Fallout zones

This project examines the communities, ecologies, and economies around the Baikonur and Plesetsk Cosmodromes, focusing on how the Russian space industry shapes these environments. By exploring the politics and ecology of these sites, the project investigates how space exploration advances while simultaneously perpetuating systematic inequality, environmental injustice, and providing livelihoods.

>

>

1/3

This project advances a materially informed perspective on the work of the Russian space industry. At the start of the project, discarded rocket wreckage became the key object that helped me to locate communities, ecologies, and economies that form around the space infrastructures. Building on the long-term ethnographic fieldwork I was able to further expand my research towards the key centres of the space industry, getting a chance to work in the city of Baikonur and attend space launches there. As I was spending weeks and months with people involved in the work of the space industry, photography helped me to uncover complex social phenomena I have encountered during my work. I turned to photography not just as a tool for documentation and analysis but as a means to create visual narratives that communicate the complexities of the relationship between people and their immediate environments. My own practice, combined with a museological approach to the documentation of social realities, seeks to unravel layered histories through a nuanced, material engagement with the artefacts of space exploration. I employ photography to explore the tension between the visible and the invisible in the landscapes affected by Soviet modernising projects and space exploration. Essentially, this project builds links between disparate sites and fleeting moments that reflect the deeper socio-political and environmental conditions in and around Baikonur or Plesetsk Cosmodromes. In this context, photography becomes an act of excavation, bringing to the surface the narratives of those living in proximity to these zones of technological ambition and environmental decline.

Recovery operation of a Soyuz rocket booster discarded in Central Kazakhstan

Series of photographs of an impact site from 2007 Proton rocket crash

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

The intersecting themes of environmental degradation, economic survival, cultural resilience, and agency amidst adversity are further elaborated by the archival materials. Working with private photo and video archives helps to elucidate implicit meanings and situated narratives found on the fringes of space industry. By juxtaposing contemporary images with archival footage, I aim to create a dialogue between different temporalities and perspectives, revealing how memory, history, and myth converge in these contested spaces. This approach not only foregrounds the lived experiences of the people but also critiques the broader geopolitical imaginaries that shape and are shaped by the space industry.

A man poses in front of a rocket fuel tank fragment during an environmental assessment conducted by local activists. Courtesy of Albert Loginov, 2005

text

2/3

Baikonur: Politics and Ecology of Space Exploration

For Russia, outer space presents an important geopolitical arena. It is a space onto which the state’s social, economic, technological, and military potency has been projected since the inception of the Soviet space program. Today, Cosmodrome Baikonur, Russia’s main gateway to space, with its grand infrastructure, is an important stage for the performance of the state's sovereignty in the face of competing nation-states and private enterprises. However, Russia’s access to space from Baikonur hinges on a delicate political arrangement with Kazakhstan, where the Cosmodrome is located. Since the early 1990s, the Cosmodrome, along with the adjacent city of Baiqonyr and fallout zones (lands designated for jettisoning of rocket boosters), have been leased by Russia from Kazakhstan for $115 million per year. In 2020, the lease was prolonged for another 30 years. For the duration of the lease, nearly 70,000 people, of which about 21,000 are Russian citizens, along with Baikonur’s enterprises and administrative organisations are governed by Russian law with the city’s legal status equal to that of Russia's federal city.

Today, Baikonur still remains at the heart of the Russian space economy but its future is uncertain. In the 2000s military units stationed there were transferred to the northern Cosmodrome Plesetsk, while the development of the Vostochny Cosmodrome, a new launch site in the Amur region, took away resources from Baikonur. Baikonur’s importance is gradually winding down as it is largely charged with the maintenance of the International Space Station and the delivery of heavy-payloads to geostationary orbits. Whereas in Kazakhstan, visions of the techno-scientific progress associated with space exploration are part of state developmentalist narratives that stress the promises of Baikonur. From the early days of independence, the Soviet space legacy inherited by Kazakhstan was celebrated by Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first president of Kazakhstan, as a valuable asset for the national technological advancement and assertion of state sovereignty. However, Baikonur and its lease agreement unsettles Russian and Kazakhstani state discourses. Within the city, where the power is wielded by Russia, Kazakhstani citizens are left to negotiate conflicting Russian-Kazakhstani sovereign projects and modes of governance within Baikonur. Russian citizens are gradually preparing to leave the city for good, while people living in the vicinity of the Cosmodrome question Russia’s continuous presence in the region.

For Russia, outer space presents an important geopolitical arena. It is a space onto which the state’s social, economic, technological, and military potency has been projected since the inception of the Soviet space program. Today, Cosmodrome Baikonur, Russia’s main gateway to space, with its grand infrastructure, is an important stage for the performance of the state's sovereignty in the face of competing nation-states and private enterprises. However, Russia’s access to space from Baikonur hinges on a delicate political arrangement with Kazakhstan, where the Cosmodrome is located. Since the early 1990s, the Cosmodrome, along with the adjacent city of Baiqonyr and fallout zones (lands designated for jettisoning of rocket boosters), have been leased by Russia from Kazakhstan for $115 million per year. In 2020, the lease was prolonged for another 30 years. For the duration of the lease, nearly 70,000 people, of which about 21,000 are Russian citizens, along with Baikonur’s enterprises and administrative organisations are governed by Russian law with the city’s legal status equal to that of Russia's federal city.

Today, Baikonur still remains at the heart of the Russian space economy but its future is uncertain. In the 2000s military units stationed there were transferred to the northern Cosmodrome Plesetsk, while the development of the Vostochny Cosmodrome, a new launch site in the Amur region, took away resources from Baikonur. Baikonur’s importance is gradually winding down as it is largely charged with the maintenance of the International Space Station and the delivery of heavy-payloads to geostationary orbits. Whereas in Kazakhstan, visions of the techno-scientific progress associated with space exploration are part of state developmentalist narratives that stress the promises of Baikonur. From the early days of independence, the Soviet space legacy inherited by Kazakhstan was celebrated by Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first president of Kazakhstan, as a valuable asset for the national technological advancement and assertion of state sovereignty. However, Baikonur and its lease agreement unsettles Russian and Kazakhstani state discourses. Within the city, where the power is wielded by Russia, Kazakhstani citizens are left to negotiate conflicting Russian-Kazakhstani sovereign projects and modes of governance within Baikonur. Russian citizens are gradually preparing to leave the city for good, while people living in the vicinity of the Cosmodrome question Russia’s continuous presence in the region.

Historically, Kazakhstan has been subjected to Soviet modernising agricultural, industrial, and military projects. These included forced collectivization, rapid industrialisation, nuclear weapons testing, intensive irrigation and monocrop agriculture. Such projects were rooted in Russian and Soviet imperial ideas, which often viewed the vast steppes and boreal forests as empty, unproductive lands. This perception justified the technological expansion and violent modernization efforts that physically and discursively reinforced the idea of "emptiness." In Baikonur state and military leaders saw the development of the Soviet space program as part of a broader effort to transform the Soviet society and environment through large-scale industrial transformation and military-technological intervention.

Once the first rockets took off Baikonur swaths of national inlands in Central Kazakhstan and Siberia were effectively turned into scrap yards littered with space debris from the 1950s onwards. Over decades rural communities of Central Kazakhstan witnessed a series of space rocket accidents that resulted in the spills of highly toxic and cancerogenic heptyl fuel. Although nowadays recovery brigades clean up the steppes shortly after launches, continuous launches from Baikonur still provoke dissent among the people, whose homes and grazing pastures are located nearby fallout zones. For the communities living in the vicinity of the zones, they present a profoundly ambiguous landscape, which simultaneously threatens their health and well-being through invisible pollution, and offers the means to sustain their households by salvaging space debris or seeking compensation from the state for health concerns.

Once the first rockets took off Baikonur swaths of national inlands in Central Kazakhstan and Siberia were effectively turned into scrap yards littered with space debris from the 1950s onwards. Over decades rural communities of Central Kazakhstan witnessed a series of space rocket accidents that resulted in the spills of highly toxic and cancerogenic heptyl fuel. Although nowadays recovery brigades clean up the steppes shortly after launches, continuous launches from Baikonur still provoke dissent among the people, whose homes and grazing pastures are located nearby fallout zones. For the communities living in the vicinity of the zones, they present a profoundly ambiguous landscape, which simultaneously threatens their health and well-being through invisible pollution, and offers the means to sustain their households by salvaging space debris or seeking compensation from the state for health concerns.

A group of hunters posing with a bear. Hunters were among the first people to explore fallout zones. Courtesy of Pavel Nasonov, 2001

Yurii and his mate approach a Soyuz rocket booster. Salvaging brigades had to spend weeks paving ways through dense forests to get the debris to the nearest village. Courtesy of Yurii Karaban', 2007

Yurii poses in front of a booster. In the Soviet times he worked as a pilot frequently flying over the fallout zones on his way to remote villages. Over the years he memorised the area from above and later became known as the best pathfinder. Courtesy of Yurii Karaban', 2007

The view of Baikonur_s central square where the headquarter of the Russian space agency stands

Mukhit aga walks over an abandoned mine

Plesetsk: Informal economies of space debris

Although the boosters discarded after launches from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, Russia’s northernmost spaceport, are tracked and mapped by the military, many still end up abandoned in the fallout zones with authorities unwilling to clear and tidy up the lands. In the Mezen river basin, much of these territories designated for jettisoning of the boosters overlapped with hunting grounds of the local rural communities. Among village men who would frequent forests, marshes, and tundra setting out on weeks-long hunting trips, rocket debris was a common site. Coming back into their villages, hunters would tell stories of glimmering objects they saw in the forest, of long greyish bodies of rockets partially submerged in the rivers, with fuel draining into the stream.

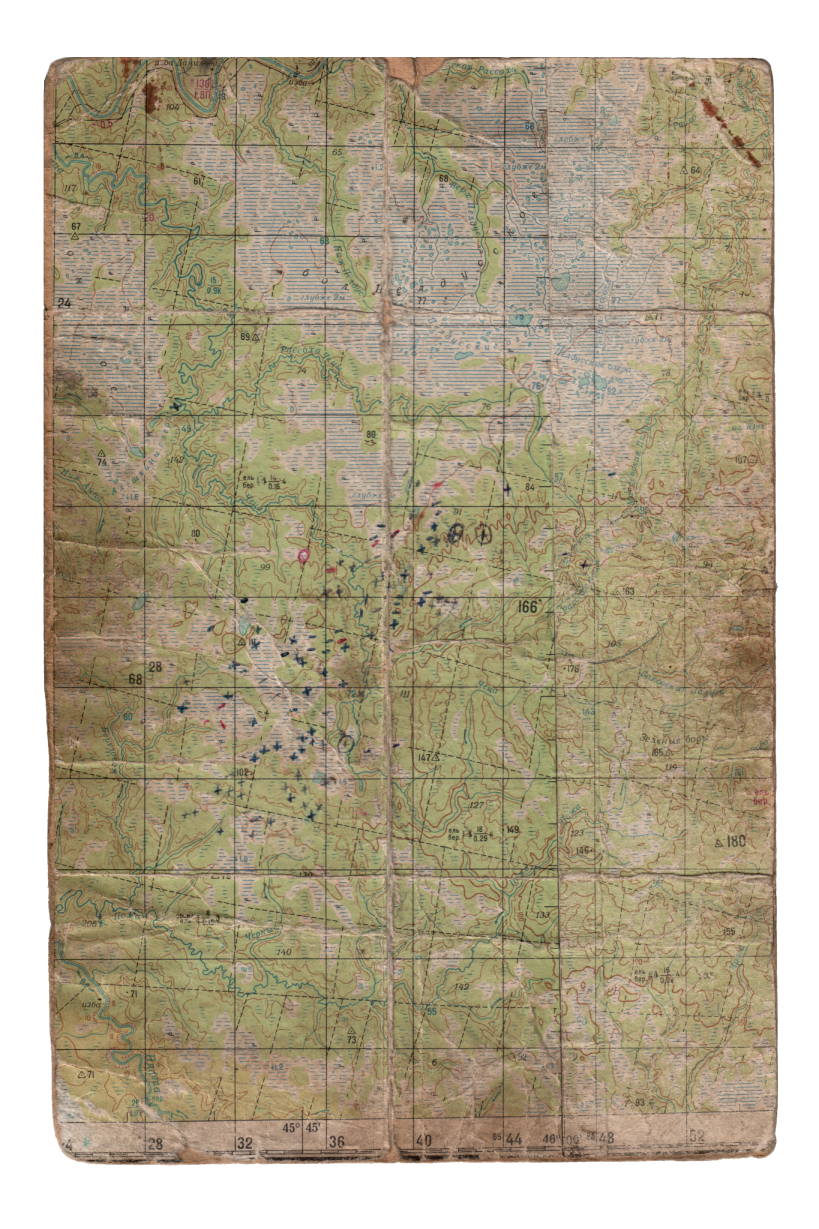

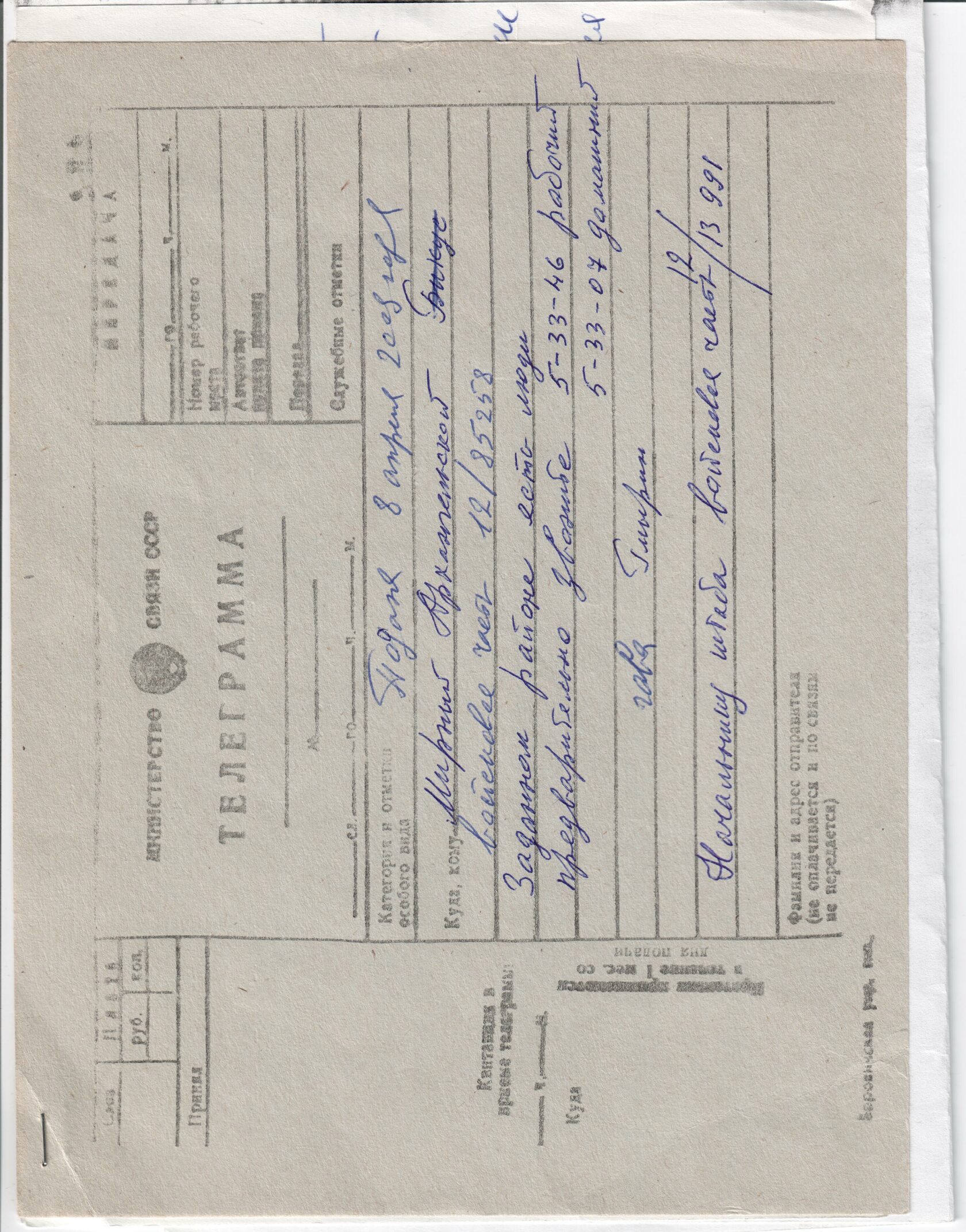

Space debris was known as a source of valuable and durable materials that could be used for manufacturing of boats, furnaces, and other household items. But it is in the context of the post-Soviet crisis and uncertainty that hunters began to frequent the fallout zones, looking for precious metals to be salvaged from the wreckage. Together with close friends and neighbours, they would spend weeks in the taiga stalking the boosters, as they combed the forests and swamps near their hunting grounds. During the summer season, they covered hundreds of kilometres, mapping and marking the wreckage they found, learning the trajectories, and trying to predict where they might find debris after the next launch. With the first snow, the hunters were returned again to saw the boosters and prepare them for transpiration. Later, by the end of winter, with a solid snow cover in place, the brigades rolled roads and built bridges over ravines and slopes of frozen rivers to transport the space metal away and sell it in regional centres.

Archival images and maps presented here come from the family albums of members of salvaging brigades who worked in the Arkhangelsk region and the Republic of Komi in the 2000s. These photographs, featuring men posing with boosters, resemble trophy portraits, capturing the pride and sense of achievement many found in their unconventional work. Each photograph is a testament to their ability to find value and purpose in the most unlikely of places, transforming space debris into a source of livelihood.

Although the boosters discarded after launches from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, Russia’s northernmost spaceport, are tracked and mapped by the military, many still end up abandoned in the fallout zones with authorities unwilling to clear and tidy up the lands. In the Mezen river basin, much of these territories designated for jettisoning of the boosters overlapped with hunting grounds of the local rural communities. Among village men who would frequent forests, marshes, and tundra setting out on weeks-long hunting trips, rocket debris was a common site. Coming back into their villages, hunters would tell stories of glimmering objects they saw in the forest, of long greyish bodies of rockets partially submerged in the rivers, with fuel draining into the stream.

Space debris was known as a source of valuable and durable materials that could be used for manufacturing of boats, furnaces, and other household items. But it is in the context of the post-Soviet crisis and uncertainty that hunters began to frequent the fallout zones, looking for precious metals to be salvaged from the wreckage. Together with close friends and neighbours, they would spend weeks in the taiga stalking the boosters, as they combed the forests and swamps near their hunting grounds. During the summer season, they covered hundreds of kilometres, mapping and marking the wreckage they found, learning the trajectories, and trying to predict where they might find debris after the next launch. With the first snow, the hunters were returned again to saw the boosters and prepare them for transpiration. Later, by the end of winter, with a solid snow cover in place, the brigades rolled roads and built bridges over ravines and slopes of frozen rivers to transport the space metal away and sell it in regional centres.

Archival images and maps presented here come from the family albums of members of salvaging brigades who worked in the Arkhangelsk region and the Republic of Komi in the 2000s. These photographs, featuring men posing with boosters, resemble trophy portraits, capturing the pride and sense of achievement many found in their unconventional work. Each photograph is a testament to their ability to find value and purpose in the most unlikely of places, transforming space debris into a source of livelihood.

Abandoned facilities of the former military garrison of Baikonur

Karsakpai, an industrial settlement located in the vicinity of Baikonur_s fallout zones

A model of Soyuz space rocket installed on the side of Baikonur's central avenue

READING LIST

SPACE IN THE TROPICS: FROM CONVICTS TO ROCKETS IN FRENCH GUIANA

Peter Redfield

CONSTELLATIONS OF INEQUALITY: SPACE, RACE, AND UTOPIA IN BRAZIL

T. Mitchell

RARE EARTH FRONTIERS: FROM TERRESTRIAL SUBSOILS TO LUNAR LANDSCAPES

Julie Michelle

OUTER SPACE TECHNOPOLITICS AND POSTCOLONIAL MODERNITY IN KAZAKHSTAN

Nelly Bekus

A CHRONOTOPE OF EXPANSION: RESISTING SPATIO-TEMPORAL LIMITS IN A KAZAKH NUCLEAR TOWN

Catherine Alexander

THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF TRAUMATIC MEMORY: KAZAKHSTAN AFTER SOVIET MODERNIZATION PROJECTS

Ulbolsyn Sandybayeva, Zhomart Medeuov, and Kulshat Medeuova

SPACE IN THE TROPICS: FROM CONVICTS TO ROCKETS IN FRENCH GUIANA

Peter Redfield

CONSTELLATIONS OF INEQUALITY: SPACE, RACE, AND UTOPIA IN BRAZIL

T. Mitchell

RARE EARTH FRONTIERS: FROM TERRESTRIAL SUBSOILS TO LUNAR LANDSCAPES

Julie Michelle

OUTER SPACE TECHNOPOLITICS AND POSTCOLONIAL MODERNITY IN KAZAKHSTAN

Nelly Bekus

A CHRONOTOPE OF EXPANSION: RESISTING SPATIO-TEMPORAL LIMITS IN A KAZAKH NUCLEAR TOWN

Catherine Alexander

THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF TRAUMATIC MEMORY: KAZAKHSTAN AFTER SOVIET MODERNIZATION PROJECTS

Ulbolsyn Sandybayeva, Zhomart Medeuov, and Kulshat Medeuova

3/3

Installation. Two landscape photographs 60x80,

seven 10X15 archival photographs, reproduction

of maps, a fragment of a Soyuz rocket booster

on a pedestal. 2023

seven 10X15 archival photographs, reproduction

of maps, a fragment of a Soyuz rocket booster

on a pedestal. 2023

installation images