DEAD RIVER

>

>

>

Over the course of the early 20th century and culminating in the 1950s, commercial trade on the Rhone River necessitated the construction of canals, flood dikes, the establishment of nuclear power plants and chemical industries. The installation of this infrastructure transformed the once powerful and untamed river into a hydraulic object, complicating any strict distinctions between nature and technology.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

1/4

Artist Background

The central question within my artistic practice is how to document landscapes that are no longer visible? The places I’m interested in range from artificial islands to the endless North Sea, and reflect often on how energy production has shaped our landscape.

For example,I immersed myself in the industrial landscape of the North Sea by sailing with maintenance ships and speaking with offshore employees. The landscape takes shape by means of films, prints, sound and texts in which the atmosphere and experience of these places is captured.

Background

About Dead river, a portrait of the river Rhône - a technical landscape becoming undone.

In the 1950s, the Rhône River was declared dead. With the development of hydroelectricity, the river changed drastically in post-war France. New canals took over the old river, dikes were built against flooding, the river was slowly dammed in the name of science and technology. Furthermore, with its fast flow and cool temperatures, the Rhône provided an ideal setting for the development of several nuclear power plants and chemical industry sites. The river became a hydraulic object, the boundaries between nature and technology slowly blurred.

The river – once the symbol of an uncontrollable force – had been conquered, but how would the river best describe itself? Inspired by Bruno Latour's The Parliament of Things, in which the philosopher argues that laws and politics should not be centered only around people, but should respond to all things and life forms, I examined the Rhône from an animistic point of view.

With a fast current, the Rhône originates in the glaciers of Switzerland, meandering to the south of France and ending in the Mediterranean Sea. Along the way, her waters absorb chemicals in the Rhône valley: sediment-carried fluoroalkyl (PFAS), radionuclides (radioactive material), plastic waste and pesticides. The sediment of the Rhône acts as a preservative; Roman artifacts over 2000 years old are still found there. This silt became a symbol of the river’s power and its hidden history.

I tried to imagine what it’s like to be a fast-flowing river, slowly filling with Anthropocene-era artifacts over a 600 kilometer stretch. A landscape steeped in chemical waste, that’s slowly disappearing due to climate change.

The central question within my artistic practice is how to document landscapes that are no longer visible? The places I’m interested in range from artificial islands to the endless North Sea, and reflect often on how energy production has shaped our landscape.

For example,I immersed myself in the industrial landscape of the North Sea by sailing with maintenance ships and speaking with offshore employees. The landscape takes shape by means of films, prints, sound and texts in which the atmosphere and experience of these places is captured.

Background

About Dead river, a portrait of the river Rhône - a technical landscape becoming undone.

In the 1950s, the Rhône River was declared dead. With the development of hydroelectricity, the river changed drastically in post-war France. New canals took over the old river, dikes were built against flooding, the river was slowly dammed in the name of science and technology. Furthermore, with its fast flow and cool temperatures, the Rhône provided an ideal setting for the development of several nuclear power plants and chemical industry sites. The river became a hydraulic object, the boundaries between nature and technology slowly blurred.

The river – once the symbol of an uncontrollable force – had been conquered, but how would the river best describe itself? Inspired by Bruno Latour's The Parliament of Things, in which the philosopher argues that laws and politics should not be centered only around people, but should respond to all things and life forms, I examined the Rhône from an animistic point of view.

With a fast current, the Rhône originates in the glaciers of Switzerland, meandering to the south of France and ending in the Mediterranean Sea. Along the way, her waters absorb chemicals in the Rhône valley: sediment-carried fluoroalkyl (PFAS), radionuclides (radioactive material), plastic waste and pesticides. The sediment of the Rhône acts as a preservative; Roman artifacts over 2000 years old are still found there. This silt became a symbol of the river’s power and its hidden history.

I tried to imagine what it’s like to be a fast-flowing river, slowly filling with Anthropocene-era artifacts over a 600 kilometer stretch. A landscape steeped in chemical waste, that’s slowly disappearing due to climate change.

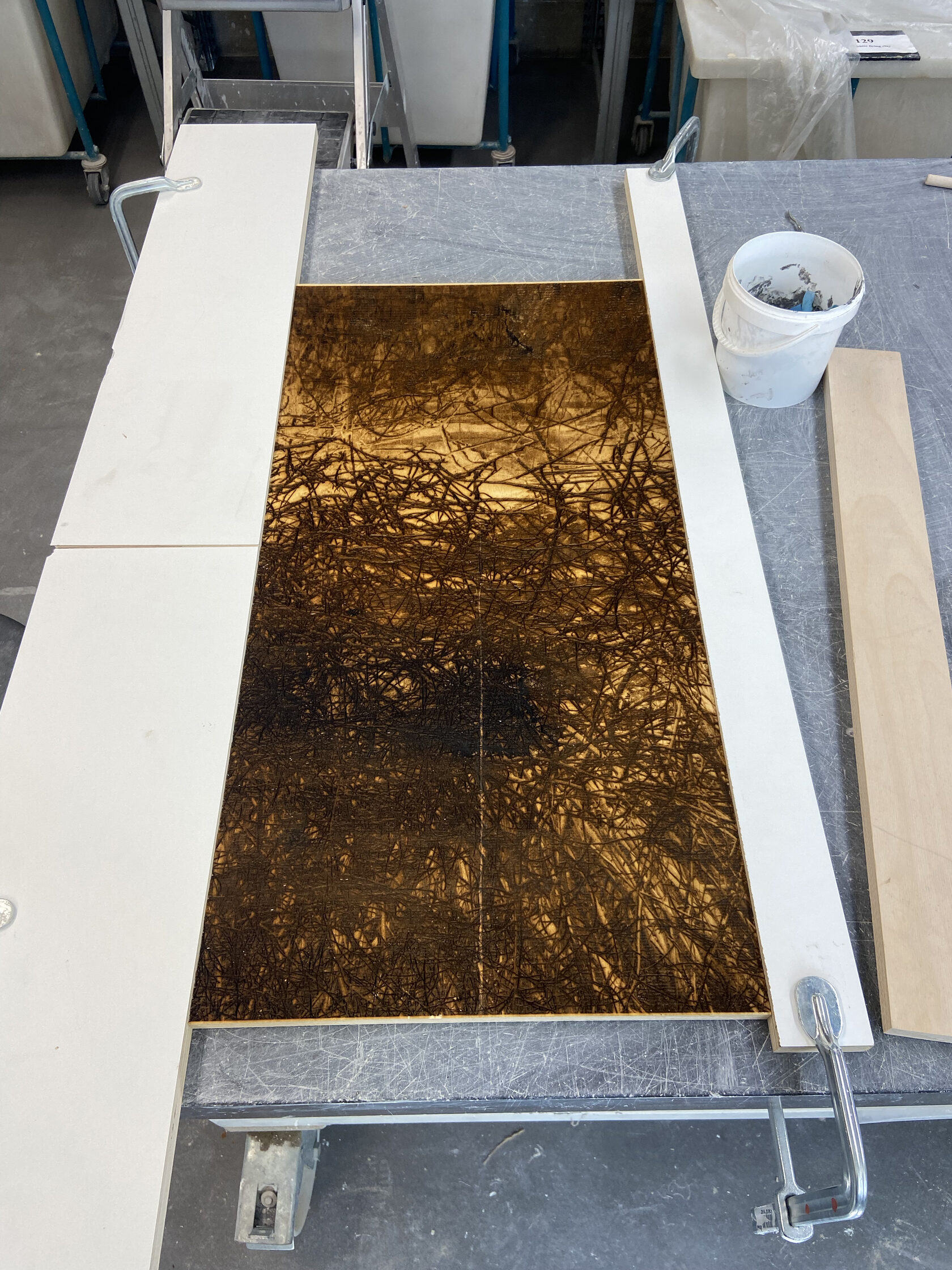

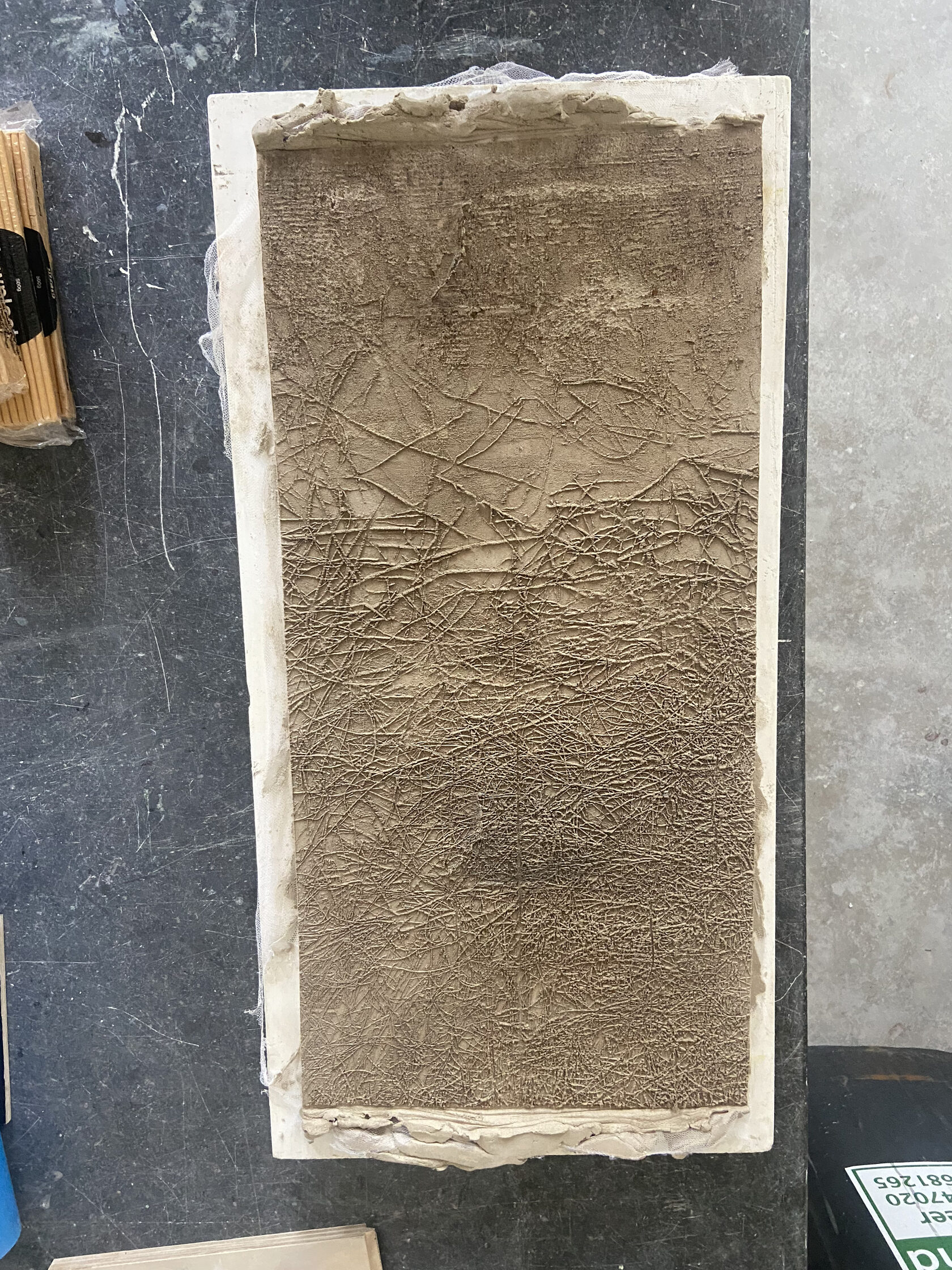

We are multiple: Ceramics

I took photographs from the perspective of the river itself, focusing on the meeting of water and riverbank – sometimes a natural barrier, but more often stone and concrete. On the riverbanks, I found a clay-like substance that I decided to work with, having tested it at attraction terrestre, a local ceramics studio in Arles. Where the Rhône has been subdued by hydraulic and nuclear technology, I wanted to adopt a technical and distant approach to my own way of working. Organic material and mechanical process intertwine here: I laser cut photographs, creates reliefs, presses clay into them, and glazes her ceramic landscapes with clay from the Rhône.

I took photographs from the perspective of the river itself, focusing on the meeting of water and riverbank – sometimes a natural barrier, but more often stone and concrete. On the riverbanks, I found a clay-like substance that I decided to work with, having tested it at attraction terrestre, a local ceramics studio in Arles. Where the Rhône has been subdued by hydraulic and nuclear technology, I wanted to adopt a technical and distant approach to my own way of working. Organic material and mechanical process intertwine here: I laser cut photographs, creates reliefs, presses clay into them, and glazes her ceramic landscapes with clay from the Rhône.

We Exhale – video

The river breathes out. Organic materials which fill the water are slowly broken down through chemical processes, creating carbon dioxide (CO2). What sound does a river make when exhaling? Does this sound change as the river is poisoned, distorting and fading from its natural state?

Throughout the summer of 2022, I followed the river from the Mediterranean to its source in Switzerland, charting its transformations, its journey, and its many voices. A collaboration with sound artist Liz Harris formed a sensitive soundscape from ambient noise combined with field recordings. Together, they created a poetic means to reflect on how a poisoned river might possibly exhale.

The river breathes out. Organic materials which fill the water are slowly broken down through chemical processes, creating carbon dioxide (CO2). What sound does a river make when exhaling? Does this sound change as the river is poisoned, distorting and fading from its natural state?

Throughout the summer of 2022, I followed the river from the Mediterranean to its source in Switzerland, charting its transformations, its journey, and its many voices. A collaboration with sound artist Liz Harris formed a sensitive soundscape from ambient noise combined with field recordings. Together, they created a poetic means to reflect on how a poisoned river might possibly exhale.

Ceramic tests, Rhône clay mixed and fired as glaze

We exhale, 3 panels of 112 x 50 cm, clay with Rhône clay glaze

Where the river meets the sea, still from We exhale The process

"We Exhale", video stills

Listening to the river

"We Exhale", video stills

METHODOLOGY

2/4

Since my interests have focused on landscaped shaped by energy production I’m always sensitive to news, articles, books and other materials related to this subject. Sometimes, a dispute on pollution, the economics of oil and gas, or the philosophical debate on the rights of nature, a news headline piques my interest for a place. My mind lingers for a long time towards a subject, I start to obsess, read books, articles, look up archival materials and maps. Usually this process starts in my studio, and once I feel more equipt (knowing more of the background of a subject), I venture out. But this is sometimes not as easy.

A lot of these places are not open to the public, and I feel it is also part of the process to negotiate with different partners (companies, local government etc) to get access to the locations. For example, it took almost a year to gain the permissions and right certification to travel with companies supplying the offshore industry and to visit a platform on the Northsea. Of Course you can find other ways to visit these places, and not go through official channels, but for me, it is important to meet the people who actually work (and sometimes live) in these places, the inside perspective so to say.

Then the actual work starts. My camera, recording equipment and notebook are my companions when I stay and document these places. They are intensive days, staying and moving through the landscape. All the recorded materials go back to my studio, I watch and rewatch. When possible, I’ll often go back multiple times to the same places, collecting images, meeting people, appreciating the atmosphere and sense of a place.

Through this process a framework starts to emerge for new works, a text, a soundscape, a film or photography based works. Outcomes can be quite surprising!

All the projects are a link within a chain that becomes longer and stronger, reflecting on a wider level on landscape, the fossil fuel industry and our relationship to its history.

A lot of these places are not open to the public, and I feel it is also part of the process to negotiate with different partners (companies, local government etc) to get access to the locations. For example, it took almost a year to gain the permissions and right certification to travel with companies supplying the offshore industry and to visit a platform on the Northsea. Of Course you can find other ways to visit these places, and not go through official channels, but for me, it is important to meet the people who actually work (and sometimes live) in these places, the inside perspective so to say.

Then the actual work starts. My camera, recording equipment and notebook are my companions when I stay and document these places. They are intensive days, staying and moving through the landscape. All the recorded materials go back to my studio, I watch and rewatch. When possible, I’ll often go back multiple times to the same places, collecting images, meeting people, appreciating the atmosphere and sense of a place.

Through this process a framework starts to emerge for new works, a text, a soundscape, a film or photography based works. Outcomes can be quite surprising!

All the projects are a link within a chain that becomes longer and stronger, reflecting on a wider level on landscape, the fossil fuel industry and our relationship to its history.

RECOMMENDED LINKS AND READING

CONFLUENCE, THE NATURE OF TECHNOLOGY AND THE REMAKING OF THE RHÔNE

Sara B. Pritchard

THE PARLEMENT OF THINGS

Bruno Latour

SOLASTALGIA, AN ANTHOLOGY OF EMOTION IN A DISAPPEARING WORLD

EDITED BY PAUL BOGARD. FOREWORD

Glenn Albrecht

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

JG Ballard

THE 'FRENCH CHERNOBYL' THAT HAS POISONED THE RHÔNE'S FISH

CONFLUENCE, THE NATURE OF TECHNOLOGY AND THE REMAKING OF THE RHÔNE

Sara B. Pritchard

THE PARLEMENT OF THINGS

Bruno Latour

SOLASTALGIA, AN ANTHOLOGY OF EMOTION IN A DISAPPEARING WORLD

EDITED BY PAUL BOGARD. FOREWORD

Glenn Albrecht

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

JG Ballard

THE 'FRENCH CHERNOBYL' THAT HAS POISONED THE RHÔNE'S FISH

The artist collecting clay, sound and images along side the river

The artist collecting clay, sound and images along side the river

Ceramic tests, Rhône clay mixed and fired as glaze

Map of the Rhône delta

Clay found on the banks of the river Rhône’, fired and brough back

The process of using molds to make the ceramic plates

"We exhale", 3 panels of 112 x 50 cm, clay with Rhône clay glaze

VIDEO and poem

3/4

WE ARE MULTIPLE WE ARE NEW WE ARE DEAD WE RESURRECT

NOUS SOMMES MULTIPLES NOUS SOMMES NOUVEAUX NOUS SOMMES MORTS NOUS RESSUSCITONS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

A PHANTOM MOVING SOUTH

UN FANTÔME QUI SE DÉPLACE VERS LE SUD

WE SHAPE SEDIMENT STONES SYNTHETICS SOULS

NOUS FAÇONNONS DES SÉDIMENTS DES PIERRES DES PRODUITS SYNTHÉTIQUES DES ÂMES

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE YIELD

NOUS CÉDONS

WE ASSEMBLE

NOUS ASSEMBLONS

FLUOROALCANES RADIONUCLIDES UNINVITED SUBSTANCES COURSING THROUGH

DES FLUOROALCANES DES RADIONUCLÉIDES DES SUBSTANCES INDÉSIRABLES S’ÉCOULANT DANS

HEAVY WATER

L'EAU LOURDE

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE ENABLE POWER ENERGY TIME

NOUS ACTIVONS LA PUISSANCE L'ÉNERGIE LE TEMPS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE ARE BODY WE ARE OBJECT WE ARE ENERGY

NOUS SOMMES CORPS NOUS SOMMES OBJET NOUS SOMMES ÉNERGIES

WE EXHALE

NOUS EXPIRONS

WE PRESERVE RESIDUES OF POWER WEALTH TIME

NOUS CONSERVONS DES RÉSIDUS DE POUVOIR DE RICHESSE DE TEMPS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE EXHALE

NOUS EXPIRONS

WE MOVE DARKNESS

NOUS DÉPLAÇONS L’OBSCURITÉ

WE DISAPPEAR

NOUS DISPARAISSONS

NOUS SOMMES MULTIPLES NOUS SOMMES NOUVEAUX NOUS SOMMES MORTS NOUS RESSUSCITONS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

A PHANTOM MOVING SOUTH

UN FANTÔME QUI SE DÉPLACE VERS LE SUD

WE SHAPE SEDIMENT STONES SYNTHETICS SOULS

NOUS FAÇONNONS DES SÉDIMENTS DES PIERRES DES PRODUITS SYNTHÉTIQUES DES ÂMES

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE YIELD

NOUS CÉDONS

WE ASSEMBLE

NOUS ASSEMBLONS

FLUOROALCANES RADIONUCLIDES UNINVITED SUBSTANCES COURSING THROUGH

DES FLUOROALCANES DES RADIONUCLÉIDES DES SUBSTANCES INDÉSIRABLES S’ÉCOULANT DANS

HEAVY WATER

L'EAU LOURDE

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE ENABLE POWER ENERGY TIME

NOUS ACTIVONS LA PUISSANCE L'ÉNERGIE LE TEMPS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE ARE BODY WE ARE OBJECT WE ARE ENERGY

NOUS SOMMES CORPS NOUS SOMMES OBJET NOUS SOMMES ÉNERGIES

WE EXHALE

NOUS EXPIRONS

WE PRESERVE RESIDUES OF POWER WEALTH TIME

NOUS CONSERVONS DES RÉSIDUS DE POUVOIR DE RICHESSE DE TEMPS

A TRICK

UNE ILLUSION

WE EXHALE

NOUS EXPIRONS

WE MOVE DARKNESS

NOUS DÉPLAÇONS L’OBSCURITÉ

WE DISAPPEAR

NOUS DISPARAISSONS

Duration: 19’30” (Loop)

Format: 4K / 16:9 Colour

Credits

Concept, Direction & Production: Tanja Engelberts

Camera: Tanja Engelberts

Drone: Jonathan Pierredon

Edit: Rento Van Drunen, Tanja Engelberts

Colour Grading: Marcel Ijzerman

Sound Design: Liz Harris

Audio Mix: Walking In Silence Music

Format: 4K / 16:9 Colour

Credits

Concept, Direction & Production: Tanja Engelberts

Camera: Tanja Engelberts

Drone: Jonathan Pierredon

Edit: Rento Van Drunen, Tanja Engelberts

Colour Grading: Marcel Ijzerman

Sound Design: Liz Harris

Audio Mix: Walking In Silence Music

4/4

We Form, 4 panels of 42 x 100 cm, ceramic glazed with Rhone river clay

We Exhale, video, 19’28” (loop), 4K / 16:9, color

2023

We Exhale, video, 19’28” (loop), 4K / 16:9, color

2023

installation images