A collection of IMAGES ABOUT A COLLECTION OF IMAGES

ABOUT THE RESEARCH AND THE PROJECT

1/2

The project is situated in the continuation of my research and the questions I've already opened up about the back-and-forth movement of art objects that took place between the Algerian and French states during colonial occupation and the years following independence. More precisely, it reflects on a specific historical episode in the transition to Algerian independence, which crystallizes many of the issues I'm seeking to address in my work. As part of my research, I came across Andrew Bellasari's article1 on a military transport undertaken by France on the morning of May 14, 1962:

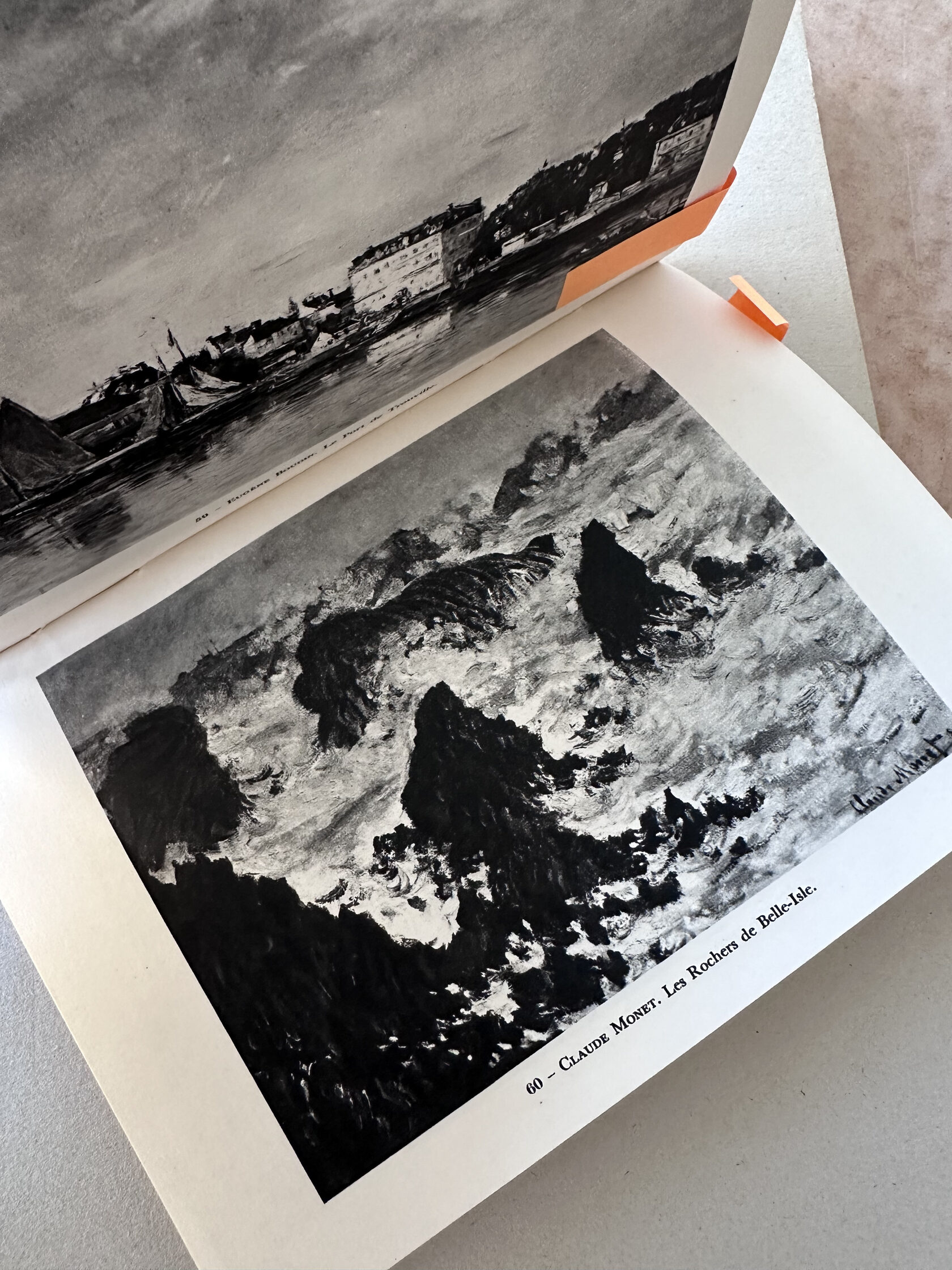

"Two months before Algerian independence, a unit of French gendarmes escorted eleven wooden crates from a military quay in Algiers and placed them on a cargo ship bound for Marseille. The crates were then loaded onto a train bound for Paris, where they arrived at the Louvre on May 23. The museum's curators were then able to examine their contents and discovered over 300 works of art, including works by such famous French artists as Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, Pissarro, Degas, Courbet and Delacroix. According to the inventory drawn up by the conservation team, the crates contained 188 paintings and 136 drawings, sketches and charcoals. The works of art, however, no longer belonged to France. By virtue of the Evian Accords, they had become the official property of the future Algerian state, which would reclaim them, finally, in 1969".

"Two months before Algerian independence, a unit of French gendarmes escorted eleven wooden crates from a military quay in Algiers and placed them on a cargo ship bound for Marseille. The crates were then loaded onto a train bound for Paris, where they arrived at the Louvre on May 23. The museum's curators were then able to examine their contents and discovered over 300 works of art, including works by such famous French artists as Monet, Renoir, Gauguin, Pissarro, Degas, Courbet and Delacroix. According to the inventory drawn up by the conservation team, the crates contained 188 paintings and 136 drawings, sketches and charcoals. The works of art, however, no longer belonged to France. By virtue of the Evian Accords, they had become the official property of the future Algerian state, which would reclaim them, finally, in 1969".

Research image © Camille Kaiser, 2023

This article reflects not only on the French decision to act in violation of the Evian Accords, but also the subsequent negotiations between France and Algeria and examines the cultural complexities of this post-colonial restitution.

If I wish to look at these artworks, it is because they are, for me, the mute witnesses of a complex administrative, diplomatic and legal history, and a facet of the protean mirror of this moment of transition towards independence. They were caught up in colonial/decolonial dynamics and flows, and bear knots to untangle, the traces to unearth. What does it mean when works of art produced by some of France's most emblematic artists - Monet, Delacroix, Courbet - become the cultural property of a former colony? What happens when a former colony demands the repatriation of emblematic works of art from the former colonizer, believing them to be part of the nation's cultural heritage?

If I wish to look at these artworks, it is because they are, for me, the mute witnesses of a complex administrative, diplomatic and legal history, and a facet of the protean mirror of this moment of transition towards independence. They were caught up in colonial/decolonial dynamics and flows, and bear knots to untangle, the traces to unearth. What does it mean when works of art produced by some of France's most emblematic artists - Monet, Delacroix, Courbet - become the cultural property of a former colony? What happens when a former colony demands the repatriation of emblematic works of art from the former colonizer, believing them to be part of the nation's cultural heritage?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Art of Decolonization: The Battle for Algeria’s French Art, 1962–70, Andrew Bellisari, The Journal of Contemporary History, 2017.

This ongoing research explores the history of this collection, questioning how Algeria came to claim stewardship of a vast collection of artworks emblematic of the culture, history and religion of the former French colonizer. This story nuances the generally narrated tale of European empires seizing "indigenous" artifacts and artworks in the name of knowledge, power and prestige. Here, it is the colonizer's artistic heritage that is at stake, recasting the notion of post-colonial restitution. This consideration invites to reassess the process of decolonization as one marked by mutual reclamation and cultural negotiation, rather than understanding it primarily through the prism of rupture and trauma. It enables to read well beyond the dividing line of independence, beyond the simple "before" and "after" partition of colonial and post-colonial history, and to examine how the process of decolonization was operated between local actors on both sides of the Mediterranean.

What I am most interested in this story is that, rather than seeking to erase the cultural imprint of the former colonizer, the Algerians - or at least those acting in an official capacity - accepted the cultural heritage bequeathed to them through diplomatic tactics and negotiated the restitution of their state's legitimate assets. A "spoils of war" perhaps, but a national treasure nonetheless. Highlighting such a reappraisal can serve as a counterweight to the totalizing qualifications often associated with the drama of colonial dismantlement, particularly in the Algerian case, and allows to see that instead of producing two distinct nation-states, amputated or restored, with two distinct histories, the process of decolonization redefined the relationships between them, maintaining interconnections more often than it broke them.

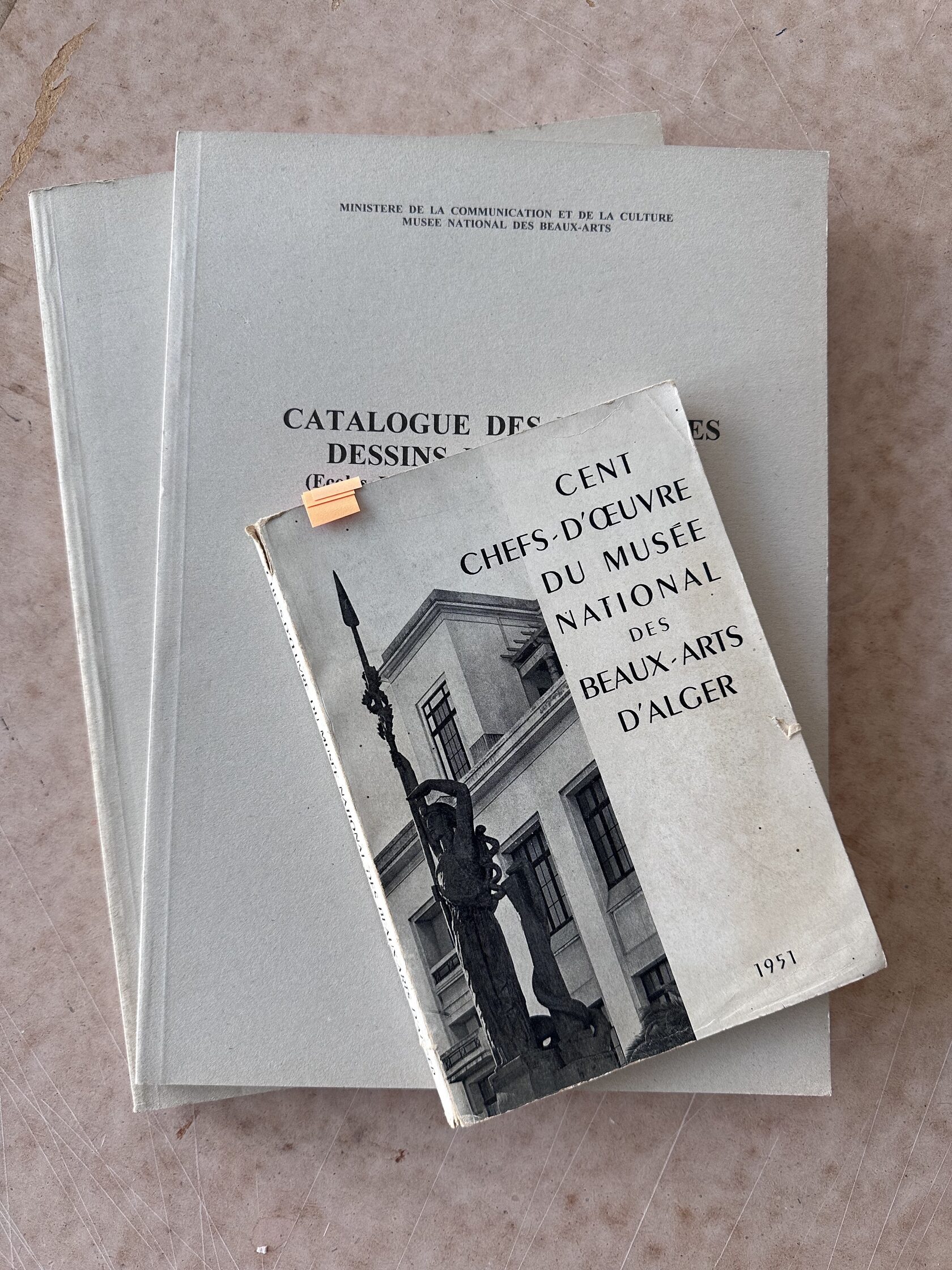

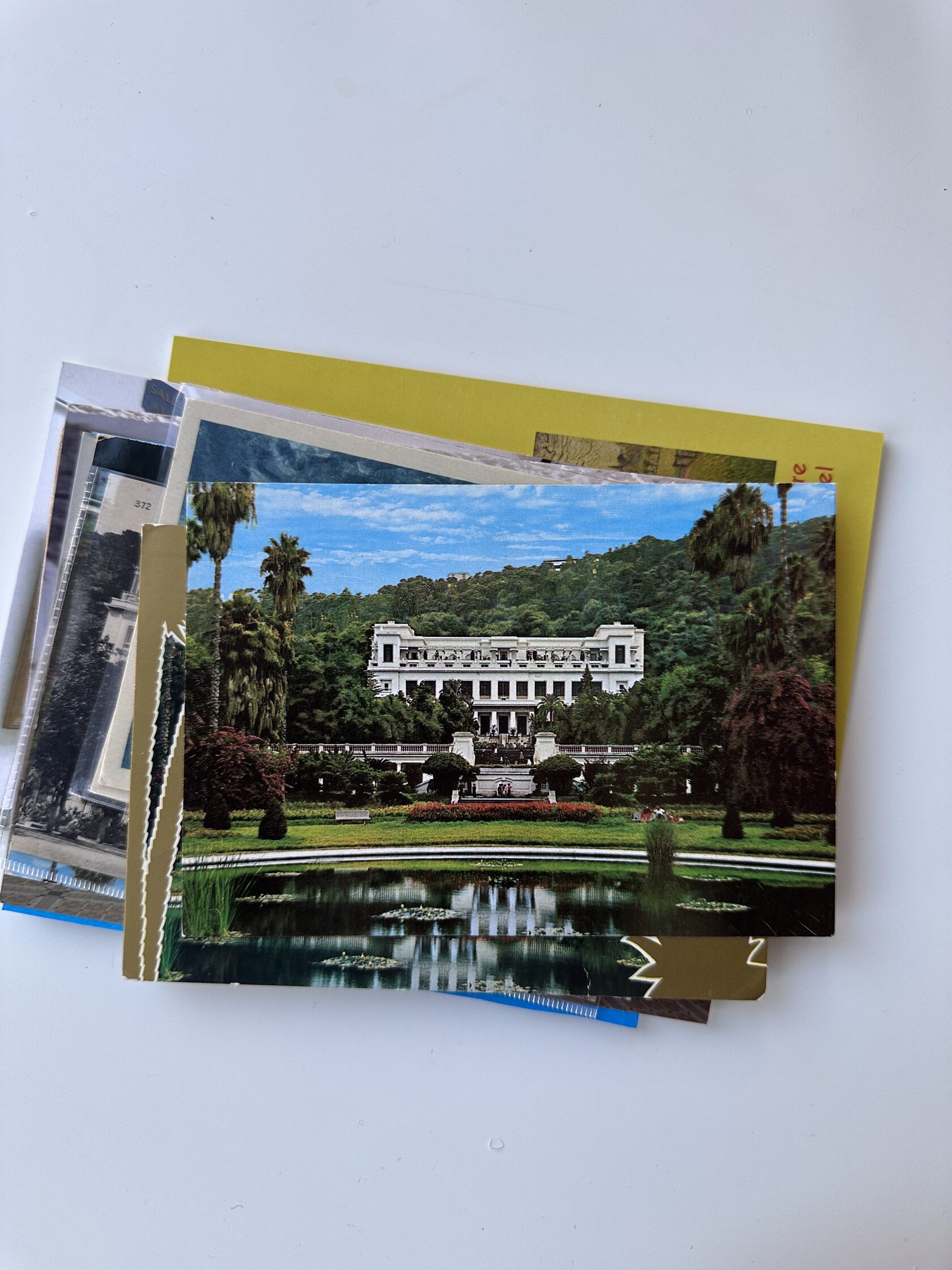

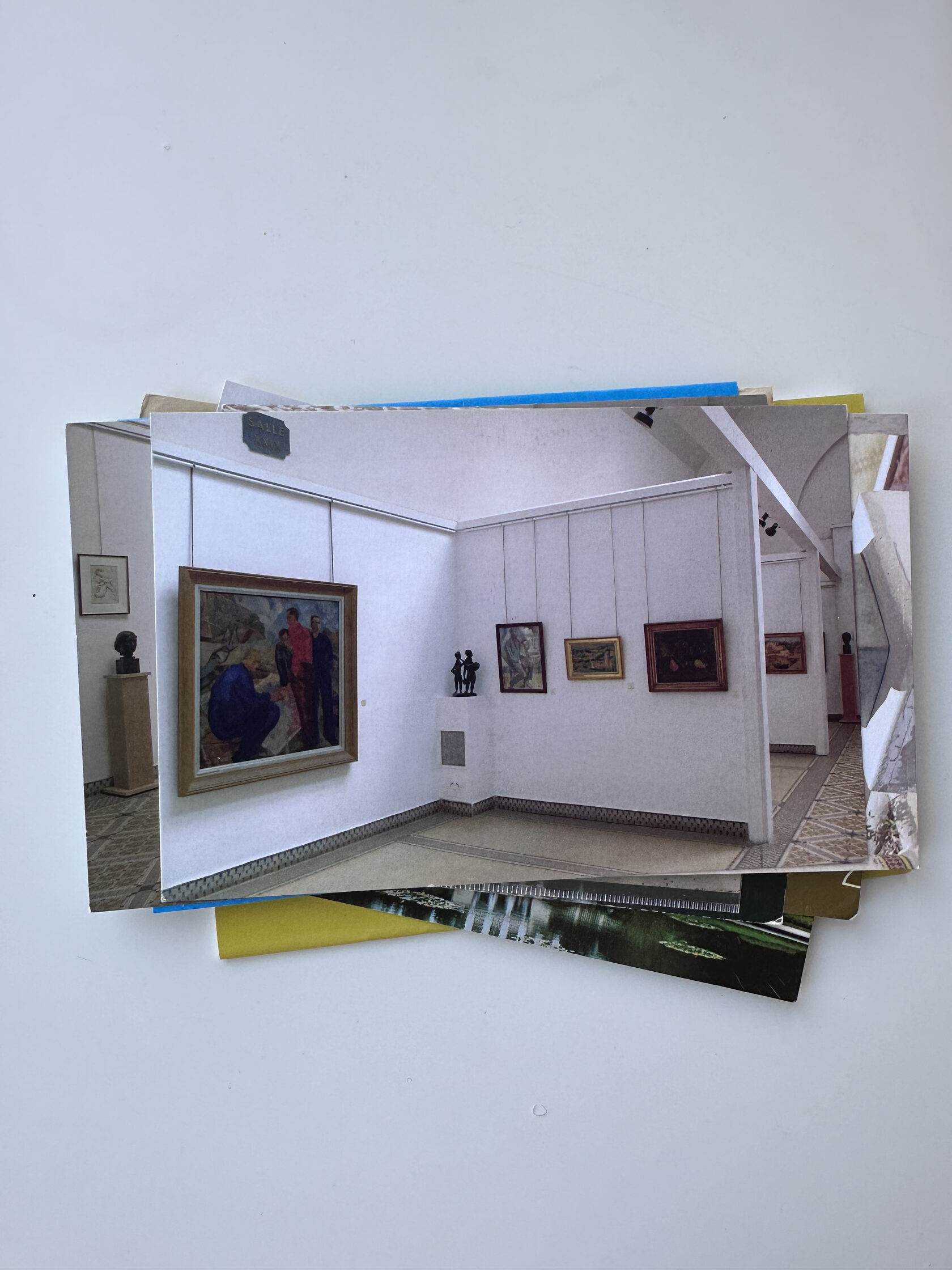

In May 2023, I visited the Musée national des Beaux-Arts in Algiers for the first time. Inspired by the curation of both the African and European art collections, the installation a collection of images about a collection of images reflects on the history of these museum displays. The layout presents a new series of images created from photographs taken during my visit, in addition to archival documents linked to the museum’s history, in an attempt to map the traces and provenance of artworks by collecting what images I can find and create.

What I am most interested in this story is that, rather than seeking to erase the cultural imprint of the former colonizer, the Algerians - or at least those acting in an official capacity - accepted the cultural heritage bequeathed to them through diplomatic tactics and negotiated the restitution of their state's legitimate assets. A "spoils of war" perhaps, but a national treasure nonetheless. Highlighting such a reappraisal can serve as a counterweight to the totalizing qualifications often associated with the drama of colonial dismantlement, particularly in the Algerian case, and allows to see that instead of producing two distinct nation-states, amputated or restored, with two distinct histories, the process of decolonization redefined the relationships between them, maintaining interconnections more often than it broke them.

In May 2023, I visited the Musée national des Beaux-Arts in Algiers for the first time. Inspired by the curation of both the African and European art collections, the installation a collection of images about a collection of images reflects on the history of these museum displays. The layout presents a new series of images created from photographs taken during my visit, in addition to archival documents linked to the museum’s history, in an attempt to map the traces and provenance of artworks by collecting what images I can find and create.

2/2

Installation. Wooden plinths, glass, photographic prints (various sizes), archival postcards (various sizes), golden weights. 2023

installation images