SPROUTING

TO PARADISE

TO PARADISE

>

>

>

The Crimean Tatars regarded building fountains as a virtuous act, often inscribing Quranic quotes and the builder's name on them. The architectural design of each fountain was unique, reflecting the value and individuality of the water source, ensuring no two structures were alike.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

1/4

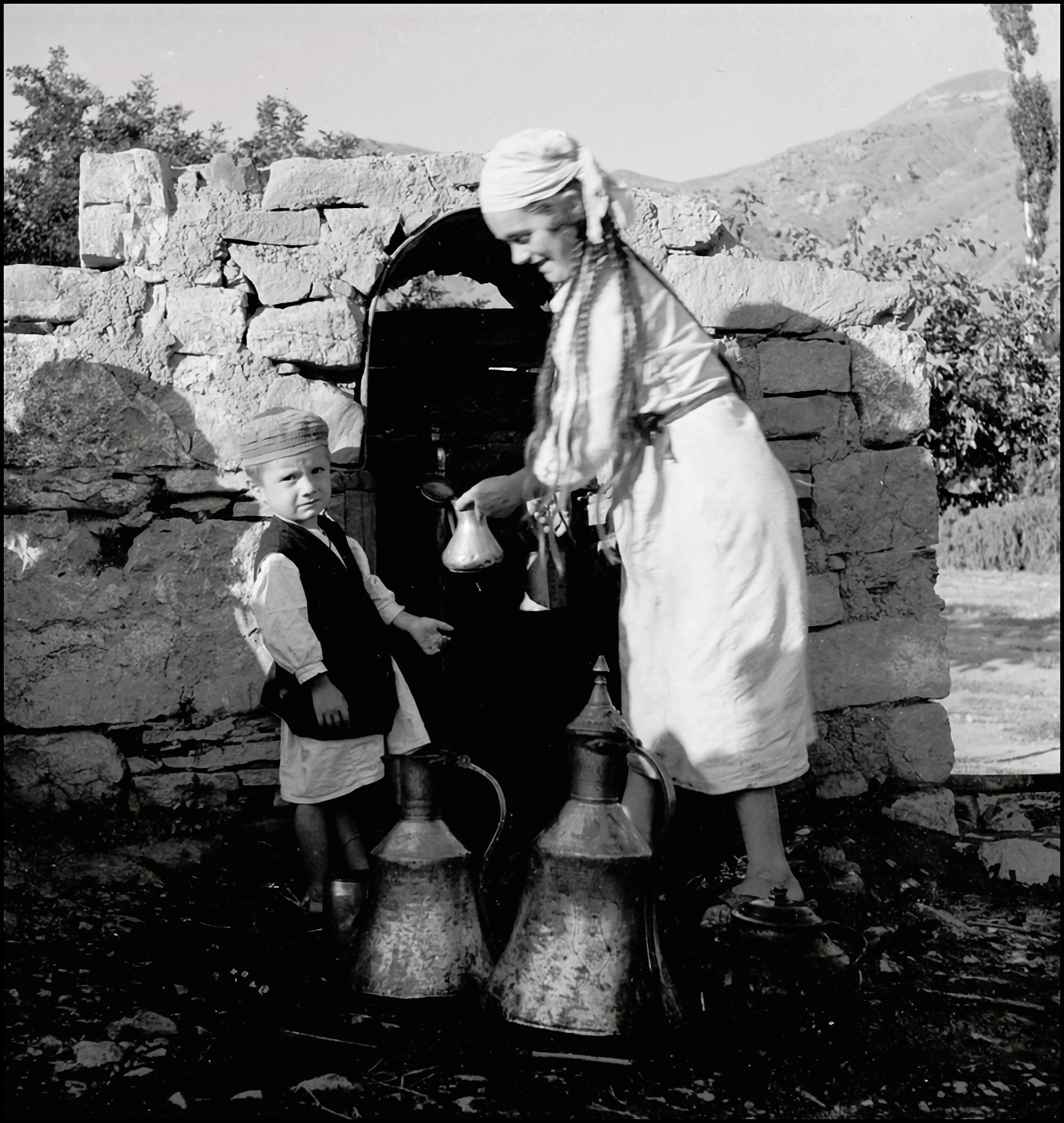

When asked why she uses so little water for household needs my Crimean Tatar great-grandmother, Hache, would respond: "Why waste more when I can make do with less?" Crimean Tatars, the indigenous Muslim people of Crimea, shaped by the ethno-genesis of various populations that resided here at different times, held a deep reverence for water, emphasizing its conservation even in times of plenty. They valued water greatly and established an extensive irrigation network across the peninsula. In the arid Crimea, every drop of water was cherished, and streams were integrated into communal water supply and irrigation systems: networks of ceramic pipes were transporting the spring water over several kilometers, culminating in the distinct architectural beauty of Crimean Tatar fountains, known as "cheshme."

The Crimean Tatars regarded building fountains as a virtuous act, often inscribing Quranic quotes and the builder's name on them. The architectural design of each fountain was unique, reflecting the value and individuality of the water source, ensuring no two structures were alike.

In May 1944, the entire Crimean Tatar population, including Hache and her children, were forcibly deported from Crimea. It is said to be the fastest operation of mass eviction in world history. After that the neglected fountains and irrigation systems began to deteriorate and became filled with garbage, destroyed, and overgrown with plants. The new mainland settlers, to whom the Soviet authorities handed over the homes of the indigenous population, lacked the knowledge of water management. In the 1950s, when the water problem and drought became particularly acute, the construction of the unified North Crimean Canal began, bringing water from the Dnipro River.

The Crimean Tatars regarded building fountains as a virtuous act, often inscribing Quranic quotes and the builder's name on them. The architectural design of each fountain was unique, reflecting the value and individuality of the water source, ensuring no two structures were alike.

In May 1944, the entire Crimean Tatar population, including Hache and her children, were forcibly deported from Crimea. It is said to be the fastest operation of mass eviction in world history. After that the neglected fountains and irrigation systems began to deteriorate and became filled with garbage, destroyed, and overgrown with plants. The new mainland settlers, to whom the Soviet authorities handed over the homes of the indigenous population, lacked the knowledge of water management. In the 1950s, when the water problem and drought became particularly acute, the construction of the unified North Crimean Canal began, bringing water from the Dnipro River.

In 2014, following Crimea's incorporation into Russia, Ukraine responded by cutting off the water supply from the Dnieper through the canal. The peninsula once again faced water shortages. In 2022, during the so-called "special military operation" by Russia in Ukraine, Russian raiding squads and airborne troops unblocked the North Crimean Canal, restoring the water supply to the peninsula. In June 2023, the Kahovka Hydroelectric Power Station was destroyed—water from the Kahovka reservoir on the Dnipro River nourished the canal. Neither Russia nor Ukraine toom responsibility for the destruction of the dam. Hydrologists predict that if the water from the reservoir stops flowing into the North Crimean Canal, it will dry up. Currently, the majority of fountains in Crimea are inactive, in ruins, or not recognized as architectural or historical monuments. Local activists are trying to preserve their names and locations.

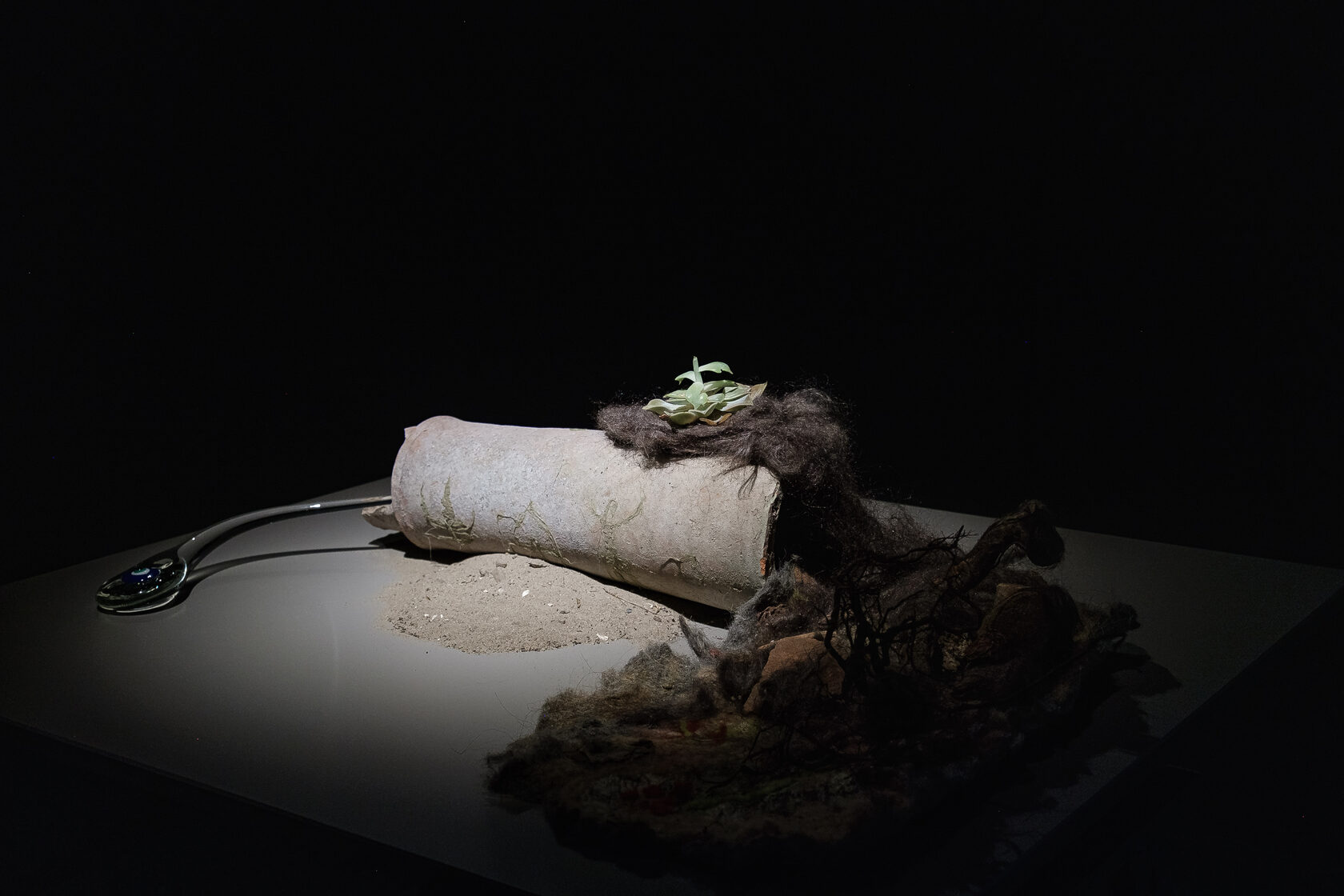

In my installation, I used an artifact—a fragment of an old ceramic water pipe—that I found during my research on water usage culture in Crimea. Drawings made with algae collected from moist rocks reflect the hidden history of the Crimean Tatar people, which has the ability to manifest even over time. Nature, which indigenous people relied on for survival in different territories, becomes an ally in the imagined hope that small hydraulic structures will sprout again on the ruins and fragments of what we have today. The echinodermata succulent, also known as the "stone flower," is planted on Crimean Tatar Muslim graves in the peninsula's arid climate. This flower, as a symbol of growth and vitality, represents an indelible memory for the people.

In my installation, I used an artifact—a fragment of an old ceramic water pipe—that I found during my research on water usage culture in Crimea. Drawings made with algae collected from moist rocks reflect the hidden history of the Crimean Tatar people, which has the ability to manifest even over time. Nature, which indigenous people relied on for survival in different territories, becomes an ally in the imagined hope that small hydraulic structures will sprout again on the ruins and fragments of what we have today. The echinodermata succulent, also known as the "stone flower," is planted on Crimean Tatar Muslim graves in the peninsula's arid climate. This flower, as a symbol of growth and vitality, represents an indelible memory for the people.

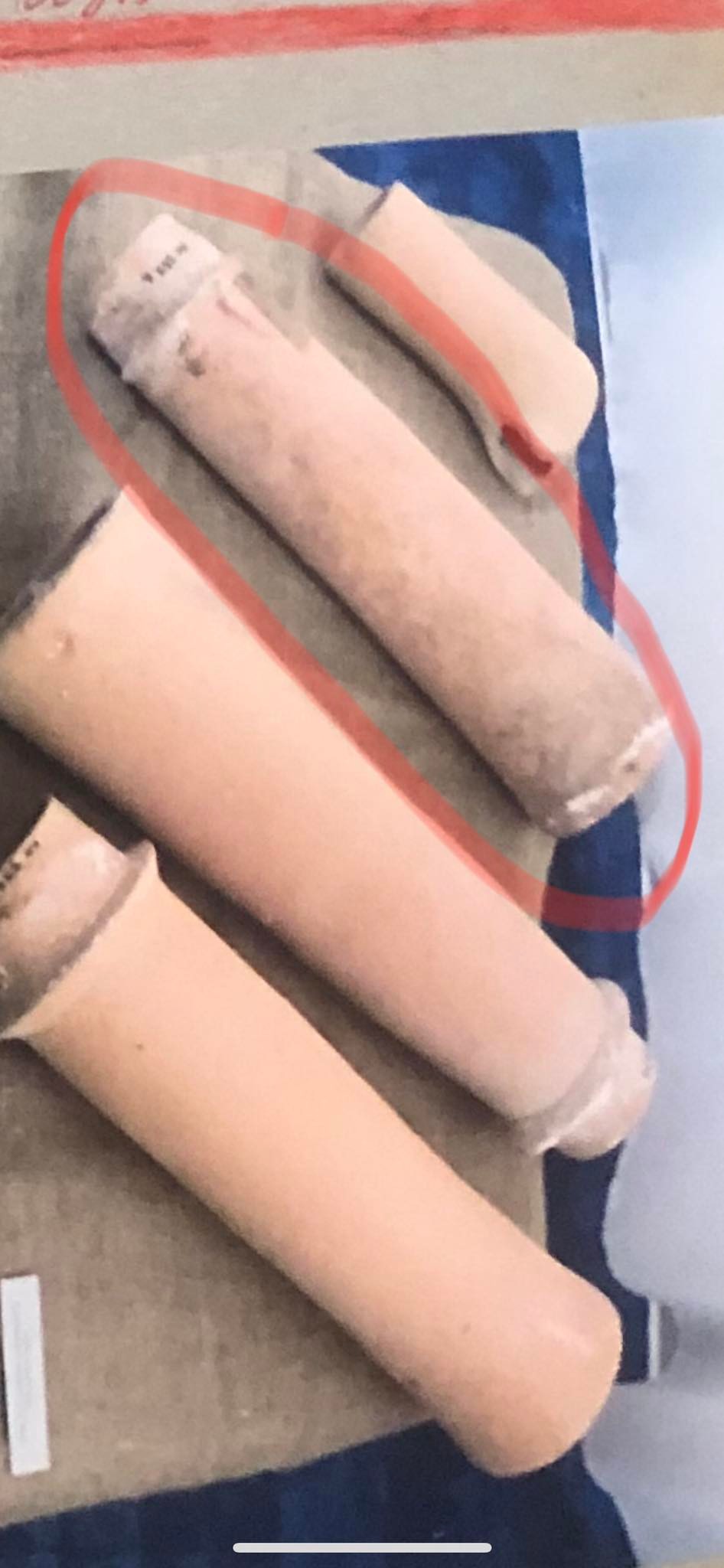

Photo of similar ceramic water pipes from the collection of the Museum of Crimean Tar Culture, Stary Krym, Crimea

A fragment of a ceramic water pipe found during the expedition, 2022

video

2/4

3/4

about the book

I began working on my book about water culture at the outset of my time as a participant in the 1520 Space laboratory at the Garage Museum. My focus was on the study of water resources and water usage among the Crimean Tatars as part of the "Muhammad’s Paradise" research. Although the laboratory's activities were halted in 2022, I managed to encapsulate the results of my project in an artist's book and installation titled "Growing into Paradise," which was exhibited in summer 2023 at the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam.

This book has become my travel journal, capturing the mysteries of water culture in various locations, moments of interaction with water, and the significant details about Crimean Tatar hydraulic structures that I uncovered. I designed it as an old cardboard photo album, a treasured childhood memory. My aunt once created such an album for me, documenting the beginnings of my life and my ancestors' history. This early artistic document sparked my exploration of my own identity.

I created this book for myself, to remember. The theme of water guided me through different cities with water sources—I visited Baikal, immersed myself in the Belaya River in Ufa, and even drank water from the Volga. I discovered abandoned and forgotten fountains in Crimea, once stone-carved springs. Photographs and artifacts collected during my travels were incorporated into the book, with a fragment of a clay drainpipe serving as the foundation for the installation.

This book has become my travel journal, capturing the mysteries of water culture in various locations, moments of interaction with water, and the significant details about Crimean Tatar hydraulic structures that I uncovered. I designed it as an old cardboard photo album, a treasured childhood memory. My aunt once created such an album for me, documenting the beginnings of my life and my ancestors' history. This early artistic document sparked my exploration of my own identity.

I created this book for myself, to remember. The theme of water guided me through different cities with water sources—I visited Baikal, immersed myself in the Belaya River in Ufa, and even drank water from the Volga. I discovered abandoned and forgotten fountains in Crimea, once stone-carved springs. Photographs and artifacts collected during my travels were incorporated into the book, with a fragment of a clay drainpipe serving as the foundation for the installation.

In memory of my great-grandmother Hatche, who knew how to conserve water

4/4

Installation. Ceramic water pipe, wool, wood, algae, echinodermata, glass. 2023

installation images