KANAVA

KANAVA is a long-term research project initiated by SASHAPASHA in 2016. It is focused on the memory and history of the Gulag, the Soviet forced-labor camp system established in 1929.

>

>

>

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

1/3

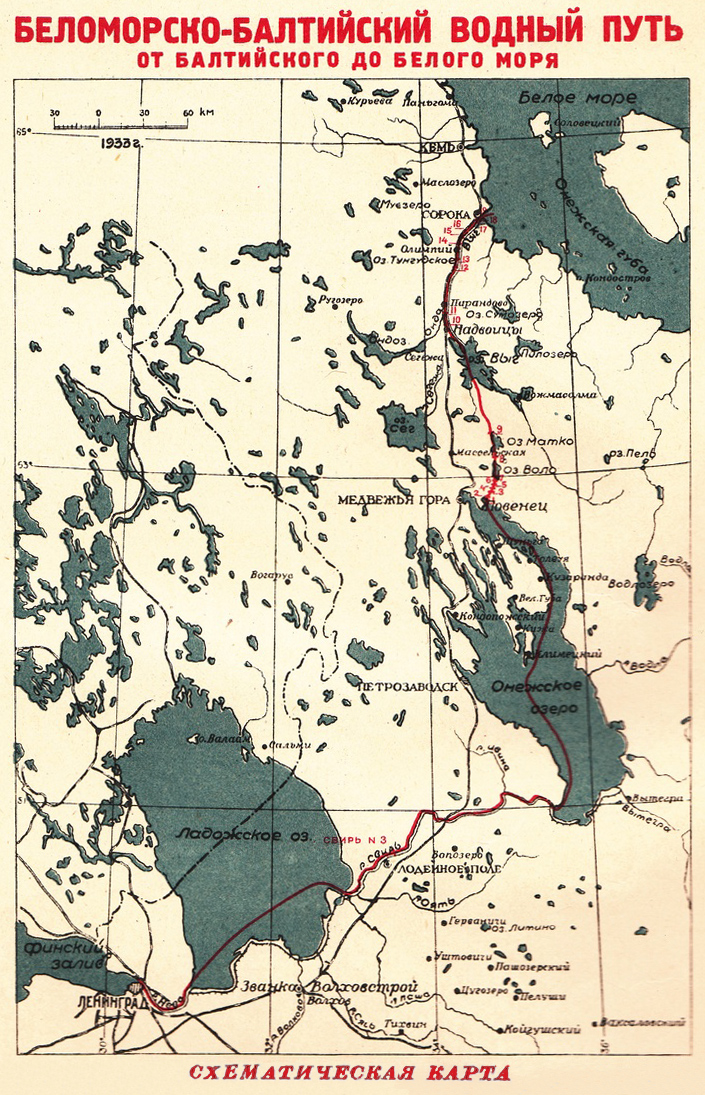

KANAVA is the result of long-term research of the memory about the Gulag (ГУЛАГ) - the Soviet forced-labour camp system implemented in 1929 - that SASHAPASHA began in 2016. The project was named after the White Sea-Baltic canal in northern Karelia that connected the White Sea on the North/West of Russia with the Baltic Sea. The construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal, AKA Belomorkanal, was the very first project of the USSR's forced labour system, later called GULAG. Constructed under the Stalin regime and proclaimed as a tool for “re-forging” the inmates into ‘normal’ Soviet citizens, GULAG was a way to accelerate industrialisation with a small outlay while reinforcing mass repressions of the national minorities.

Finland-based artist duo uses the Finnish word Kanava to highlight that Finns, one of the most significant minorities in Karelia, comprised a large percentage of Gulag victims during the Stalins purge.

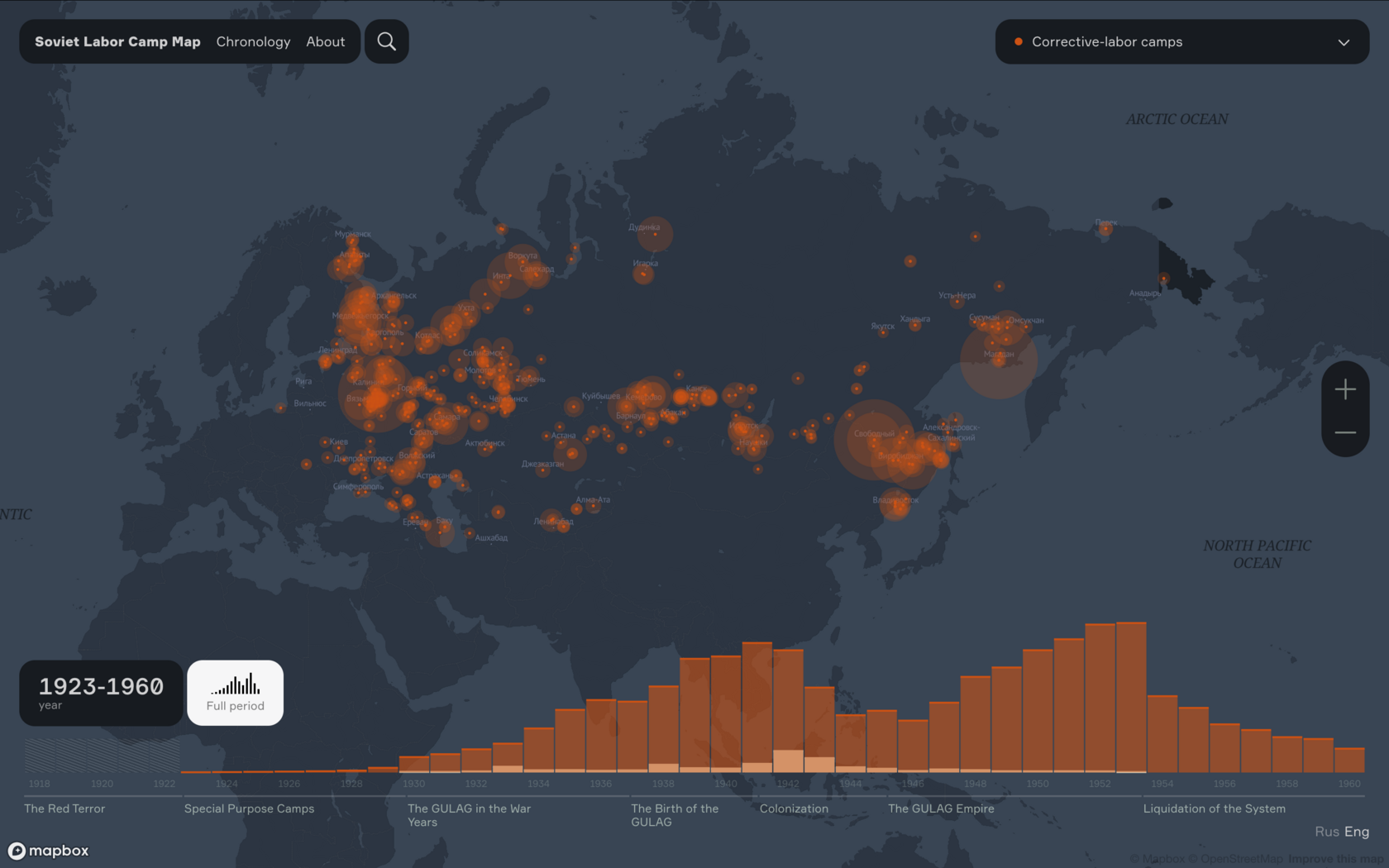

Starting on the shore of Belomorkanal in Karelia, the project unravels into vast territories of the former USSR. Established and tested in Karelia, the GULAG system, like a virus, spreads over the country. The gigantic diagonal line can be drawn over the continent, from Solovetskiye Islands situated on the White Sea in the North-west of Russia to Vladivostok and Magadan on the very East. This line is the centreline of the KANAVA project, surrounded by hundreds of locations - islands of Gulag Archipelago, as writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn called it.

Finland-based artist duo uses the Finnish word Kanava to highlight that Finns, one of the most significant minorities in Karelia, comprised a large percentage of Gulag victims during the Stalins purge.

Starting on the shore of Belomorkanal in Karelia, the project unravels into vast territories of the former USSR. Established and tested in Karelia, the GULAG system, like a virus, spreads over the country. The gigantic diagonal line can be drawn over the continent, from Solovetskiye Islands situated on the White Sea in the North-west of Russia to Vladivostok and Magadan on the very East. This line is the centreline of the KANAVA project, surrounded by hundreds of locations - islands of Gulag Archipelago, as writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn called it.

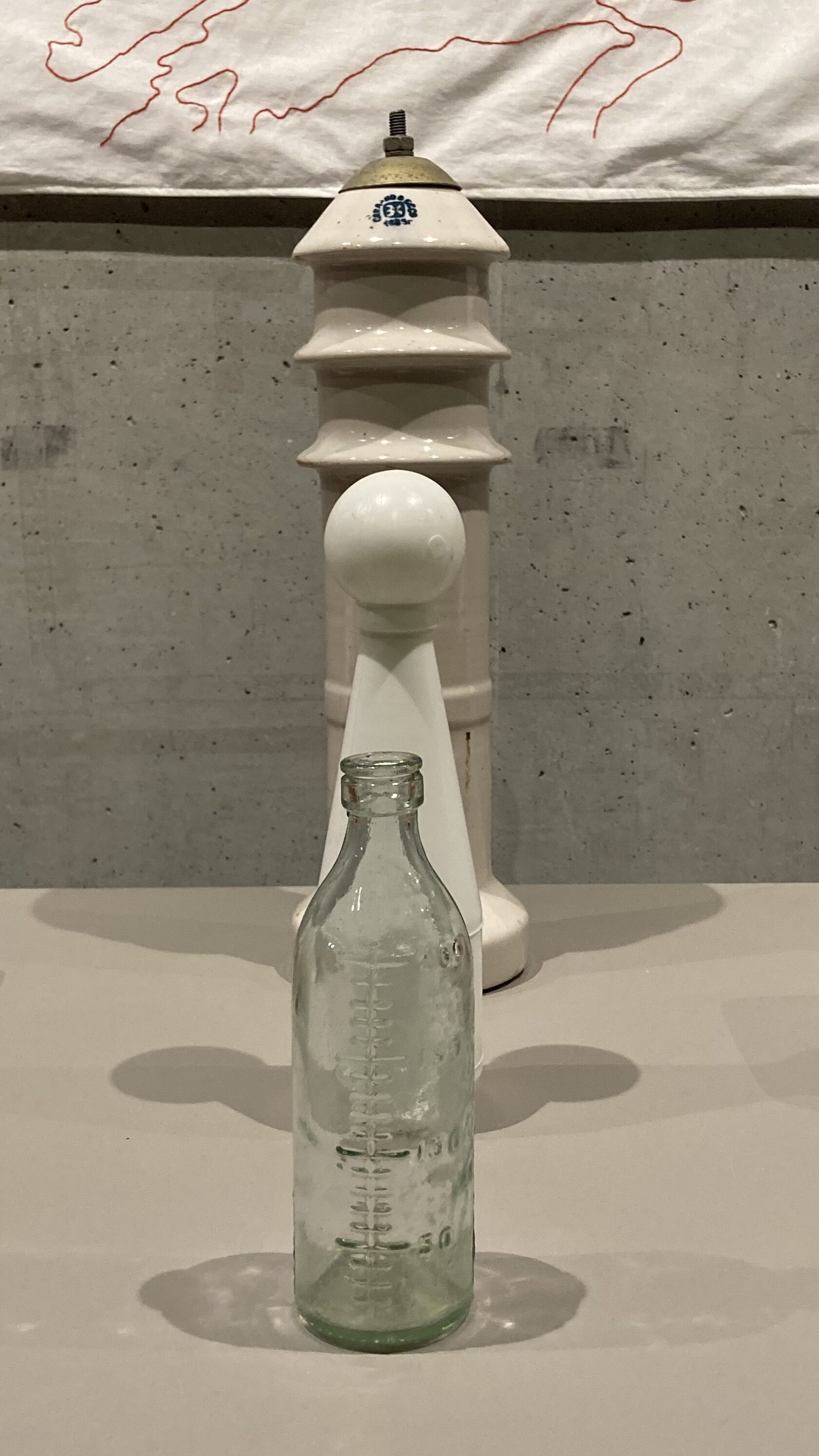

On the long table, visitors can find objects artists collected during expeditions of 2016-2017 in the canal area. The collection draws together reality and fiction, private memories and history. Objects were found in abandoned barracks and campsites, empty workers’ houses from the 30s and abandoned factories, school buildings destroyed by fire and along the railway torn apart for scrap in the 90s. Among them are roasted barbed wires, plastic Soviet toys, school textbooks, a package of gramophone records of Stalin’s speeches, maps and local souvenirs, and a ball of red thread as Ariadne’s tool in a labyrinth of Minotaurus. The red thread in the project links to traditional Karelian embroidery. The navy officer cap decorated with the Berehinia goddess - one of the most common Karelian embroidery is a reminder of the price the region paid for the waterway. Hundreds of villages were fluted to create the canal's watershed. The long embroidery placed on the wall is based on the canal map from the first book about the canal written by 36 Soviet writers, which was banned straight after the first edition, soon after the head of the construction was convicted following the fate of his victims.

Embroidery in the Gulag system was a means of communication between the “zone” and freedom. A message was often embroidered on the rag to make hiding and transmitting information easier. Embroidery in GULAG served as massage in a bottle between the “Gulag Archipelago” islands.

The video installation plays with the most frequently found ‘decorative’ local element - swans hand-carved from rubber tires. The swan was a sacred bird in the beliefs of the northern Karelians. When the rivers and lakes have merged, forming the channel's route, the real birds are replaced by rubber phantoms. Russian writer Mikhail Prishvin has written two books about this region. The Land of Unfrightened Birds, a book celebrating the sanctity of local nature, was written before the revolution. The second one, The Tsar's Road, was written celebrating the White Sea-Baltic Canal. But “Was it worth frightening birds?” the novel's protagonist asks.

Embroidery in the Gulag system was a means of communication between the “zone” and freedom. A message was often embroidered on the rag to make hiding and transmitting information easier. Embroidery in GULAG served as massage in a bottle between the “Gulag Archipelago” islands.

The video installation plays with the most frequently found ‘decorative’ local element - swans hand-carved from rubber tires. The swan was a sacred bird in the beliefs of the northern Karelians. When the rivers and lakes have merged, forming the channel's route, the real birds are replaced by rubber phantoms. Russian writer Mikhail Prishvin has written two books about this region. The Land of Unfrightened Birds, a book celebrating the sanctity of local nature, was written before the revolution. The second one, The Tsar's Road, was written celebrating the White Sea-Baltic Canal. But “Was it worth frightening birds?” the novel's protagonist asks.

Rotterdam, 2023. The process of creating the rubber swan sculpture from car tyres for the Colonial Endurance exhibition in the backyard of the New Institute, Rotterdam. Photo by Sasha Rotts.

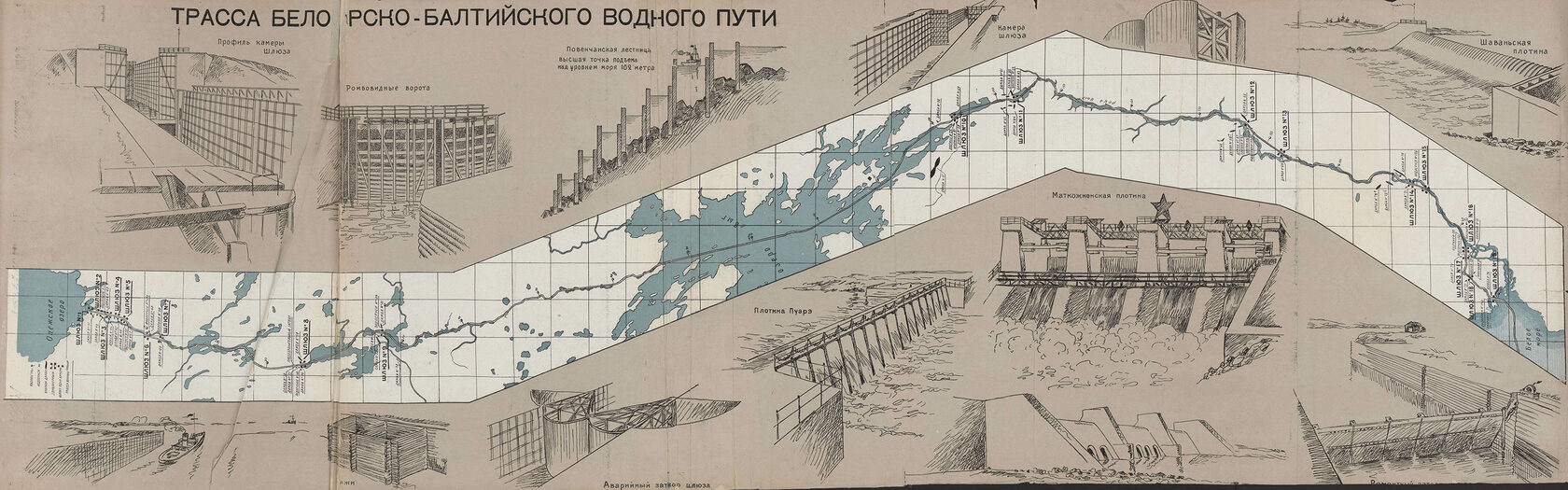

The illustrated map of Belomorkanal from the book GULAG White Sea-Baltic Canal Name Stalin 1934. The volume was edited and compiled by soviet writer Maxim Gorky, with contributions from various other Soviet writers. During the purges of 1937, most OGPU personnel involved in the construction of the White Sea Canal, including Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the OGPU, were either imprisoned or executed. Concurrently, many copies of the volume The I.V. Stalin White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal were destroyed.

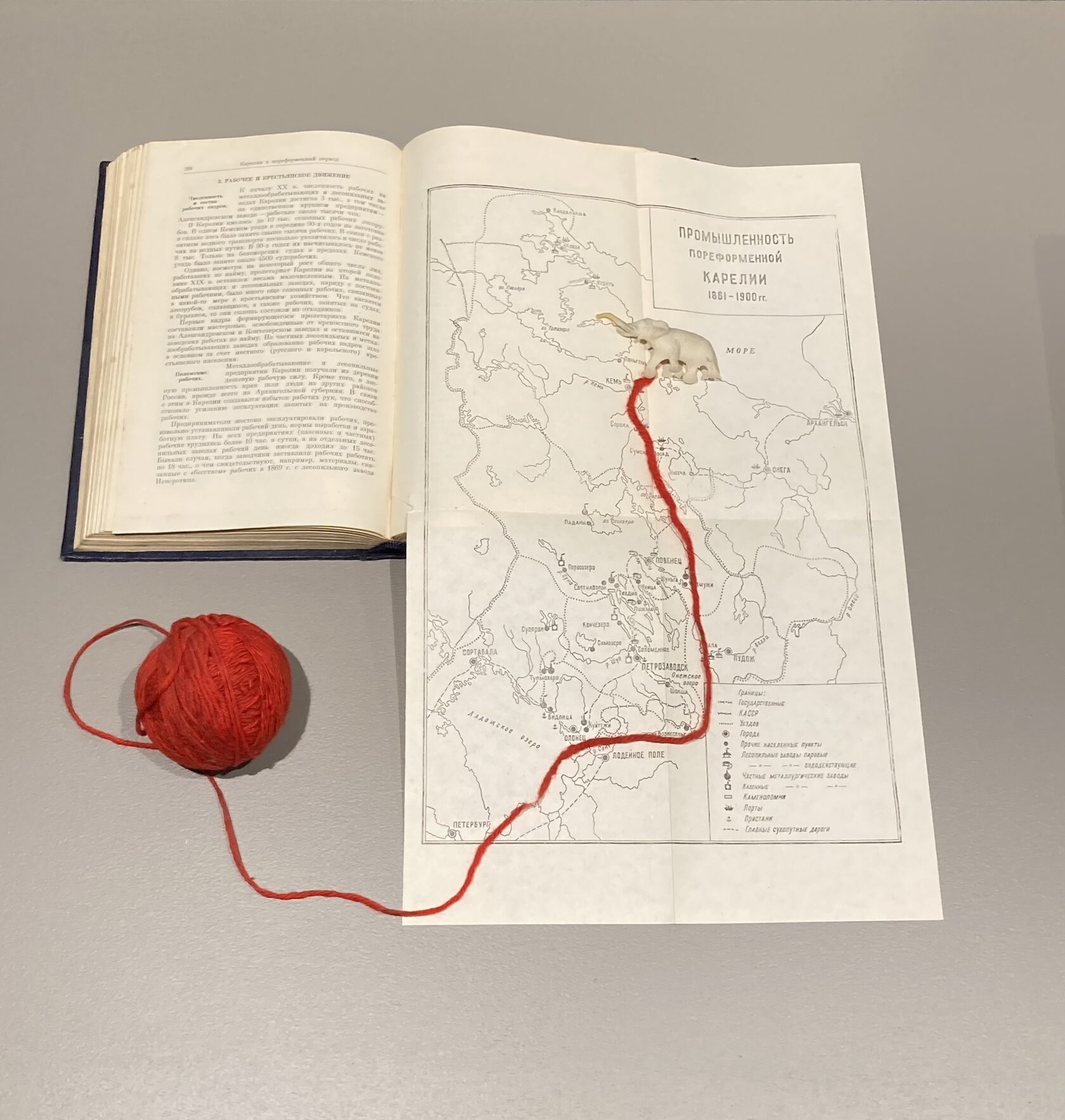

Soviet book on the local history of the Karelian ASSR, featuring a page with a map of the Belomorkanal. The elephant symbolises the Solovetsky Islands special purpose camps, abbreviated as SLON in Russian, which also means "elephant." A ball of red thread traces the canal. Fragment of the SASHAPASHA installation at the Colonial Endurance exhibition. Photo by Pavel Rotts.

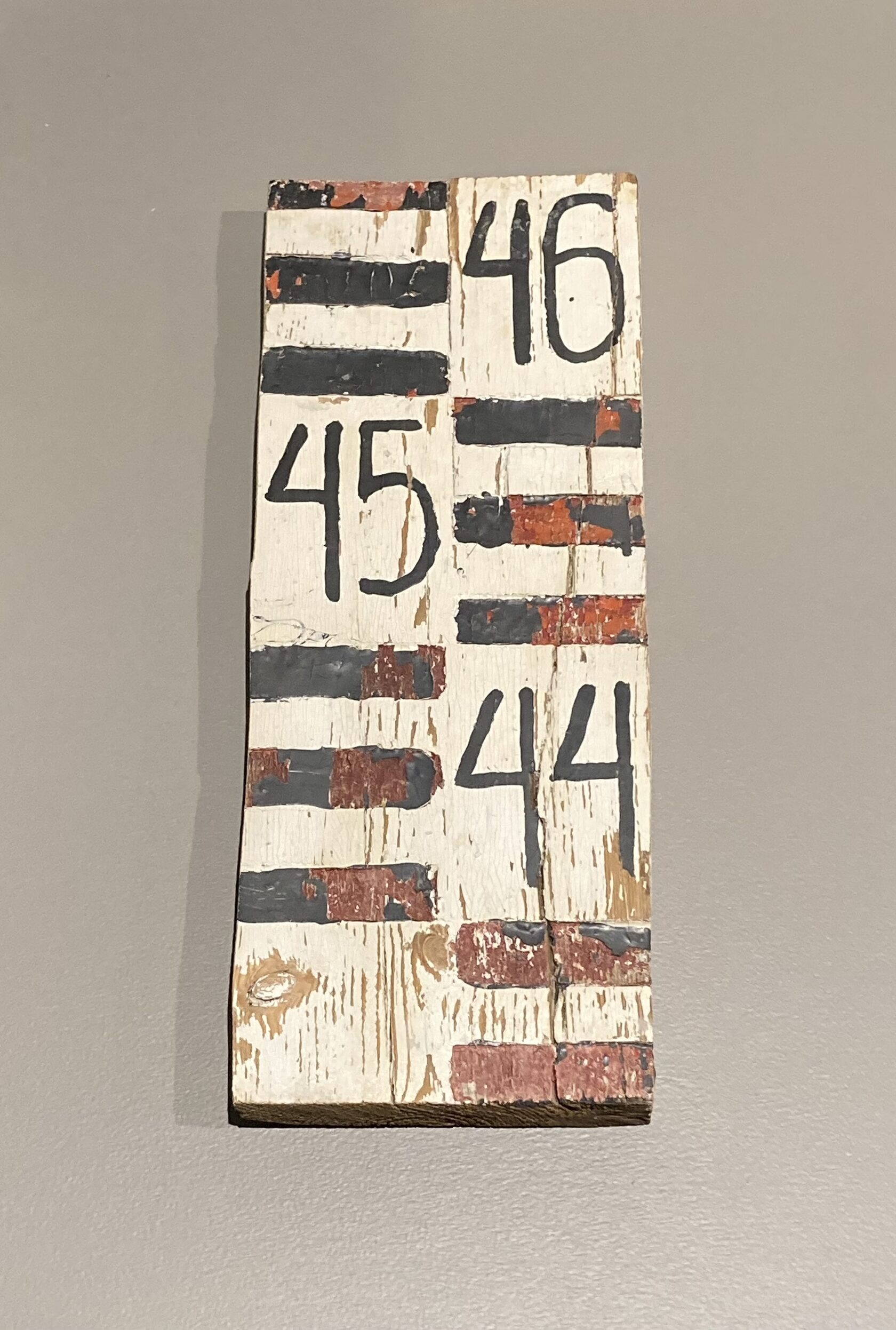

The Water level plate from the 16th gate of Belomorkanal

Objects found in the settlements on 19th-14th canal gates

Soviet tin toy car found in abandoned worker house on 16th gate of Belomorkanal

Navy officer cap with the traditional Karelian embroidery by Sasha Rotts

A flour sieve from Soviet times was found on the 16th gate, and a toy from the 90s was found on the 14th gate of Belomorkanal

A plastic Toy shovel was found in an abandoned building at the second gate of Belomorkanal in Povenets, stones from varicose places along the canal

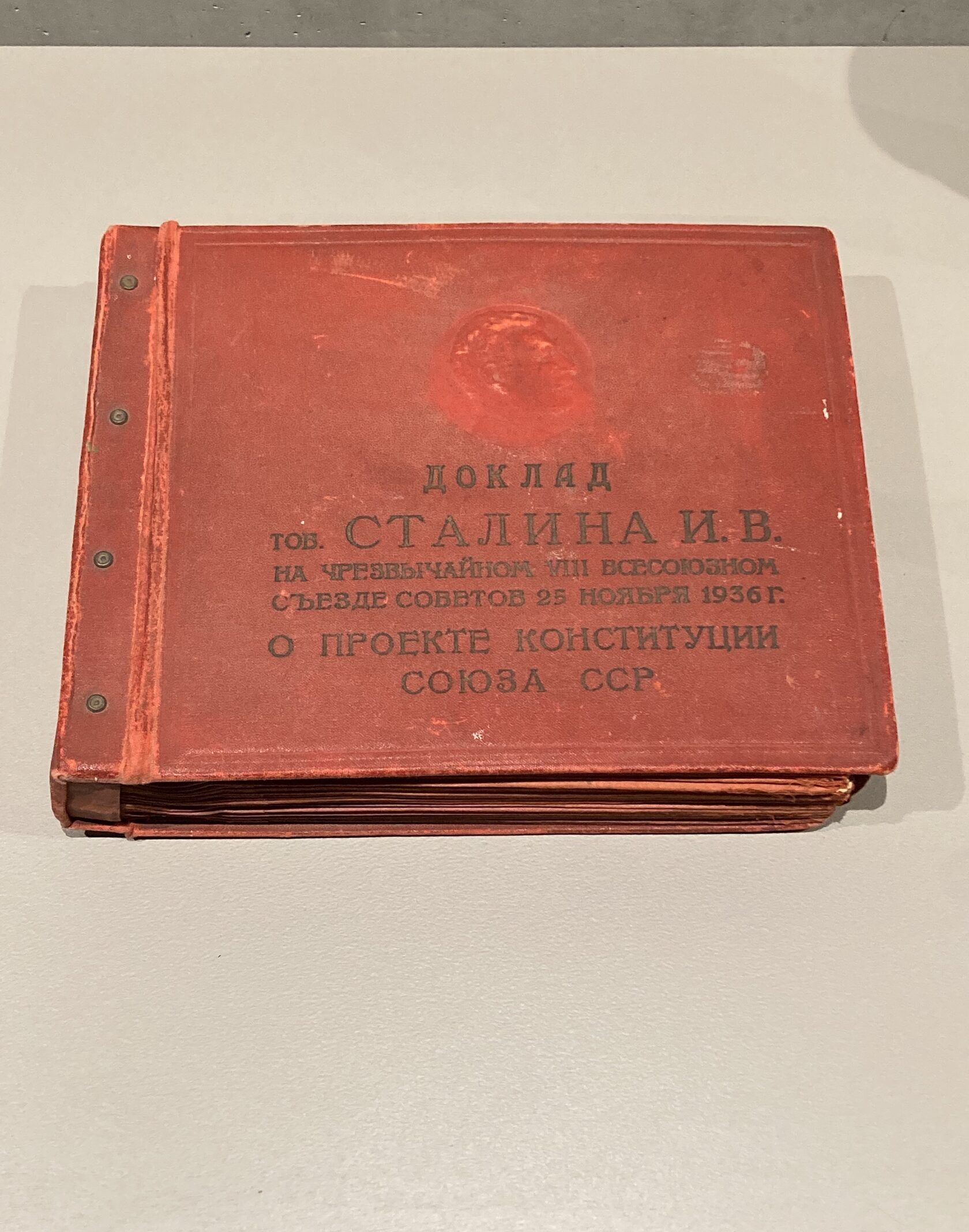

A package of phonograph records with a Joseph Stalin portrait on the cover, “On the Draft Constitution of the U.S.S.R. Report Delivered at the Extraordinary Eighth Congress of Soviets of the U.S.S.R.” field with soviet pop music gramophone records was found in abandoned building Medvezhegorsk where teh administration of the canal was situated in 30s

The book about fishing from an abandoned building in Medvezhegorsk and a lid from Soviet canned sardines sourced from a former cannery in Belomorsk built by GULAG prisoners

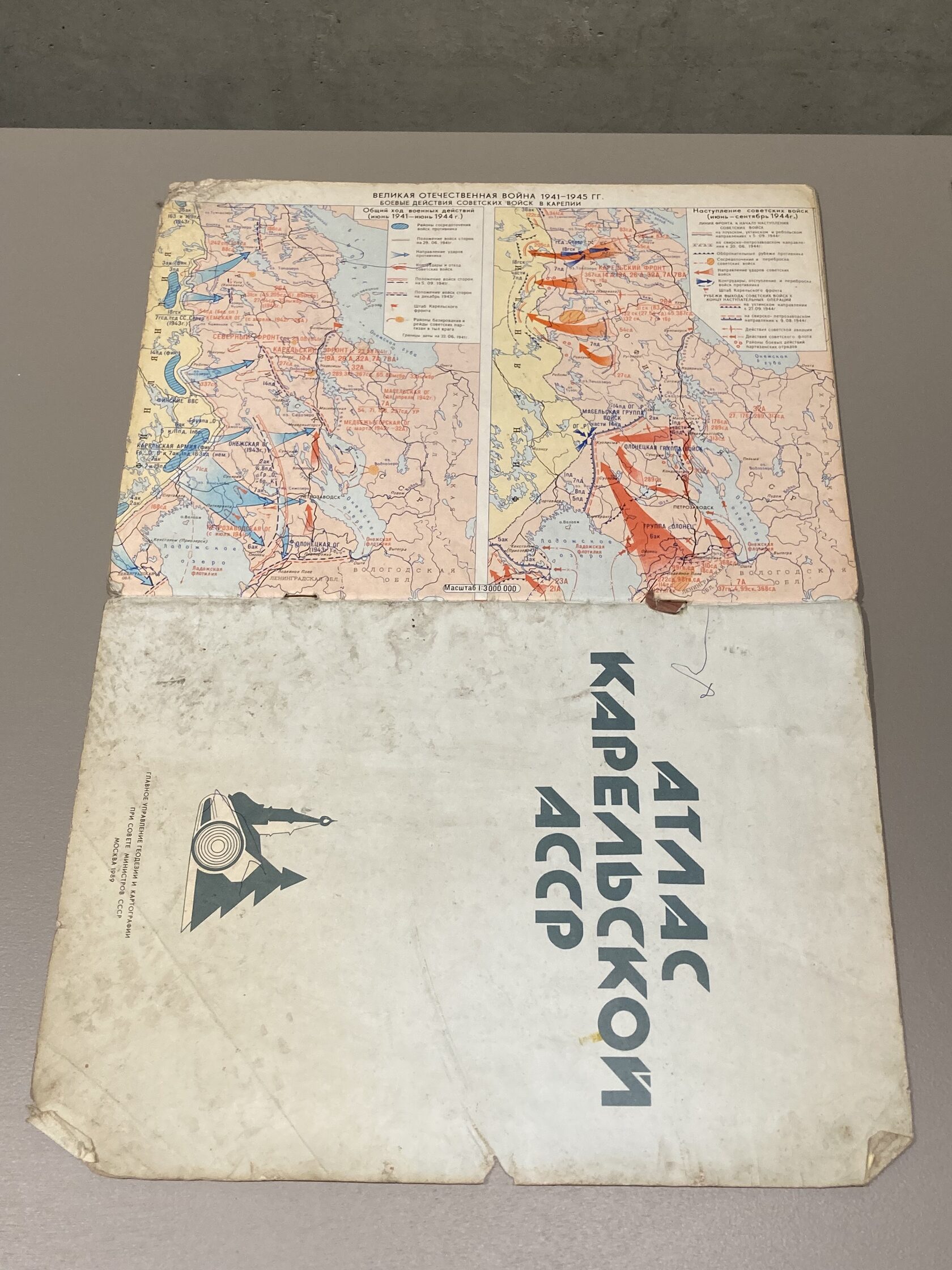

The map of the Karelian ASSR, discovered in an abandoned school in Medvezhegorsk, is opened to the page depicting the battles of WWII in the Belomorkanal area

KANAVA project's timeline and geography

2/3

Tested with the White Sea-Baltic Canal in Soviet Karelia, the GULAG system spreads like a virus over the country. A gigantic diagonal line can be drawn over the continent, from Solovetskiye Islands on the White Sea northwest of Russia to Vladivostok in the southeast. This line is the centreline of the KANAVA project, surrounded by hundreds of Gulag Archipelago islands, as former GULAG inmate and world-famous writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn called it.

This conditional diagonal line can be drawn connecting these points of the project:

White Sea-Baltic waterway from the Baltic to the White Sea. Schematic map 1933

Solovki

Belomorkanal

Archangelsk

Nizhny Novgorod

Norilsk

Vladivostok

Screnshot from the website with the map of the Soviet Forced Labor Camps acress the teritory of USSR

● Solovki

SASHAPASHA’s journey within the KANAVA project began in 2016 on Solovetsky Island, where the GULAG was officially established in the 1930s. Their first trip was self-organized, taking them to the northern part of the canal. There, they visited sites tied to personal history: Pavel’s grandfather spent his childhood in the region, and his great-grandmother worked on the 15th gate of the canal in the village of Sosnovets. Using an old mini DV camera, the duo documented their trip and produced a short documentary film. They also gathered information and collected objects, intending to return the following year.

SASHAPASHA’s journey within the KANAVA project began in 2016 on Solovetsky Island, where the GULAG was officially established in the 1930s. Their first trip was self-organized, taking them to the northern part of the canal. There, they visited sites tied to personal history: Pavel’s grandfather spent his childhood in the region, and his great-grandmother worked on the 15th gate of the canal in the village of Sosnovets. Using an old mini DV camera, the duo documented their trip and produced a short documentary film. They also gathered information and collected objects, intending to return the following year.

Solovetsky Islands, 2016. Solovki State Historical, Architectural, and Natural Museum-Reserve. A fragment of the permanent exhibition on the Solovetsky special purpose camps (1920–1939), located in the historic barracks building of the Administration of the Solovetsky Special Purpose Camps (USLON), constructed in 1929. Photo by Pavel Rotts.

Sosnovets 2016, The banks of the canal near the village of Sosnovets, 14-15th gates of Belomorkanal, photo by Pavel Rotts.

Vygostrov 2016, Canal maintenance Workers houses in the village at the 16th gate of the Belomorkanal. photo by Pavel Rotts

Vygostrov 2016, Vygostrovskaya Ges, a part of Belomorkanal infrastructure at the 16th gate of the Belomorkanal. photo by Pavel Rotts

● Belomorkanal

In the summer of 2017, they returned to the region. Starting from Belomorsk, where the 18th gate of the White Sea-Baltic Canal (or Belomorkanal, as it’s known in Russia) connects the canal to the White Sea, they traveled along the canal, visiting former campsites, filming, meeting locals, visiting museums, and collecting objects. These objects would later form the foundation for SASHAPASHA’s Belomorkanal Museum installation.

That same year, a significant campaign to rewrite the history of the GULAG began in Russia, leading to the repression of those investigating the truth. The central figure and first victim of this new wave of repression was Yuri Dmitriev, who had uncovered a mass grave in the place calle Sandarmokh containing thousands of victims from Stalin’s “Great Purge” of 1937 after years of searching the pine forests around the Belomorkanal. Since then, SASHAPASHA’s project has evolved in parallel with what became known as the Dmitriev Affair. Though never directly linked to it, the project has consistently carried the contemporary struggle for historical truth as part of its context.

In the summer of 2017, they returned to the region. Starting from Belomorsk, where the 18th gate of the White Sea-Baltic Canal (or Belomorkanal, as it’s known in Russia) connects the canal to the White Sea, they traveled along the canal, visiting former campsites, filming, meeting locals, visiting museums, and collecting objects. These objects would later form the foundation for SASHAPASHA’s Belomorkanal Museum installation.

That same year, a significant campaign to rewrite the history of the GULAG began in Russia, leading to the repression of those investigating the truth. The central figure and first victim of this new wave of repression was Yuri Dmitriev, who had uncovered a mass grave in the place calle Sandarmokh containing thousands of victims from Stalin’s “Great Purge” of 1937 after years of searching the pine forests around the Belomorkanal. Since then, SASHAPASHA’s project has evolved in parallel with what became known as the Dmitriev Affair. Though never directly linked to it, the project has consistently carried the contemporary struggle for historical truth as part of its context.

Sosnovets, 2016. Rubber swan folk sculptures in the Sosnovets settlement near the 14th and 15th gates of the Belomorkanal. Photo by Pavel Rotts.

SASHAPASHA 2020, Pavel Rotts, Sasha Rotts, Wild Swans, Installation, car tires carving, metal wire, video projection, KANAVA V, Exhibition Laboratory, Helsinki, Finland

SASHAPASHA 2020, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts, Belomorkanal Museum, objects found on the shores of White Sea-Baltic Canal, shelves, 2020 KANAVA V, Exhibition Lab- oratory, Helsinki, Finland, Photo by Pavel Rotts

Sandarmokh 2017. Sandarmokh Mass Grave Memorial, discovered by Yuri Dmitriev in the 1990s. The monument, bearing the words "People, don't kill each other," was installed on the first anniversary of the site’s discovery in 1998. Photo by Pavel Rotts

● Archangelsk

In 2018, they joined an ethnographic expedition to the Arkhangelsk region, organized by The Propp Centre for Humanities-Based Research in the Sphere of Traditional Culture, to visit the northern labor camps in Arkhangelsk, Severodvinsk, and Pinega. This region housed many timber camps where inmates were tasked with cutting and rafting wood. The artist duo found a surprisingly thorough representation of the local GULAG history in a nearby museum. They also met with Galina Danilova, a local historian specializing in GULAG research. Several quotes from her book Soviet Period History Pages were incorporated into SASHAPASHA’s Penal Labour installation later that year.

In 2018, they joined an ethnographic expedition to the Arkhangelsk region, organized by The Propp Centre for Humanities-Based Research in the Sphere of Traditional Culture, to visit the northern labor camps in Arkhangelsk, Severodvinsk, and Pinega. This region housed many timber camps where inmates were tasked with cutting and rafting wood. The artist duo found a surprisingly thorough representation of the local GULAG history in a nearby museum. They also met with Galina Danilova, a local historian specializing in GULAG research. Several quotes from her book Soviet Period History Pages were incorporated into SASHAPASHA’s Penal Labour installation later that year.

left. Pinega, 2018. Memorial to Poles exiled to Pinega, who worked in the region’s timber camps. The engraving reads: “In memory of the Poles exiled to Pinega district who remained in this land forever, in honor of the good people—Russians who provided assistance in difficult times to their community, thanks to whom they were given the opportunity to return to their homeland.” photo by Pavel Rotts

right. Pinega, 2018. Memorial to all victims of political repressions. The engraving reads: “To those who died during the years of the Red and White terror, those who suffered during the dispossession of the kulaks, to special settlers from other regions of the country, citizens deported from the territory of Poland, Estonians mobilized into labor columns and prisoners of Kuloylag and other forced labor camps.” photo by Pavel Rotts

right. Pinega, 2018. Memorial to all victims of political repressions. The engraving reads: “To those who died during the years of the Red and White terror, those who suffered during the dispossession of the kulaks, to special settlers from other regions of the country, citizens deported from the territory of Poland, Estonians mobilized into labor columns and prisoners of Kuloylag and other forced labor camps.” photo by Pavel Rotts

Pinega, 2018. A wooden apartment building in the village of Pinega with the Soviet slogan: “Comrades! Strive for a settlement with a high culture of living.” Photo by Pavel Rotts

● Nizhny Novgorod

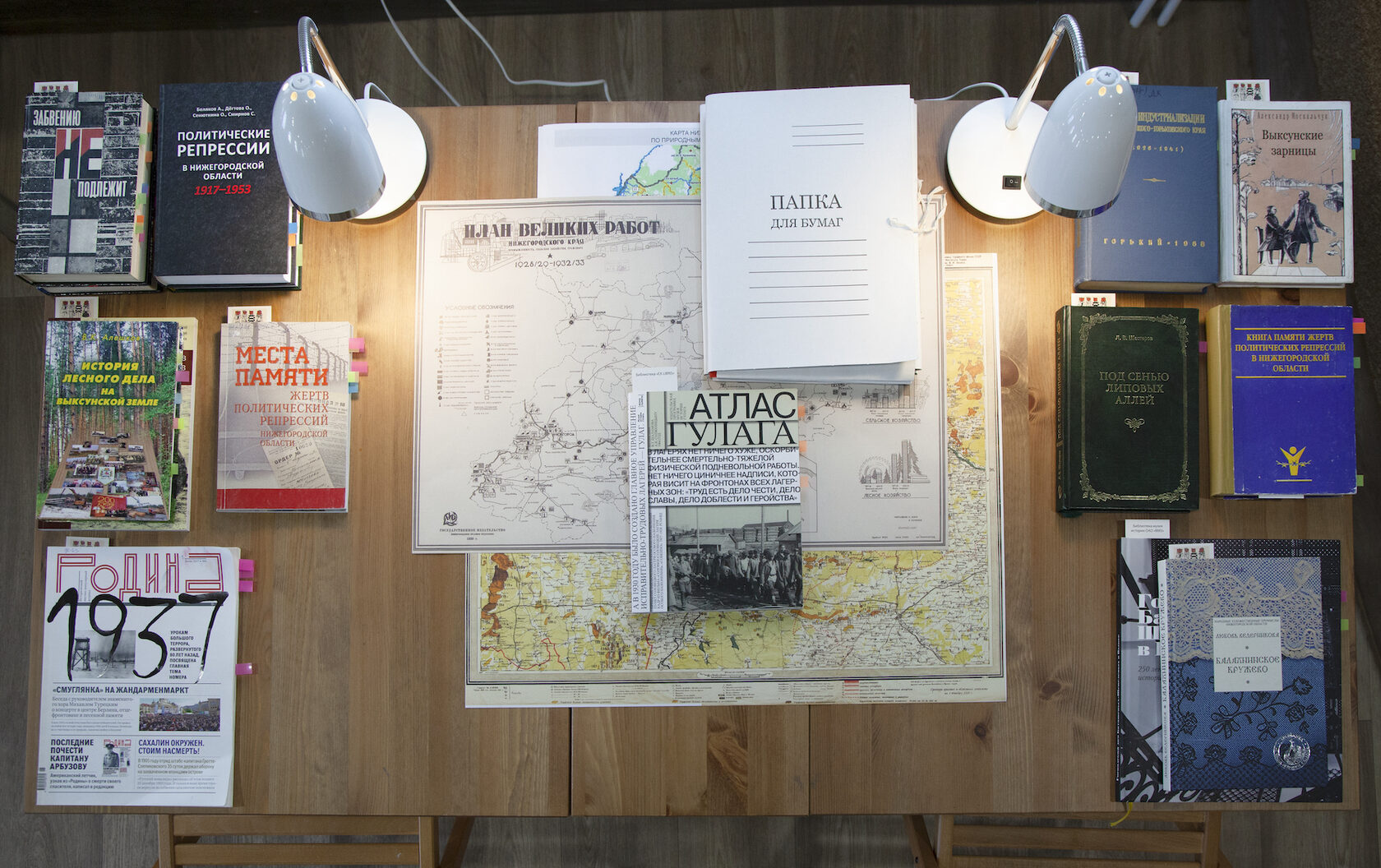

In 2019, SASHAPASHA spent a month at the VYKSA Art Residency in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, where they researched the darker side of the local metal industry, specifically peat mining, which was once part of the GULAG system. This research culminated in the Peat and Lace exhibition at the local museum, exploring the connections between iron casting, lace making, peat mining, and forced labor. A particular focus of the exhibition was the environmental consequences of peat mining, especially its role in the massive forest fires that ravaged the region in 2010. A four-square-meter embroidery depicting a map of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast’s GULAG camps, juxtaposed with a map of the forest fires, was displayed alongside a research table. The table featured literature, periodical press on the topic, and video footage from local swamps where peat was once extracted by prisoners during Stalin’s industrialization.

In 2019, SASHAPASHA spent a month at the VYKSA Art Residency in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, where they researched the darker side of the local metal industry, specifically peat mining, which was once part of the GULAG system. This research culminated in the Peat and Lace exhibition at the local museum, exploring the connections between iron casting, lace making, peat mining, and forced labor. A particular focus of the exhibition was the environmental consequences of peat mining, especially its role in the massive forest fires that ravaged the region in 2010. A four-square-meter embroidery depicting a map of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast’s GULAG camps, juxtaposed with a map of the forest fires, was displayed alongside a research table. The table featured literature, periodical press on the topic, and video footage from local swamps where peat was once extracted by prisoners during Stalin’s industrialization.

SASHAPASHA 2019, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts; Interactive embroidered map of Gorkovskiy Gulag; 300 x 300cm.; fabric, laces, electroconductive yarn, embroidery, LED lights, microcontroller, power supply, VYKSA artist residency, Vyksa, Russia, photo by Pavel Rotts

SASHAPASHA 2019, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts; Sasha Rotts is embroidering on the former peat deposit near Vyksa,VYKSA artist residency, Vyksa, Russia, photo by Pavel Rotts

Peat and Lace, SASHAPASHA 2019, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts; Research Table in the local library, interactive installation, table, chairs, lamps, printed materials, books from the local libraries on the topic of GULAG, industrialization, wildfires and peat extraction, VYKSA artist residency, Vyksa, Russia, photo by Pavel Rotts

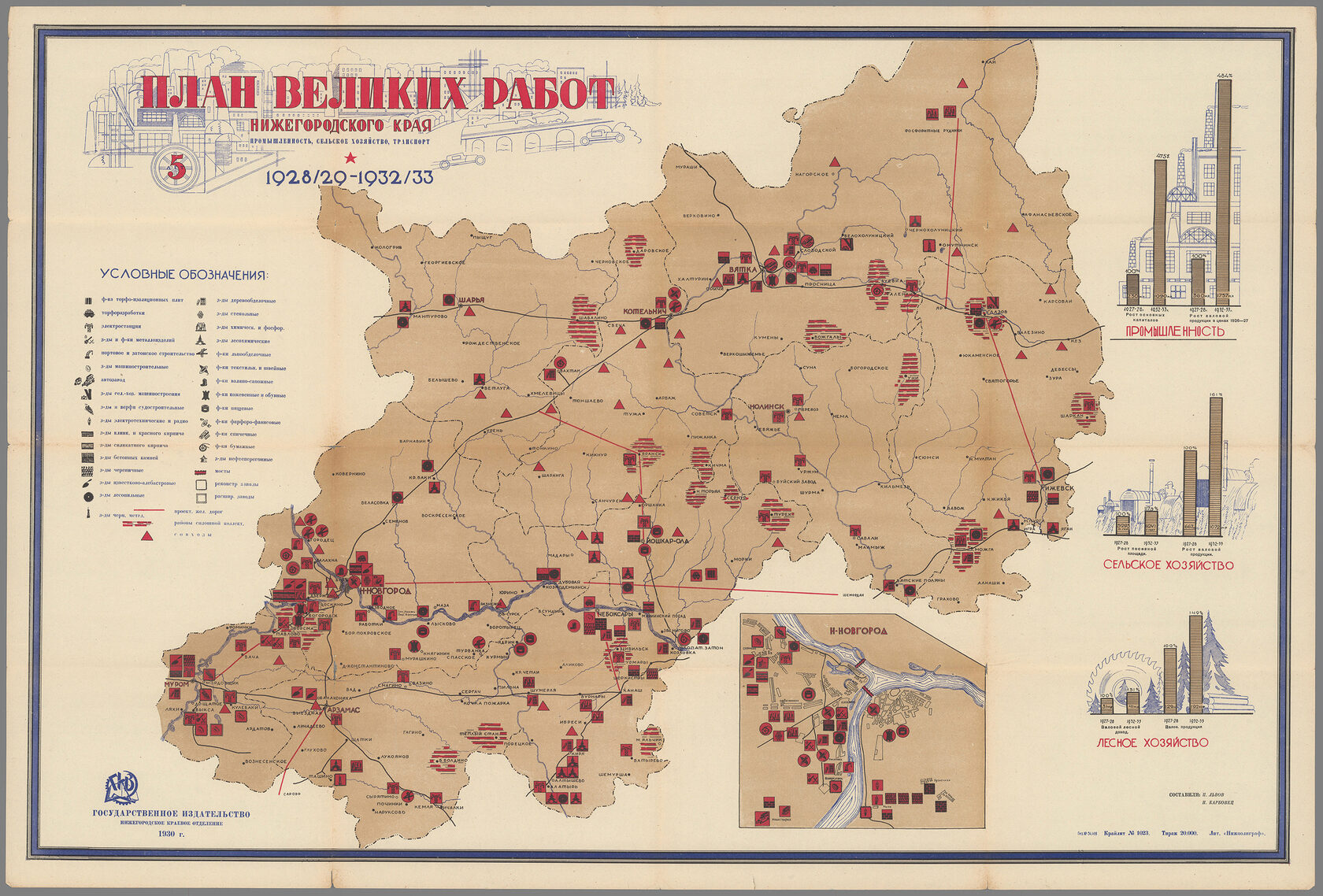

1930, The map for the great working plan for the Nizhny Novgorod region. Industry, agriculture, transport. 1928/29 - 1932/33, State Nizhny Novgorod Publishing House of the USSR

● Norilsk

In 2020, the duo visited Norilsk, an industrial city located above the Arctic Circle in Siberia's Taimyr region, known as one of the most polluted cities in the world. It was constructed by GULAG prisoners on permafrost under inhumane conditions, and one of the largest forced labor camps there specialized in the excavation of copper and nickel—a mining operation that continues to this day.

The project they developed in Norilsk draws inspiration from the Letters to Comrades of the Future, a phenomenon widely spread during the Soviet era. Many time capsules containing letters to “Komsomol members of the 21st century” were sealed during the USSR's existence. The dark side of this optimism is revealed through letters written by GULAG prisoners, the true builders of Communism, addressed to future generations. This contrast between a linear, optimistic view of progress and the grim reality of forced labor highlights how progress can be an ambiguous process, capable of leading to collapse.

In 2020, the duo visited Norilsk, an industrial city located above the Arctic Circle in Siberia's Taimyr region, known as one of the most polluted cities in the world. It was constructed by GULAG prisoners on permafrost under inhumane conditions, and one of the largest forced labor camps there specialized in the excavation of copper and nickel—a mining operation that continues to this day.

The project they developed in Norilsk draws inspiration from the Letters to Comrades of the Future, a phenomenon widely spread during the Soviet era. Many time capsules containing letters to “Komsomol members of the 21st century” were sealed during the USSR's existence. The dark side of this optimism is revealed through letters written by GULAG prisoners, the true builders of Communism, addressed to future generations. This contrast between a linear, optimistic view of progress and the grim reality of forced labor highlights how progress can be an ambiguous process, capable of leading to collapse.

Letters to the Past, SASHAPASHA 2020, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts; a tapestry made of materials donated by Norisk residents, embroidery by Sasha Rotts, PolArt residency, Norilsk, Russia, photo by Pavel Rotts

● Vladivostok

The furthest points of SASHAPASHA's journey within this project were Vladivostok and Nakhodka in the Russian Far East. These locations served as major transition camps for GULAG prisoners, who were shipped to the northern camps of Magadan. Throughout Russia, from Karelia to the Far East, we frequently encountered swans carved from car tires during our first trip to Karelia. In Vladivostok, countless tires filled courtyards and streets, transformed by local inhabitants into rows of flower beds and garden sculptures—swans, cheburashkas, tumblers, and more.

Tires also serve as fuel for protests in urban environments, burned by demonstrators to protect themselves from the police. Metaphorically speaking, the city of Vladivostok is filled with makeshift explosives crafted from this material. In contrast, there has been an effort to channel this energy through peaceful means, exemplified by the creation of folk sculptures from car tires.

A pop-up exhibition at Zarya Residency in Vladivostok showcased burned tire swans and embroidered navy caps. The embroidery hoops resemble officer caps, while sea maps embroidered on the caps represent the maritime routes taken by prisoners from Vladivostok to Magadan. Additionally, black and white circles form a pattern reminiscent of the stones used in the game of ‘Go,’ a game of territorial conquest that reflects the complex colonial history of the Russian Far East and Russia’s geopolitical ambitions.

The furthest points of SASHAPASHA's journey within this project were Vladivostok and Nakhodka in the Russian Far East. These locations served as major transition camps for GULAG prisoners, who were shipped to the northern camps of Magadan. Throughout Russia, from Karelia to the Far East, we frequently encountered swans carved from car tires during our first trip to Karelia. In Vladivostok, countless tires filled courtyards and streets, transformed by local inhabitants into rows of flower beds and garden sculptures—swans, cheburashkas, tumblers, and more.

Tires also serve as fuel for protests in urban environments, burned by demonstrators to protect themselves from the police. Metaphorically speaking, the city of Vladivostok is filled with makeshift explosives crafted from this material. In contrast, there has been an effort to channel this energy through peaceful means, exemplified by the creation of folk sculptures from car tires.

A pop-up exhibition at Zarya Residency in Vladivostok showcased burned tire swans and embroidered navy caps. The embroidery hoops resemble officer caps, while sea maps embroidered on the caps represent the maritime routes taken by prisoners from Vladivostok to Magadan. Additionally, black and white circles form a pattern reminiscent of the stones used in the game of ‘Go,’ a game of territorial conquest that reflects the complex colonial history of the Russian Far East and Russia’s geopolitical ambitions.

Burning Swan, SASHAPASHA 2018, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts, happening, car tyres, Jet-Lag Inmates, Zarya artist residency, Vladivostok, Russia, 2018, photo by Rada Smolianskaja

SASHAPASHA 2018, Sasha Rotts, Pavel Rotts, Go, naval officer’s caps with embroidery depicting a fragments of the Nautical Charts of Japan Sea, Jet-lag Imates, Zarya artist residency, Vladivostok, Russia

3/3

Installation. Embroidery on canvas, 1000 x 75cm, embroidery on navy cap, 30x30cm. Found objects, variable sizes. Video, 10’48’’. Sculptures made of tyres, metal wire. 2016–2023

installation images