge took place during the years of Soviet rule. We will examine how the policy of “fruit eugenics” and “phyto-miscegenation” on the part of autochthonous cultivars was implemented in Soviet breeding strategies. Finally, we consider the Circassian gardens in their contemporary context, and reflect on the efforts by academics and horticulturalists to study and preserve them.

In the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, most of the historical record can be attributed to Russian travelers who bolstered the views of the colonialists and conquerors. From their reports and documents, addressed to the typical Russian reader and collated at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, we glean a mosaic of information regarding the colonization of the area. More specifically, there is a gradual shift in tone as one works one’s way through the documents, as they move from euphoria at the newly acquired wealth of the region to horror and despair as the scale and implications of the tragedy are reckoned with. The colonists neglected to recognize the value of the Circassian horticultural knowledge, viewing these knowledge systems as barbaric and unenlightened. It is ironic that the colonial horticultural projects failed at the first stages: the newly annexed territory remained sparsely populated, uninhabited and abandoned for decades.Russian intellectuals, Kulturträgers and scientists traipsed in astonishment across tens of kilometers of pillaged land, observing the remains of an almost destroyed civilization.

Cannonball in a Tree. Dendrocide

The Cutting of the Forest or The Wood-Felling (1855) is a novella by Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy. The novella describes the mass destruction of forest plantations, a common tactic deployed by Russian troops during the Russo-Caucasian War. This policy formed the basis of its destructive system. The forest, which provided the highlanders of the North Caucasus with shelter and the advantage of surprise, was a source of fear and danger for the Russian troops. Due to catastrophic losses, the Imperial authorities conceived the strategy of clearing parts of the forest and using a safe road through the trees to gain advantage over the Circassians and their land. The clearing was typically the width of twice the range of a rifle shot, that is 400-600 meters.

The soldiers blasted whole habitats with gunpowder or cut down the forest into logs (often with great difficulty and at the cost of their own lives). In fact, not a single felling was completed without casualty. Invariably, someone was crushed or maimed by falling trees. The Pshat sacred forest was completely decimated by the end of May, 1837. On June 1st, a Russian officer, N.V. Simanovsky wrote in his diary:

The soldiers blasted whole habitats with gunpowder or cut down the forest into logs (often with great difficulty and at the cost of their own lives). In fact, not a single felling was completed without casualty. Invariably, someone was crushed or maimed by falling trees. The Pshat sacred forest was completely decimated by the end of May, 1837. On June 1st, a Russian officer, N.V. Simanovsky wrote in his diary:

The lovely grove that used to be on the shores of the Black Sea has already been all cut down what a shame!. From the centuries-old trees and fragrant hazel only stumps remain, but even those will be dug up over time. The ax destroyed everything... I went to see a hundred-year-old oak tree, shot from the sea with cannonballs in two places during the landing of Russian troops in 1834. One cannonball pierced him right through, and the other remained in him” [Simanovsky, 1837].

The Adyghes managed to create a symbiosis of horticultural and natural landscapes. The Circassian landscape delighted foreign travelers with its picturesque atmosphere. In 1810, the English traveler and writer Edmund Daniel Clark visited the Cossacks on the right bank of the Kuban, where he admired the view of the Circassian left bank: “As morning dawned, we had a delightful prospect of a rich country upon the Circassian side, something like South Wales, or the finest part of Kent; pleasing hills, covered with wood; and fertile valleys, cultivated like gardens” [Clarke, 1811].

The horticultural traditions of the Circassians aroused admiration and surprise in travelers, undermining preconceived notions of a “culture of savages”:

The horticultural traditions of the Circassians aroused admiration and surprise in travelers, undermining preconceived notions of a “culture of savages”:

In truth, I was not more pleased than astonished, to see the high state of cultivation exhibited in such a remote country, a country inhabited by a people that we were led to believe had not yet emerged from barbarism... Instead of finding it a mountain desert inhabited by hordes of savages, it proved to be, for the most part, a succession of fertile valleys and cultivated hills [Spencer, 1838].

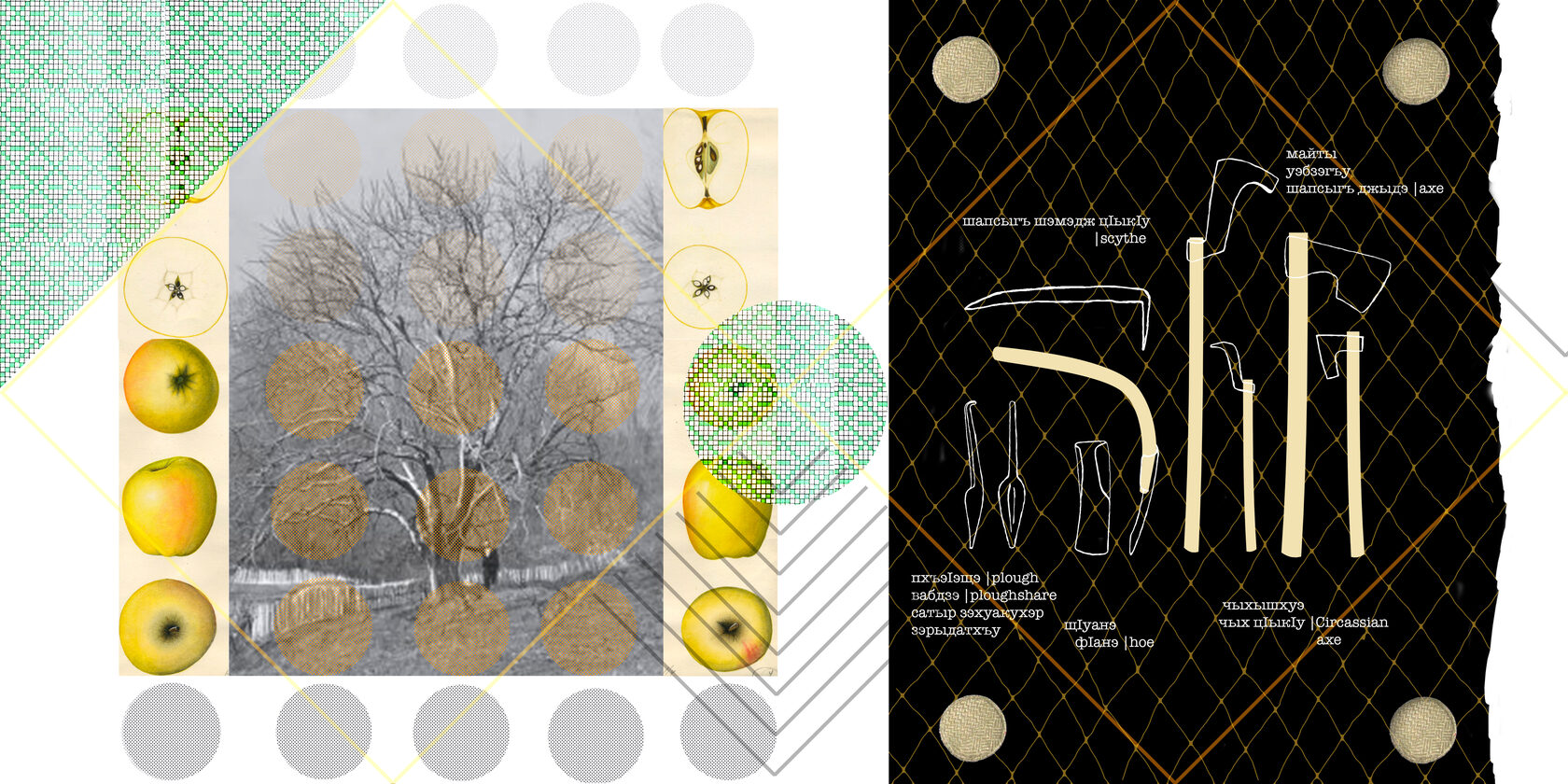

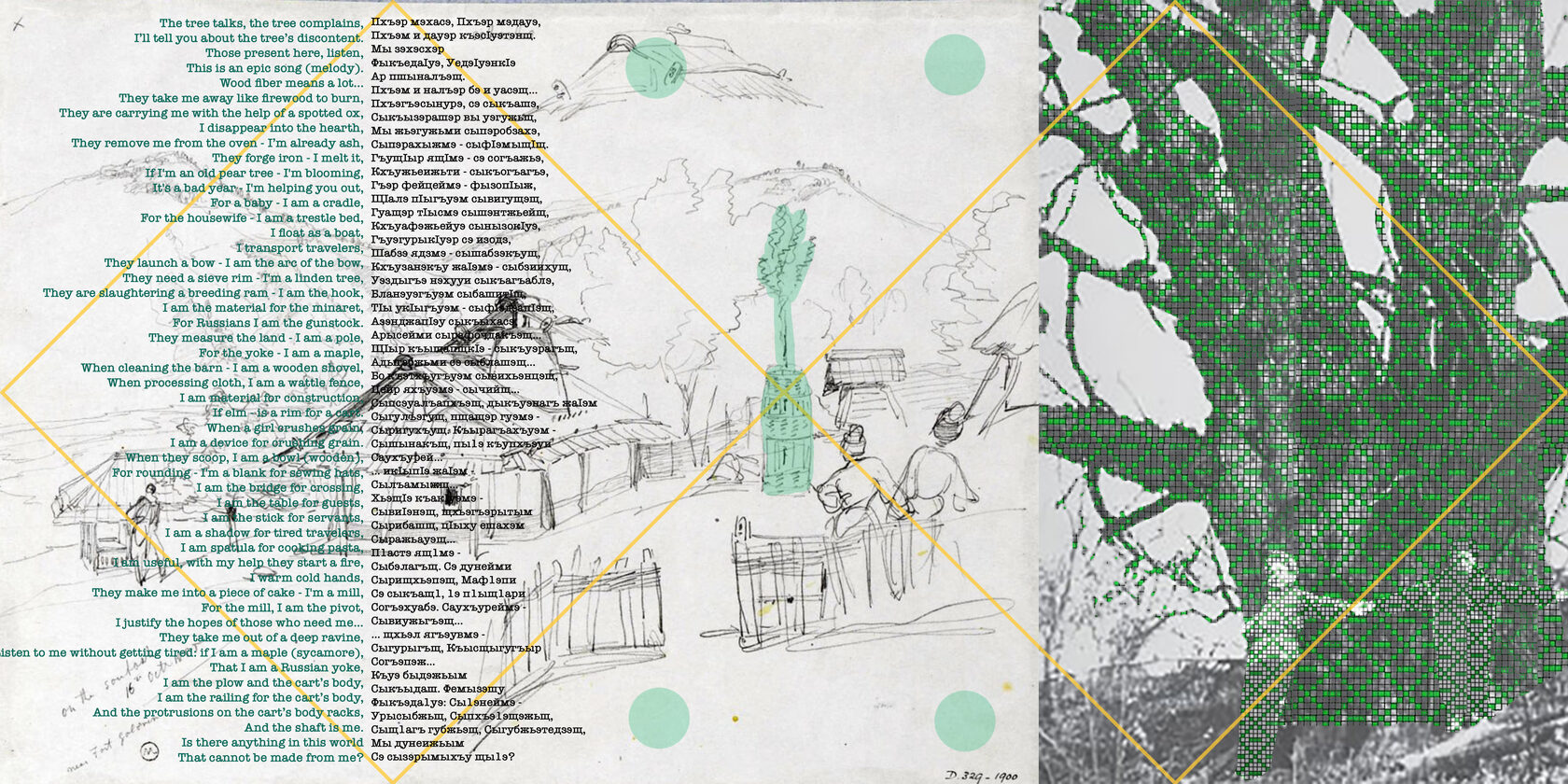

Circassian gardens (forest gardens) consist of fruit trees and shrubs scattered in the forests of the foothills and coastal areas of North-West Caucasus. A distinctive feature of Adyghe gardening was the cultivar structure. In the spring, when the graftage season began, the entire male population, including older men, shepherds and teenagers, carried sharp knives, binding and coating materials and scions of cultivated varieties of fruit trees with them for grafting. If they encountered wild trees, the trees were immediately grafted. According to legend, not a single girl married a young man who did not ennoble - did not graft - ten wild fruit trees with scions of cultivated varieties [Tkhagushev, 2008].

"Something Like South Wales": The Horticultural Landscape of the Circassians

The genocidal policy of eviction and genocide by the tsarist regime, sanctioned in official rhetoric, was justified and legitimized by the bogus claim that the Highlanders’ agricultural prowess was lacking. General R.A. Fadeev, for instance, was absolutely sure that “in relation to the production of national wealth, ten Russian peasants produce more than a hundred highlanders; it was much more profitable to populate the Kuban lands with our own peasants” [Fadeev, 1889]. Horticultural arguments and metaphor were decisive in the politics of genocide: “On the abandoned ashes of the condemned Circassian tribe, the great Russian tribe will rise... The tares are torn out, the wheat will sprout” [Ibid].

One of the most frequently repeated metaphors and comparisons to the highlanders was the image of a carnivorous predator: “The silent figure of a mountain rider, shaggy like a kite, predatory like a kite, prowling alone like a kite — so suits the whole bleak, wild situation of Daryal Gorge,” writes E. Markov, one of the ideologues of Russification, publicist and traveler [Markov, 1898]. In another text, he further develops his idea:

One of the most frequently repeated metaphors and comparisons to the highlanders was the image of a carnivorous predator: “The silent figure of a mountain rider, shaggy like a kite, predatory like a kite, prowling alone like a kite — so suits the whole bleak, wild situation of Daryal Gorge,” writes E. Markov, one of the ideologues of Russification, publicist and traveler [Markov, 1898]. In another text, he further develops his idea:

People stuck there, on their barren stones, thin, hungry, silent, tracking down rare prey with the vigilance and patience of hawks, cultivating in themselves for many years the instinct of a predator, the agility of a predator and the endurance of a predator [Markov, 1897].

The demonization of the highlanders, the description of them as “barbarians”, served the imperial Russian authorities as an ideological justification for their own punitive actions, the scale of which grew throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

The ruthless attitude towards the highlanders was justified by the belief in their economic and civil inferiority and the need to rationally use natural resources, which the “semi-savage peoples” of the Caucasus allegedly did not know how to use. Agricultural backwardness is evoked with horticultural metaphors that work to justify conquest: “Posterity will reap the fruits of the land watered with the blood of the brave, and will more than return to themselves the countless sums spent by their ancestors on this conquest” [Rosen, 1907].

The ruthless attitude towards the highlanders was justified by the belief in their economic and civil inferiority and the need to rationally use natural resources, which the “semi-savage peoples” of the Caucasus allegedly did not know how to use. Agricultural backwardness is evoked with horticultural metaphors that work to justify conquest: “Posterity will reap the fruits of the land watered with the blood of the brave, and will more than return to themselves the countless sums spent by their ancestors on this conquest” [Rosen, 1907].

"Fruits of The Land Watered With Blood": Horticultural Metaphors of War

The most common strategies of the Russo-Caucasian War, in addition to the direct homicide of the enemy and deforestation, were the displacement of the highlanders from those lands that could feed them, the destruction of crops, theft of livestock and the destruction of villages in case of resistance.

Counter admiral L.M. Serebryakov, who called the highlanders “herds of poor savages”, was well aware of the monstrosity and inhumanity embedded in the strategy of crop destruction and starvation, which he expressed a desire in resorting to in 1841: “... This measure, without a doubt, is so cruel, but the demands of military enterprises are not always compatible with pure philanthropy...”

[Serebryakov, 1865]. However, upper echelons of government did not support the ideas of the Counter admiral: the memories of events of the 1840, when starvation pushed the highlanders to a desperate offensive in which they captured and destroyed several fortifications on the Black Sea coastline, were still fresh. Subsequently, Serebryakov, managed to partially implement his plan. In October 1850, his squad marched through the lands of the Natukhajs and burned more than 2,000 households, along with huge reserves of grain. At the same time, about 200 highlanders were killed as they tried to resist.

M.I. Venyukov, who later became a famous ethnographer and writer in the early 1860s, commanded a battalion of the Stavropol Infantry Regiment. His writings provide eloquent accounts and evidence of the Circassian genocide and the agricide that accompanied it:

Counter admiral L.M. Serebryakov, who called the highlanders “herds of poor savages”, was well aware of the monstrosity and inhumanity embedded in the strategy of crop destruction and starvation, which he expressed a desire in resorting to in 1841: “... This measure, without a doubt, is so cruel, but the demands of military enterprises are not always compatible with pure philanthropy...”

[Serebryakov, 1865]. However, upper echelons of government did not support the ideas of the Counter admiral: the memories of events of the 1840, when starvation pushed the highlanders to a desperate offensive in which they captured and destroyed several fortifications on the Black Sea coastline, were still fresh. Subsequently, Serebryakov, managed to partially implement his plan. In October 1850, his squad marched through the lands of the Natukhajs and burned more than 2,000 households, along with huge reserves of grain. At the same time, about 200 highlanders were killed as they tried to resist.

M.I. Venyukov, who later became a famous ethnographer and writer in the early 1860s, commanded a battalion of the Stavropol Infantry Regiment. His writings provide eloquent accounts and evidence of the Circassian genocide and the agricide that accompanied it:

Mountain villages were burned out in the hundreds... crops were trampled by horses. The population of the villages, if it was possible to take it by surprise, was immediately taken under military escort to the nearest villages and from there sent to the shores of the Black Sea and further to Turkey... [Venyukov, 1878].

In his memoirs, written in Switzerland, he describes one of the operations to expel the highlanders:

The month of March [1862] was fatal for the Abzakhs of the right bank of the Belaya River, those very friends from whom we bought hay and chickens in January and February. The squad moved into the mountains along barely paved forest paths to burn villages. This was the most prominent, most “poetic” part of the Caucasian War. [Venyukov, 1878]

Ironically, Venyukov probably sympathized with the people he so mercilessly treated, given that he was living in Switzerland, outside the zone of censorship and persecution. At the same time, a representative of the intellectual elite considered the murder and expulsion of the highlanders, if unjust, then rational.

The Most "Poetic"”Part of the Caucasian War: Agricide as a Strategy

The initial hopes surrounding the conquest of the Caucasus were met with great enthusiasm.The new territories seemed like an earthly paradise, where one need not sow or reap. Everything was already established: gardens, fruits, precious trees and countless flowers. All one needs to do is harvest. One of the central ideologus of the Russo-Caucasian War, Fadeev, exclaimed:

The eastern coast with its extraordinary beauty is now part of Russia. The charm has been removed from him. The coastal strip now awaits, like an undeveloped mine, only people who would take advantage of its natural resources... This country will raise a breed of people that we have not heard of, even in fairy tales. We will see Russian highlanders. A chubby, blond Russian boy will take a visiting lady from the city on his horses along steep mountain paths to watch from a nearby peak how the sun rises from behind the snow [Fadeev, 1889].

The first travelers to the Caucasus described the newly annexed territory in vivid colors and terms. Fantasy coloured and packaged rumors in a magical veneer: this particular fantasy envisaged pleasure without labor or illness, an enchanted bliss without recourse to the conditions that made it possible. The new inhabitants of the region received a wealth of fresh harvests from the fruit trees planted in the gardens: these included apples, pears, cherries, cherry plums, plums, quinces, peaches, grapes, persimmons, apricots, mulberries, figs, walnuts, hazelnuts and chestnuts. Unprecedented excitement ensued in Moscow, because now, earthly paradise could be tasted.

In 1867, a correspondent for a Kerch newspaper wrote with great enthusiasm: “What pleasures await us, especially since these fruits, free from the costs of planting a garden and obtained at no cost, will be sold at a small and affordable price...” [Zametka, 1867]

***

In exactly twenty years the region was in a state of decline and desolation. Numerous speculators who had purchased prized lands would sell them at inflated prices. The forest would be barbarically felled and sold. The Circassian gardens would be destroyed or would gradually fall into disrepair. The peaches, discovered by the pioneers of Russian colonization, were becoming feral already in the second generation. Due to the lack of roads and the monopoly of shipping companies, it was no longer viable that these delicious fruits would even be transported from the territory, especially since they were perishable. Meanwhile, the Russian population forcibly resettled in the villages, suffered from hunger and poverty, without harvests and nor the slightest idea of how to practice horticulture in mountainous areas. Many would die of malaria. The once rich land would soon be described by travelers with a tone of hopelessness and profound disappointment, in stark contrast to initial descriptions. To convey this barren atmosphere, they used desert metaphors.

Too much time would pass before the colonialists discovered and described the indigenous, horticultural knowledge of the Circassians as legitimate. By the time this happened, everything would need to start over. But the Circassian gardens would survive.

In 1867, a correspondent for a Kerch newspaper wrote with great enthusiasm: “What pleasures await us, especially since these fruits, free from the costs of planting a garden and obtained at no cost, will be sold at a small and affordable price...” [Zametka, 1867]

***

In exactly twenty years the region was in a state of decline and desolation. Numerous speculators who had purchased prized lands would sell them at inflated prices. The forest would be barbarically felled and sold. The Circassian gardens would be destroyed or would gradually fall into disrepair. The peaches, discovered by the pioneers of Russian colonization, were becoming feral already in the second generation. Due to the lack of roads and the monopoly of shipping companies, it was no longer viable that these delicious fruits would even be transported from the territory, especially since they were perishable. Meanwhile, the Russian population forcibly resettled in the villages, suffered from hunger and poverty, without harvests and nor the slightest idea of how to practice horticulture in mountainous areas. Many would die of malaria. The once rich land would soon be described by travelers with a tone of hopelessness and profound disappointment, in stark contrast to initial descriptions. To convey this barren atmosphere, they used desert metaphors.

Too much time would pass before the colonialists discovered and described the indigenous, horticultural knowledge of the Circassians as legitimate. By the time this happened, everything would need to start over. But the Circassian gardens would survive.

"The Removed Charm": Eden Given for Free”

The first settlers appeared in the newly conquered territories in 1864. The Kuban Cossacks chosen by lot were added to the volunteer Cossacks, who formed the Shapsug foot coastal battalion of the Kuban army. 629 families totaling 4,157 people were accommodated in 12 villages. Like the Circassians, forced to migrate to Turkey or resettled on the plains, the Cossacks found themselves in the same situation of forced displacement: “They looked with longing at the mountains surrounding them and only dreamed of returning home” [Klingen, 1897]. Many of these settlers died from disease and starvation. In the first year, 463 people died, in the next 361 [Krivenko, 1893]. Residents of the Velyaminovskaya village settled in the lowlands in swampy areas and died from fever caused by malaria, dropsy and typhus: if in 1864 590 people lived in the village, then after 2 years, only 340 remained alive [Khatisov, 1867].

Residents of the villages faced crop failure. The problem was in part that most of the villages were initially established as a military settlement and the logic of their placement depended on the need to conduct military operations, which did not always correspond to the needs of agriculture. The second important problem was the Cossacks’ ignorance of farming methods in mountainous areas. Often the Cossacks had no motivation to cultivate the land. At the beginning of resettlement, the existence of villages was supported by monetary subsidies, and later by ready-made government provisions and food supplies.

Historian and archaeologist Praskovya Uvarova emotionally described the situation of complete impoverishment in which the new inhabitants of the region found themselves 25 years after the full-scale seizure of the territory:

Residents of the villages faced crop failure. The problem was in part that most of the villages were initially established as a military settlement and the logic of their placement depended on the need to conduct military operations, which did not always correspond to the needs of agriculture. The second important problem was the Cossacks’ ignorance of farming methods in mountainous areas. Often the Cossacks had no motivation to cultivate the land. At the beginning of resettlement, the existence of villages was supported by monetary subsidies, and later by ready-made government provisions and food supplies.

Historian and archaeologist Praskovya Uvarova emotionally described the situation of complete impoverishment in which the new inhabitants of the region found themselves 25 years after the full-scale seizure of the territory:

The region was conquered, the Circassians were evicted and the new settlers — Ukraininas, Cossacks, Greeks — abandoned the fields, destroyed the orchards, cut down the forests, and, despite the fertile land, they walk around just as poor, naked, and inconspicuous as in the North [of Russia]... [Uvarova, 1891].

Aware that the Circassians consistently produced rich harvests and even engaged in trade, the authorities encouraged the newly arrived settlers to cultivate the land and develop agriculture. However, the settlers, lacking motivation, devised a clever ruse: they planted roasted seeds, intending to convince the authorities that the soil was infertile.

Settlers

Sources show a fundamental difference between the colonizers and the highlanders, who were able to restore farming systems in a very short time. Noting the horticultural failure of the Cossack settlers, the lands were first offered to fellow believers, the Armenians and Greeks who fled from the Ottoman Empire, after which the commander of the troops of the Kuban region, Count Sumarokov-Elston, proposed settling Circassian families in Cossack villages to teach horticultural skills. Lieutenant General V. A. Geiman, who headed a large military formation in the last years of the war, proposed learning from the Circassians,. He also led the 1866 commission appointed by the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Army, to determine the causes of the disastrous state of the mountain Cossack villages of the Kuban region. The commission came to the conclusion that it was necessary to settle Circassian families in the mountain villages, who could in turn pass on their experience of working the land.

These measures did not help and ultimately, the villages of the Shapsug battalion were completely disbanded in 1868.

***

As the Russian botanist and soil scientist A.N. Krasnov wrote, “no matter how much they [the Cossacks] fought over the cursed land, it flatly refused to feed the alien newcomers, and the impoverished peasants scattered wherever they wanted, the same land to this day seems to be worthless, abandoned and overgrown fern” [Krasnov, 1895].

To understand this “curse of the land” and the reasons for the failures, numerous “bioprospectors” flocked to the Black Sea coast, including agronomists, pomologists, and horticultural technicians. Unlike the Western colonial powers, for whom bioprospecting was the first order of business when it came to exploiting new lands, Russian scientists and academics neglected the specifics of the local conditions of the newly annexed territories till the end, probably believing that the Empire, expanding its territory, would easily clone and reproduce itself. What they discovered was that the indigenous horticultural knowledge of the Circassians would unexpectedly force them to reconsider their attitude towards this culture.

These measures did not help and ultimately, the villages of the Shapsug battalion were completely disbanded in 1868.

***

As the Russian botanist and soil scientist A.N. Krasnov wrote, “no matter how much they [the Cossacks] fought over the cursed land, it flatly refused to feed the alien newcomers, and the impoverished peasants scattered wherever they wanted, the same land to this day seems to be worthless, abandoned and overgrown fern” [Krasnov, 1895].

To understand this “curse of the land” and the reasons for the failures, numerous “bioprospectors” flocked to the Black Sea coast, including agronomists, pomologists, and horticultural technicians. Unlike the Western colonial powers, for whom bioprospecting was the first order of business when it came to exploiting new lands, Russian scientists and academics neglected the specifics of the local conditions of the newly annexed territories till the end, probably believing that the Empire, expanding its territory, would easily clone and reproduce itself. What they discovered was that the indigenous horticultural knowledge of the Circassians would unexpectedly force them to reconsider their attitude towards this culture.

Cursed Land

Russian explorers and settlers had the opportunity to acquaint themselves with the ruins of the highlanders' culture. The former Circassian villages had become largely impenetrable, thicketed and overgrown with weeds, ferns, thorny bushes, climbing and creeping plants along with their gardens and arable lands. “Agri-archaeologists” who visited these ruins observed the state of arable land, gardens, as well as the construction of premises for domestic animals and food warehouses. For instance, the agronomist I. Serebryakov carefully described the structure of the Circassian plow, ard, crushes (for crushing gomi and millet) and hand mills. [Serebryakov, 1867]. At the site of village remains, Countess Uvarova found “entire reserves of the most delicious honey, preserved in huge bottles filled with wax” [Uvarova, 1891].

Based on still fragmentary information, the agronomist Klingen, like many other specialists in the field of agriculture, began to collect data on indigenous agricultural knowledge. With much indignation, he complained that certain agronomists took a one-sided approach to analyzing the methods of farming among the Circassians: they treated the Circassians with contempt calling them “wild barbarians, from whom, in their opinion, there was nothing to learn.... Someone, who could not study mountain farming, who did not want or could not turn into a real highlander, had to die of hunger or say goodbye to this country forever” [Klingen, 1897].

Russian researchers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries identified key mistakes on the part of the settlers that led to failures in the field of horticulture. The Cossacks used deep plowing, resulting in the grain rotting in the ground, while the highlanders used shallow plowing. The Cossacks plowed on the swampy plains while the highlanders worked the dry and sun-drenched slopes of the mountains. The Cossacks chose the wrong sowing time and also ignored seeds and cultivars adapted to local climatic conditions. The Cossacks were accustomed to a method of farming on the plain that was completely unsuitable in mountainous conditions due to the different climate and geological landscape.

As research continued, scientist began to outwardly recognize the existence of a special agricultural Circassian knowledge, and continued to emphasize the need to study it:

Based on still fragmentary information, the agronomist Klingen, like many other specialists in the field of agriculture, began to collect data on indigenous agricultural knowledge. With much indignation, he complained that certain agronomists took a one-sided approach to analyzing the methods of farming among the Circassians: they treated the Circassians with contempt calling them “wild barbarians, from whom, in their opinion, there was nothing to learn.... Someone, who could not study mountain farming, who did not want or could not turn into a real highlander, had to die of hunger or say goodbye to this country forever” [Klingen, 1897].

Russian researchers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries identified key mistakes on the part of the settlers that led to failures in the field of horticulture. The Cossacks used deep plowing, resulting in the grain rotting in the ground, while the highlanders used shallow plowing. The Cossacks plowed on the swampy plains while the highlanders worked the dry and sun-drenched slopes of the mountains. The Cossacks chose the wrong sowing time and also ignored seeds and cultivars adapted to local climatic conditions. The Cossacks were accustomed to a method of farming on the plain that was completely unsuitable in mountainous conditions due to the different climate and geological landscape.

As research continued, scientist began to outwardly recognize the existence of a special agricultural Circassian knowledge, and continued to emphasize the need to study it:

Seduced by benefits, the Cossacks came here from their wide steppes, with the hope of a good future; they took with them all their household belongings, all the tools for cultivating the land, all the habits and techniques of steppe farming — and they found mountains and clearings located not in the plains, but on the slopes of the mountains. They did not appreciate these meadows and gardens developed by the former native population, did not take advantage of their previous labors and, instead of continuing the work they had started and developing it, they began to fight nature, thinking with persistence to change its laws... Meanwhile, the abandoned village arable lands and gardens became overgrown thorns, blackberries and other thorny bushes, which are now more difficult to combat than before. Now we have to start all over again [Kuznetsov, 1890].

Phyto-Archeology: "Discovery"”of Indigenous Knowledge of the Circassians

Unable to yield their own bountiful harvests due to unsound horticultural practices, the settlers instead collected and sold large quantities of nuts and fruits from existing Circassian orchards, of which there was no shortage: “How much wealth there is every year! Huge spaces are littered with a thick layer of large sweet pears, sweet and sour Circassian apples cover the black, rich earth of the village like a red tablecloth!” [Grebnitsky, 1908].

The fruits were consumed both as fresh and also sold or bartered dried. The sale of fruits from these existing orchards was the only source of income for Russian settlers for quite some time. However, it was almost impossible to export fruits outside the region, especially perishable cultivars, due to logistical problems: the lack of maintained roads and the high cost of shipping transportation due to the lack of competition in the logistics market.

The methods of obtaining fruits in Circassian gardens were completely barbaric. Settlers cut down not only branches, but entire trees. Steps were cut out of the tree trunks so that settlers could more readily collect harvest. Massive deforestation was carried out by the Greeks, who were engaged in the cultivation of tobacco crops. In order to remove two or three crops of tobacco, theyuprooted Circassian gardens, because below them was the best soil for sowing tobacco. Another use of wood cutting was for burning coals, which was sold in wealthy villages or exchanged for bread.

The cutting down of tkhacheg, sacred forests, had catastrophic consequences. It led to the almost complete loss of the sacred landscape. Contemporaneously, in Adygea, unlike in Abkhazia, there is practically no national operating sanctuary left, and there are very few sacred trees left in active social practice.

While the Kuban population, placed in impossible conditions by the authorities, was living in poverty and dying from malaria and starvation, increasingly resorting to thoughtless extractivism, the Caucasian gardens were neglected and increasingly unsuitable for farming. There was no continuity between the high level of Circassian horticulture and settler farming practices.Only from the mid-1870s did the settlers begin to care for the trees planted by the Circassians and propagate these cultivars by grafting scions on wild trees.

The fruits were consumed both as fresh and also sold or bartered dried. The sale of fruits from these existing orchards was the only source of income for Russian settlers for quite some time. However, it was almost impossible to export fruits outside the region, especially perishable cultivars, due to logistical problems: the lack of maintained roads and the high cost of shipping transportation due to the lack of competition in the logistics market.

The methods of obtaining fruits in Circassian gardens were completely barbaric. Settlers cut down not only branches, but entire trees. Steps were cut out of the tree trunks so that settlers could more readily collect harvest. Massive deforestation was carried out by the Greeks, who were engaged in the cultivation of tobacco crops. In order to remove two or three crops of tobacco, theyuprooted Circassian gardens, because below them was the best soil for sowing tobacco. Another use of wood cutting was for burning coals, which was sold in wealthy villages or exchanged for bread.

The cutting down of tkhacheg, sacred forests, had catastrophic consequences. It led to the almost complete loss of the sacred landscape. Contemporaneously, in Adygea, unlike in Abkhazia, there is practically no national operating sanctuary left, and there are very few sacred trees left in active social practice.

While the Kuban population, placed in impossible conditions by the authorities, was living in poverty and dying from malaria and starvation, increasingly resorting to thoughtless extractivism, the Caucasian gardens were neglected and increasingly unsuitable for farming. There was no continuity between the high level of Circassian horticulture and settler farming practices.Only from the mid-1870s did the settlers begin to care for the trees planted by the Circassians and propagate these cultivars by grafting scions on wild trees.

Destruction of Circassian Gardens

After conducting a comprehensive survey of the Circassian coast, agronomist I.N. Klingen, in a rather bureaucratic report, includes a phrase completely atypical for this kind of document. It communicates deep dispiritedness: “The whole fate of the Russian colonization of the eastern coast turned out to be so sad and strange... It is difficult to imagine a more striking failure...” [Klingen, 1897]. He draws a disappointing conclusion. The entire eastern coast of the Black Sea and most of the Batumi district are

a vast desert with a population rarer than Siberia... The highlanders disappeared, but along with them their knowledge of local conditions, their experience, that folk wisdom disappeared, which is the best treasure of the poorest peoples and which even the most cultured European should not disdain... Russian power has used sixty years to conquer this country for us, at the cost of incredible suffering, through the efforts of unheard-of heroism. Hundreds of millions of rubles have been spent, hundreds of thousands of people’s lives have been ruined, and now this country must be taken again in battle... The song of triumphant nature sounds loudly, finally drowning out the pathetic babble of pathetic colonization.

If in 1886 only 10,177 people lived in 51 settlements of the Kuban Region, then at the time of 1913 the population still remained small with only 179,796 people [Kuban, 1914].

"Pathetic Babble of Pathetic Colonization": "A Vast Desert With a Population Rarer Than Siberia"”

In 1884, an article titled “Main Acquisitions” by publicist E.L. Markov was published in the pages of the Rus’ newspaper. It gave an intermediate summary of the colonial conquests of the Russian Empire throughout the course of the nineteenth century:

First, Fort Perovsk, then Tashkent, Khiva, Bukhara, Fergana, then Ahal-Teke and, finally, Merv. Step by step, imperceptibly, somehow fatally, as if involuntarily pulled us away from ourselves... It would be time to open our eyes to the light with which the world is enlightened, to live in communion with the peoples who have managed to develop high art, deep knowledge, subtle community life during these sad centuries of war and disorder... We will be eternal debtors, eternal bankruptcies both in the moral and economic sense, until we leave others alone and finally take care of ourselves. There must be a limit to everything, to patience and indiscretion, and to annexations... Enough, it’s time to stop; it’s time to look back at our calluses, at our rags, and begin to live our own inner life... It’s time for us to finally understand where the walls of our home end, and where a foreign land begins [Markov, 1884].

This passage is saturated by a general sense of depression. We get a sense of the dire implications of misunderstanding the purpose of seizing such large tracts of new territories. The horror resulting from these megalomaniac ambitions are probably impossible to stop.

Where do the walls of our house end?

Even after 140 years, this question is still relevant for this country.

Even after 140 years, this question is still relevant for this country.

Where Do the Walls of Our House End?

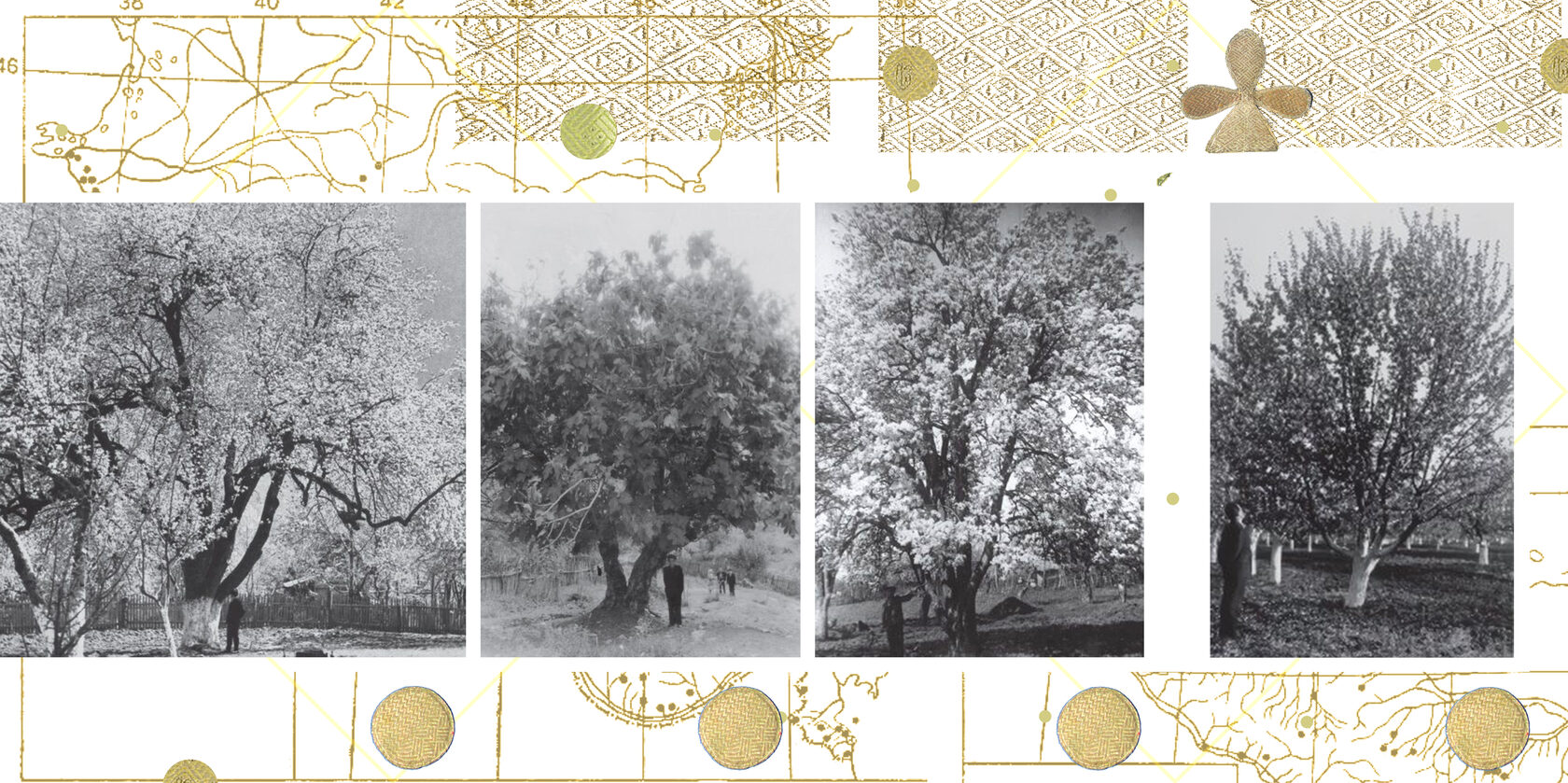

Nukh Thagushev was born in 1908, in the Circassian village of Aguy-Shapsug, on the coast of the Black Sea. As a child, he heard astounding stories from old Shapsugs about bountiful gardens that bloom every year in the mountains and boiling white and pink blossoms in the spring, all near abandoned Circassian farms and villages. At that time, many people still remembered the Caucasian Wa and some had even taken part in it.

After Thagushev graduated from technical school, he obtained a PhD from the Agricultural Institute, where he studied literature and archival materials on the history of Adyghe fruit growing. The young specialist visited many libraries, museums and archives in Krasnodar, Tbilisi, Moscow and Leningrad. In the summer, he went to mountain villages, asking about the Circassian gardens. As his research progressed, his knowledge of the history of Adyghe gardening became increasingly nuanced and developed.

Nukh Thagushev rediscovered and documented the heritage of Circassian orchards, initiating the integration of the Adyghes' indigenous knowledge into the Soviet system of academic agricultural science. He would go on to become the first Doctor of Agricultural Sciences of Adyghe origin.

Scientific study of the Circassian gardens was also legitimized by one of the most influential Soviet biologists and breeders, Ivan Michurin. The scientist vehemently admired the Adyghe fruit orchards. In 1934, he wrote:

After Thagushev graduated from technical school, he obtained a PhD from the Agricultural Institute, where he studied literature and archival materials on the history of Adyghe fruit growing. The young specialist visited many libraries, museums and archives in Krasnodar, Tbilisi, Moscow and Leningrad. In the summer, he went to mountain villages, asking about the Circassian gardens. As his research progressed, his knowledge of the history of Adyghe gardening became increasingly nuanced and developed.

Nukh Thagushev rediscovered and documented the heritage of Circassian orchards, initiating the integration of the Adyghes' indigenous knowledge into the Soviet system of academic agricultural science. He would go on to become the first Doctor of Agricultural Sciences of Adyghe origin.

Scientific study of the Circassian gardens was also legitimized by one of the most influential Soviet biologists and breeders, Ivan Michurin. The scientist vehemently admired the Adyghe fruit orchards. In 1934, he wrote:

I have known for a long time about the amazing wealth of the old Circassian gardens. Wild thickets of fruit and berry plants in Adygea represent the most valuable source material for breeders of the Caucasus. But, unfortunately, they are not used at all. In this regard, there is a serious danger for the country to forever lose, perhaps, the only specimens in the whole world of the forms of fruit plants initial for selection [Michurin, 1948].

The appearance of Maykop, the capital of Adygea, on the horticultural map of the Soviet Union was yet another watershed moment in the history of the gardens. Geneticist Nikolai Vavilov considered the territory of the North Caucasus to be the central genetic laboratory on the planet for the formation of species and varieties of many wild fruit plants. In 1930, as a result of his efforts, the Maikop Experimental Station of the All-Union Institute of Plant Growing of the USSR Academy of Sciences was established in the foothills of Adygea. Today, it houses one of the world's largest genetic collections of fruit trees. Circassian indigenous cultivars have been preserved here since 1944. Particular emphasis has always been placed on varieties of folk selection, precisely because they have adaptive characteristics to local conditions.

Unlike Michurin, who would become one of the central heroes in the USSR in the late Stalin era, in terms of the formation of a state narrative dedicated to the unique and original roots of Soviet science, Vavilov would fall under the wheels of a political campaign to persecute and discredit genetics as a science. He would eventually be repressed and die in prison.

In the time of the Stalinist Purge, Nukh Thagushev began work on studying the Adyghe gardens from 1939 to 1941 on the southern slope of the Caucasus Range within the Krasnodar Region. This work was interrupted by WWII. In 1945, research was resumed and continued until 1953, predominantly on the northern slope of the Caucasus Range and partly in the Black Sea regions.

Thagushev's work is striking in its meticulousness. He tried to reconstruct the path of Russian travelers at the turn of the nineteenth century in order to discover traces of what they saw and find confirmation of the practices they described. For example, guided by the data of I.S. Khatisov (“Babukov village... is covered with beautiful arable land and fruit trees: apple trees, pears, cherries...”), he arrived at the village in 1953 and discovered the same trees that Khatisov had seen: “What’s amazing is that although these trees are more than 80-100 years old, they are completely healthy and produce a bountiful harvest” [Tkhagushev N., 2008]. Khatisov wrote about a walnut alley in the Gastagakey tract, and Nukh found this alley too.

Tkhagushev’s work would be impossible without the bearers of Adyghe horticultural practice; the names of master grafters appear on the pages of his scientific works. For example, the village named after Kuibyshev (Aguy) in the Tuapse region is known for Natkho Shakhankeriy and Shkhalakhov Salim; in the Lazarevsky district in the II Krasno-Alexandrovsky village — Nibo Khadzhibiram; in the village of Bolshoy Kichmai — Khusht Krymcheriy; in the village of Maly Kichmay — Tlif Sharakhmet.

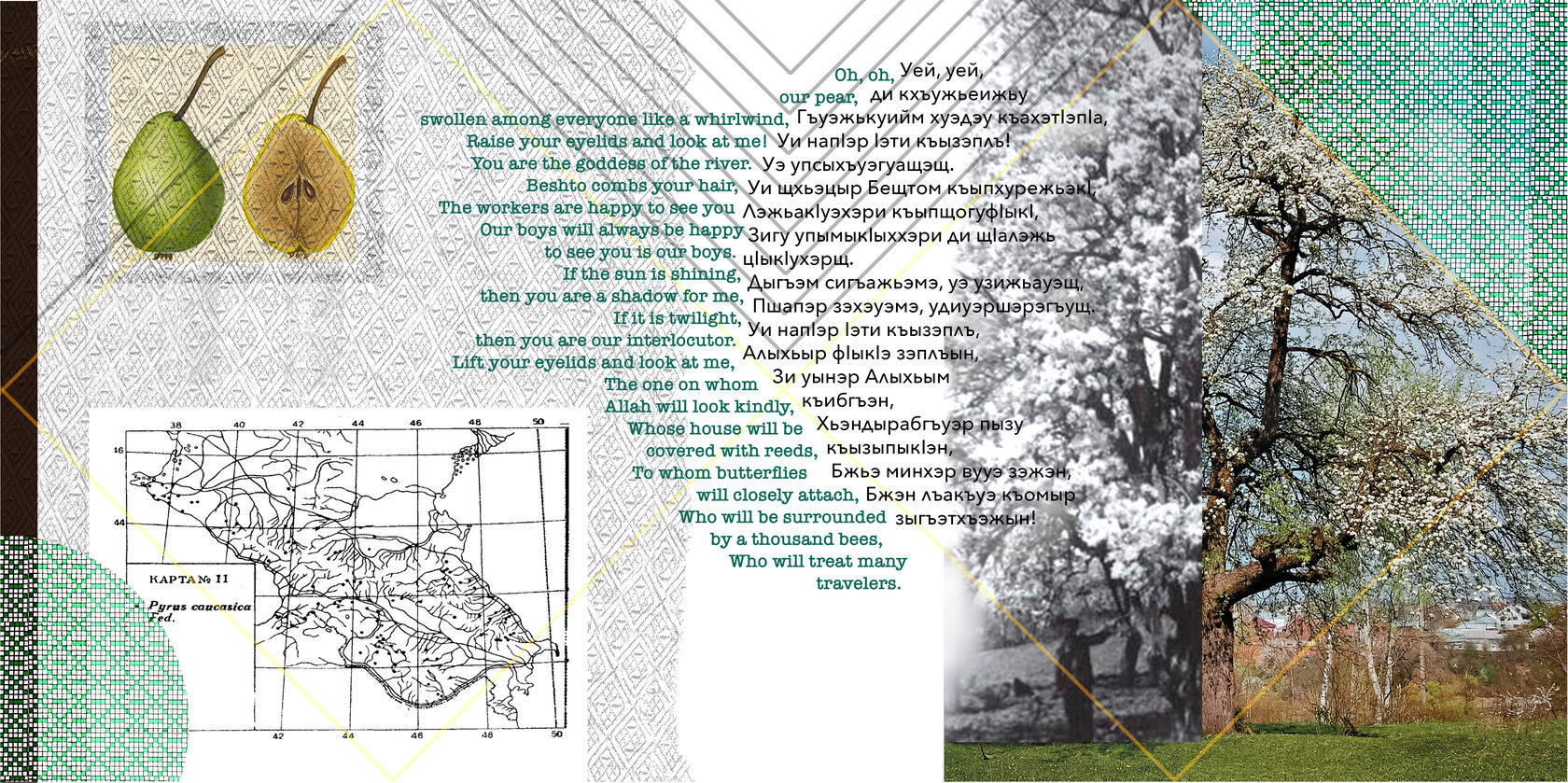

In 1946, Nukh Tkhagushev defended his thesis on “Adyghe (Circassian) Varieties of Apple and Pear Trees,” and in 1955, he defended his thesis for the degree of Doctor of Agricultural Sciences on the topic “Adyghe (Circassian) Orchards”. Tkhagushev identified 13 Circassian varieties of apple trees and 9 varieties of pear trees, 3 varieties of quince, plum and cherry each. The names of many Adyghe varieties reflect their local origin. For example, Mokoonugokuzh translated from Adyghe means “pear of the haymaking season”, Bzhelyakokuzh — “pear from Bzhelyako”, Aguemiy — “apple tree from Aguy”, Psebashkhamiy — “apple from the valley of the river Psybe”. Often local pear varieties bore the name of a person who took scions from pear trees that grew in former Adyghe orchards and made grafts. These variety names preserve the memory of folk breeders. For example, the popular name of the Aguemiy variety — Ebrukomiy (Ebruko apple) appeared as a result of the fact that after the Caucasian War in 1864, when the village of Karpovsky was settled in the valley of the Ague River, the experienced amateur gardener Napso Ebruk from the Khorokhotam tract cut scions in the former Circassian garden and grafted them into wild trees on his land. Subsequently, residents of neighboring villages took grafts from Ebruk and propagated them. The trees from which Ebruk Napso took grafts 90 years ago remained completely healthy and bore fruit abundantly.

It is worth noting that Circassian cultivars currently do not have industrial value, but exclusively cultural, historical and genetic value: resistance to parasites, endurance, adaptability to local conditions, productivity, keeping quality, transportability and resistance to low temperatures.. In this context, Soviet pomology made use of all these properties and resorted to hybrid formation — directed selection and crossing of Adyghe and European cultivars. The combination of positive traits of Adyghe and European varieties was intended to ensure the development of new varieties that successfully combine ecological adaptability to local conditions, high taste qualities and beauty (bright color) of fruits that meet basic industrial requirements and standards.

There’s a striking resemblance between the strategies of “phyto-miscegenation,” the crossing of cultivars from different origins, and the cultural engineering embedded in Soviet national policy. In many ways, the scientist himself was a product of such a synthesis—a true “in-between” figure. He navigated the tension between Soviet governance, with its policy of enforced Russification, and the native struggle for land autonomy, as well as bridging the divide between academic scholarship and indigenous knowledge.

After his death, Nukh Tkhagushev’s hazelnut plantation was dug up and destroyed, repeating the fate of the Circassian gardens.

Unlike Michurin, who would become one of the central heroes in the USSR in the late Stalin era, in terms of the formation of a state narrative dedicated to the unique and original roots of Soviet science, Vavilov would fall under the wheels of a political campaign to persecute and discredit genetics as a science. He would eventually be repressed and die in prison.

In the time of the Stalinist Purge, Nukh Thagushev began work on studying the Adyghe gardens from 1939 to 1941 on the southern slope of the Caucasus Range within the Krasnodar Region. This work was interrupted by WWII. In 1945, research was resumed and continued until 1953, predominantly on the northern slope of the Caucasus Range and partly in the Black Sea regions.

Thagushev's work is striking in its meticulousness. He tried to reconstruct the path of Russian travelers at the turn of the nineteenth century in order to discover traces of what they saw and find confirmation of the practices they described. For example, guided by the data of I.S. Khatisov (“Babukov village... is covered with beautiful arable land and fruit trees: apple trees, pears, cherries...”), he arrived at the village in 1953 and discovered the same trees that Khatisov had seen: “What’s amazing is that although these trees are more than 80-100 years old, they are completely healthy and produce a bountiful harvest” [Tkhagushev N., 2008]. Khatisov wrote about a walnut alley in the Gastagakey tract, and Nukh found this alley too.

Tkhagushev’s work would be impossible without the bearers of Adyghe horticultural practice; the names of master grafters appear on the pages of his scientific works. For example, the village named after Kuibyshev (Aguy) in the Tuapse region is known for Natkho Shakhankeriy and Shkhalakhov Salim; in the Lazarevsky district in the II Krasno-Alexandrovsky village — Nibo Khadzhibiram; in the village of Bolshoy Kichmai — Khusht Krymcheriy; in the village of Maly Kichmay — Tlif Sharakhmet.

In 1946, Nukh Tkhagushev defended his thesis on “Adyghe (Circassian) Varieties of Apple and Pear Trees,” and in 1955, he defended his thesis for the degree of Doctor of Agricultural Sciences on the topic “Adyghe (Circassian) Orchards”. Tkhagushev identified 13 Circassian varieties of apple trees and 9 varieties of pear trees, 3 varieties of quince, plum and cherry each. The names of many Adyghe varieties reflect their local origin. For example, Mokoonugokuzh translated from Adyghe means “pear of the haymaking season”, Bzhelyakokuzh — “pear from Bzhelyako”, Aguemiy — “apple tree from Aguy”, Psebashkhamiy — “apple from the valley of the river Psybe”. Often local pear varieties bore the name of a person who took scions from pear trees that grew in former Adyghe orchards and made grafts. These variety names preserve the memory of folk breeders. For example, the popular name of the Aguemiy variety — Ebrukomiy (Ebruko apple) appeared as a result of the fact that after the Caucasian War in 1864, when the village of Karpovsky was settled in the valley of the Ague River, the experienced amateur gardener Napso Ebruk from the Khorokhotam tract cut scions in the former Circassian garden and grafted them into wild trees on his land. Subsequently, residents of neighboring villages took grafts from Ebruk and propagated them. The trees from which Ebruk Napso took grafts 90 years ago remained completely healthy and bore fruit abundantly.

It is worth noting that Circassian cultivars currently do not have industrial value, but exclusively cultural, historical and genetic value: resistance to parasites, endurance, adaptability to local conditions, productivity, keeping quality, transportability and resistance to low temperatures.. In this context, Soviet pomology made use of all these properties and resorted to hybrid formation — directed selection and crossing of Adyghe and European cultivars. The combination of positive traits of Adyghe and European varieties was intended to ensure the development of new varieties that successfully combine ecological adaptability to local conditions, high taste qualities and beauty (bright color) of fruits that meet basic industrial requirements and standards.

There’s a striking resemblance between the strategies of “phyto-miscegenation,” the crossing of cultivars from different origins, and the cultural engineering embedded in Soviet national policy. In many ways, the scientist himself was a product of such a synthesis—a true “in-between” figure. He navigated the tension between Soviet governance, with its policy of enforced Russification, and the native struggle for land autonomy, as well as bridging the divide between academic scholarship and indigenous knowledge.

After his death, Nukh Tkhagushev’s hazelnut plantation was dug up and destroyed, repeating the fate of the Circassian gardens.

Nukh Thagushev: Academicization of Indigenous Knowledge

A number of Adyghe trees, both sacred and cultural,were destroyed during Soviet times. For example, near the village of Gatlukai grew the “tree of Islam” (Islam ichyig) — a huge five-hundred-year-old oak tree, more than thirty meters high. This famous tree, bearing the name of the brave Islam, who gave his life for the freedom of his land, was cut down during the construction of the Kuban reservoir in the 1970s.

During World War II, all sanatoriums and holiday homes in Sochi were repurposed as evacuation hospitals. Due to the lack of iodine, it was customary to make it from young nuts, which caused irreparable harm to the trees. A participant in these events recalls:

During World War II, all sanatoriums and holiday homes in Sochi were repurposed as evacuation hospitals. Due to the lack of iodine, it was customary to make it from young nuts, which caused irreparable harm to the trees. A participant in these events recalls:

In the spring, residents of the coast were sent to the forest to knock down nuts that were still milky. I also collected a nut, which was crushed and iodine was prepared from it. It was real iodine, it was used in evacuation hospitals. In order to knock down a still green nut, you had to hit the branches with great force; the impact broke small branches and knocked out the bark. Almost all the trees became diseased, and it took years for them to recover. But even in the post-war period, the nut suffered in full. Walnut trees, which gave an excellent harvest, were destroyed on the vine, and they began to make stocks for guns and assault rifles from them [Kuek, Kuek, 2015].

In a staggeringly ironic turn of events, the Circassian gardens continued their life cycle in the form of medicine and weapons for murder.

Losses in Soviet Times: Iodine and Gun Stocks from Circassian Trees

The loss of trees in the Circassian gardens continues in our time. For example, in 2021, four pear and two apple trees both over 300 years old, were cut down in the Adyghe village of Khamyshki. They were felled by the owner of the land, who wanted to build a new house. The destruction of trees often occurs by accident; people do not have adequate information or education about the importance of the Circassian fruit trees and therefore cut them down when building houses and dachas, in particular in the mountainous part of the Republic, especially if the trees interfere with economic activity.

Activists like Igor Ogai, a member of the Adyghe branch of the Russian Geographical Society and the Public Chamber of the Republic of Adygea, have been working to include these trees in the list of natural and cultural heritage sites. Their goal is to secure protected status for the trees and develop a strategic plan to have them recognized on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

These plans are being hampered by bureaucracy. Igor says that the Department for the Protection and Use of Cultural Heritage Objects of Adygea told him that since these are trees, they are natural monuments, and therefore under the jurisdiction of the Department for Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of the Republic of Adygea. This department stated that since the trees are grafted, they are cultural, rather than natural heritage. While the status of the trees remains undecided, a resident of the village of Khamyshki, Ilyas Farkhatov, is using his own resources to create a “Museum of Pears of Ancient Circassia”.

In 2021, a round table titled “The Circassian Garden in the Space of Sociocultural Transformation” was held, which became a platform for consolidating representatives of professional communities in the research and preservation of the Circassian gardens. As Maxim Shapovalov, editor of the Red Book of Adygea, noted at the round table, we are now approaching a critical point when, over the next few decades, many valuable trees will die from old age, so the question is not only in their study and inventory, but also in the preservation of trees;for example, in the selection of grafts and their fixation on the basis of collections, in particular, the Maikop Experimental Station of the All-Russian Institute of Genetic Resources.

Since the life of fruit trees is not overly long (although for long-lived pears it is approximately 200 years) and because after about 50 years Circassian fruit trees may completely disappear, specialists in the field of agriculture, horticulture, agricultural technologies, pomology, plant genetics, activists, experts in history and heritage face a range of challenging tasks. This includes the inventory and certification of trees in the region, the compilation of accurate maps indicating the geolocation of each tree studied, and the creation of tree passports. Such a description may contribute to the granting of special protection status to trees.

Also, it is necessary to take grafts from the most remarkable specimens of Circassian varieties that stand out for certain characteristics, for example, resistance to fungal phytopathogens for further consolidation of the cultivars in the collection of genetic resources. In the future, it is necessary to take samples to study the DNA of these varieties on the basis of plant genetic research laboratories and create a genomic collection of cultivars of folk selection. The presence of such a collection will significantly simplify genomic research and mark the beginning of genetic certification of varieties, which is of strategic importance for their identification and subsequent use in breeding work.

According to approximate calculations of experts, a small amount of one million rubles is required for tree certification. Unfortunately, at the moment, the implementation of these tasks, which lie exclusively in the field of horticultural knowledge, selection and genetics, is extremely complicated due to the politicization of the issue of the Circassian gardens and the existing self-censorship on conducting such research among those representatives in the professional community who make decisions and can influence resource distribution. Since the topic of the Circassian gardens is directly related to the contested heritage of the Russo-Circassian War, working with this context can potentially threaten professional careers.

However, attempts at public conversation continue. Nuret Kudaeva, the great-niece of Nukh Thagushev, makes a significant contribution to the consolidation of experts working on this topic, holding round tables and building on interdisciplinary discussions. In June 2023, she became one of the initiators of the round table “Revival of Old Adyghe Varieties of Fruit Crops”, which was attended by representatives of various professional communities, as well as representatives of government agencies, non-profit organizations, and grassroots initiatives. As a result of the round table, a resolution was adopted on further joint activities of scientific and cultural organizations in the region to revive Old Adyghe varieties of fruit crops.

Activists like Igor Ogai, a member of the Adyghe branch of the Russian Geographical Society and the Public Chamber of the Republic of Adygea, have been working to include these trees in the list of natural and cultural heritage sites. Their goal is to secure protected status for the trees and develop a strategic plan to have them recognized on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

These plans are being hampered by bureaucracy. Igor says that the Department for the Protection and Use of Cultural Heritage Objects of Adygea told him that since these are trees, they are natural monuments, and therefore under the jurisdiction of the Department for Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of the Republic of Adygea. This department stated that since the trees are grafted, they are cultural, rather than natural heritage. While the status of the trees remains undecided, a resident of the village of Khamyshki, Ilyas Farkhatov, is using his own resources to create a “Museum of Pears of Ancient Circassia”.

In 2021, a round table titled “The Circassian Garden in the Space of Sociocultural Transformation” was held, which became a platform for consolidating representatives of professional communities in the research and preservation of the Circassian gardens. As Maxim Shapovalov, editor of the Red Book of Adygea, noted at the round table, we are now approaching a critical point when, over the next few decades, many valuable trees will die from old age, so the question is not only in their study and inventory, but also in the preservation of trees;for example, in the selection of grafts and their fixation on the basis of collections, in particular, the Maikop Experimental Station of the All-Russian Institute of Genetic Resources.

Since the life of fruit trees is not overly long (although for long-lived pears it is approximately 200 years) and because after about 50 years Circassian fruit trees may completely disappear, specialists in the field of agriculture, horticulture, agricultural technologies, pomology, plant genetics, activists, experts in history and heritage face a range of challenging tasks. This includes the inventory and certification of trees in the region, the compilation of accurate maps indicating the geolocation of each tree studied, and the creation of tree passports. Such a description may contribute to the granting of special protection status to trees.

Also, it is necessary to take grafts from the most remarkable specimens of Circassian varieties that stand out for certain characteristics, for example, resistance to fungal phytopathogens for further consolidation of the cultivars in the collection of genetic resources. In the future, it is necessary to take samples to study the DNA of these varieties on the basis of plant genetic research laboratories and create a genomic collection of cultivars of folk selection. The presence of such a collection will significantly simplify genomic research and mark the beginning of genetic certification of varieties, which is of strategic importance for their identification and subsequent use in breeding work.

According to approximate calculations of experts, a small amount of one million rubles is required for tree certification. Unfortunately, at the moment, the implementation of these tasks, which lie exclusively in the field of horticultural knowledge, selection and genetics, is extremely complicated due to the politicization of the issue of the Circassian gardens and the existing self-censorship on conducting such research among those representatives in the professional community who make decisions and can influence resource distribution. Since the topic of the Circassian gardens is directly related to the contested heritage of the Russo-Circassian War, working with this context can potentially threaten professional careers.

However, attempts at public conversation continue. Nuret Kudaeva, the great-niece of Nukh Thagushev, makes a significant contribution to the consolidation of experts working on this topic, holding round tables and building on interdisciplinary discussions. In June 2023, she became one of the initiators of the round table “Revival of Old Adyghe Varieties of Fruit Crops”, which was attended by representatives of various professional communities, as well as representatives of government agencies, non-profit organizations, and grassroots initiatives. As a result of the round table, a resolution was adopted on further joint activities of scientific and cultural organizations in the region to revive Old Adyghe varieties of fruit crops.

Future for The Circassian Gardens?

In 1914, an anonymous author wrote that during the eviction, the Circassians, unable to take their belongings with them, buried the most valuable items in the ground and hid them in secluded places: in cauldrons, copper utensils, scythes, sickles. The mountain springs were covered with felt and turf. They burned houses and buildings when Russian troops failed to do so. They set fire to bread and hay. However, they did not touch arable lands, meadows and gardens. “Apparently”, the author reflects, “many had a glimmer of hope that perhaps the time would come when they would return to their homeland and occupy their ashes. This partly explains why... the hand of the highlanders did not touch the gardens” [Kuban, 1914].

The author continues:

The author continues:

From the point of view of history and economics, it was a quick and traceless destruction of the most ancient culture... After this culture, nothing remained in place — neither capital in the form of dwellings, buildings and outbuildings, nor working equipment — agricultural tools, except for rusty scythes and sickles, no animals, no household items, nothing, in a word, material... Only Circassian gardens remained... [Kuban, 1914]

Over the past five to six generations, Circassians outside the North Caucasus have lived in hope of returning to their homeland. The process of Circassian repatriation became possible only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and has intensified in the last few decades. Where the Motherland used to be, is now a completely unfamiliar and foreign country. The old Circassian gardens have only a few decades left to live. Soon, if no measures are taken, they will perish. In the meantime, the Circassian gardens remain standing, awaiting the return of the people who tended to and cultivated them.

"Only Circassian Gardens Remain...": Gardens and Hope for Return

[Clarke, 1811] Clarke Ed. Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. Part one. Russia, Tartary, and Turkey. Philadelphia: Anthony Finley, 1811.

[Drozdov, 1877] Drozdov I. The last struggle with the highlanders in the Western Caucasus // Caucasian collection. 1877. Vol. 2 [Дроздов И. Последняя борьба с горцами на Западном Кавказе // Кавказский сборник. 1877. Т. 2].

[Fadeev, 1889] Fadeev R.A. Letters from the Caucasus // Collected Works. Vol. 1. Part 1. St. Petersburg, 1889 [Фадеев Р.А. Письма с Кавказа // Собрание сочинений. Т. 1. Ч. 1. СПб., 1889].

[Grebnitsky, 1908] Grebnitsky A. Two Circassian apples // Fruit growing. - 1908. - No. 9 [Гребницкий А. Два черкесских яблока // Плодоводство. - 1908. - № 9].

[Khatisov, 1867] Khatisov I. S. Report of the commission to study lands on the north-eastern shore of the Black Sea, between the Tuapse and Bzyb rivers // Notes of the Caucasian Society of Agriculture. Tiflis, 1867. No. 5–6 [Хатисов И. С. Отчет комиссии по исследованию земель на северо-восточном берегу Черного моря, между реками Туапсе и Бзыбью // Записки Кавказского общества сельского хозяйства. Тифлис, 1867. № 5–6].

[Khristianovich, 1917] Khristianovich V. From a trip along the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus // Black Sea Agriculture. Sukhum. - 1917. - No. 3-4 [Христианович В. Из поездки по черноморскому побережью Кавказа // Черноморское сельское хозяйство. - Сухум. - 1917. - № 3-4]

[Klingen, 1897] Klingen I.N. Basics of farming in the Sochi district. St. Petersburg, 1897 [Клинген И.Н. Основы хозяйства в Сочинском округе. СПб., 1897].

[Krasnov, 1895] Krasnov A.N. Russian tropics // Historical Bulletin. - 1895. - Issue 2 [Краснов А.Н. Русские тропики // Исторический вестник. - 1895. - Вып. 2].

[Krivenko, 1893] Krivenko V.S. Essays on the Caucasus. A trip to the Caucasus in the fall of 1888. St. Petersburg, 1893 [Кривенко В.С. Очерки Кавказа. Поездка на Кавказ осенью 1888 года. СПб, 1893].

[Kuban, 1914] Kuban and the Black Sea coast. Reference book. Ekaterinodar, 1914 [Кубань и Черноморское побережье. Справочная книга. Екатеринодар, 1914].

[Kuek, Kuek, 2015] Kuek A.S., Kuek M.G. Sacred tree among the Circassians // Sanctuaries of the Abkhazians and holy places of the Circassians: a comparative typological study. Maykop, 2015 [Куек А.С., Куек М.Г. Священное дерево у адыгов // Святилища абхазов и святые места адыгов: сравнительно-типологическое исследование. Майкоп, 2015].

[Kuznetsov, 1890] Kuznetsov N. The state of gardening in the Black Sea region // Agriculture and forestry. St. Petersburg, 1890. - Part CLXIII [Кузнецов Н. Состояние садоводства в Черноморском округе // Сельское хозяйство и лесопроизводство. СПб, 1890. - Ч. CLXIII].